From cluttered dressing tables to morning-after debris, Emma Elizabeth Tillman, photographer and wife of Father John Misty, shares an insight to her world

“I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear,” wrote Joan Didion in her article Why I Write, published in The New York Times in 1976. This oft-quoted essay explains Didion’s ability to recall the “exact rancidity of the butter in the City of San Francisco’s dining car” rather than one iota of the 10,000 word thesis on Paradise Lost that she had taken that train, every friday for an entire summer, to write. Such a desire to attentively record, review and extol the overlooked minutiae of daily life comes to mind when regarding the photographic work of artist Emma Elizabeth Tillman.

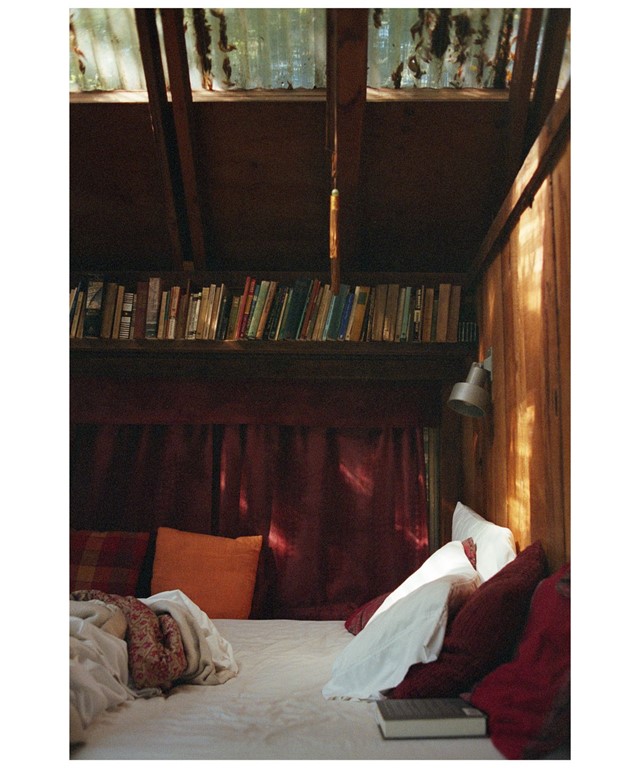

“I take pictures almost every day. I have to do it. It’s like writing, I write in a diary every day too,” Tillman explains, as she talks me through her new, and first, photo book Disco Ball Soul. “I’m so private as a person that it helps me to figure things out.” As such, her photographs – an eclectic gathering of textural swatches – act as a personal journal, honing in on peripheral moments of beauty: a cigarette held loosely by her husband (musician Father John Misty); crinkled bedsheets; watermelon rinds discarded in a sink; body parts submerged in water; half-open doors; a party debris-littered balcony; tiny corners of her Laurel Canyon home; hotel room, after hotel room, after hotel room. Soft and intimate depictions of friends fill the tome, as do many of her husband Josh, to whom the book is dedicated. Each vignette reveals a fragment of a beautiful life, or, according to Tillman, a life made beautiful by the act of capturing it.

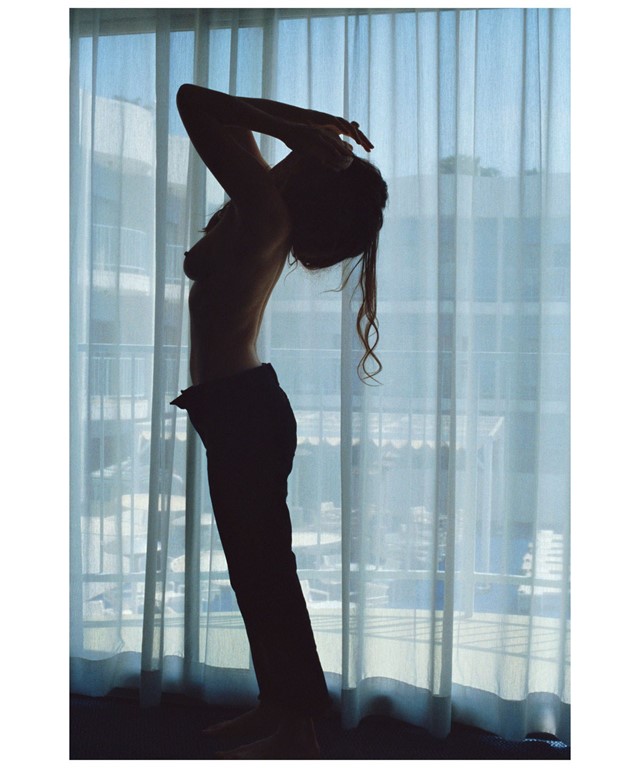

Taking her photographs entirely “by feel” – no light metre, no tripod, no lighting, no backdrop – they are everyday pictures in a sense. You feel as if you could have seen them before, that you will see them again, that they could be a fragment of your own life. They are enduring. But they are tied inextricably to Tillman’s world. The artist spent two years hand-printing and compiling ten years’ worth of images into scrapbooks, scribbling notes and memories from each day along their masking-taped hinges. Those same notations line the walls of her debut Whitechapel exhibition, drawing each visitor into the folds of that world. Her self portraits, often nudes, are as much a self-seduction as an exposition: intensely personal, though somehow universal. Each study is made in a bid to understand Tillman’s own life and in so doing, she offers a lens through which to see your own. Here, Tillmans talks us through her work, and life, in progress.

On elevating the everyday...

“I am very free in my style but I am very intentional as an artist about what I want to capture: it’s all in the quotidian. It’s elevating the quotidian. While I use photographs to examine my own life, I also feel like those pictures make people feel like their own lives are beautiful, in a way. Because they’re all about something everyone can relate to, they’re like self portraits: there’s pictures of me rearranging my underwear drawer, there’s friends in swimming pools, it’s all very quotidian things that I’m interested in. But I like finding that moment of mystery – I know exactly when I’ve seen it. It’s a kind of eternal feeling.”

On her Encyclopedia Britannica house in Laurel Canyon…

“They call them the Encyclopedia Britannica houses because in the 20s, in Los Angeles, if you bought an entire set of Encyclopedia Britannicas, you were given a plot of land in the Hollywood Hills, for free. And people built these houses as weekend hunting cabins because people used to hunt in the Hollywood Hills. Isn’t that incredible? There’s not many of them, there are probably about 15, in the hills. And they have beautiful river-rock fireplaces, it’s all wood-paneled with super high-beamed ceilings. We live down a dead end road and one of our neighbours owns an entire mountain side. On the other side the land is protected as a wildlife quarter so we have deer and coyotes. It’s so beautiful, it’s such a special place.”

On how taking photos helps you see more…

“I actually think photography can become a way of life. If you look carefully, you just see beauty – things become more beautiful. In a way it’s holding onto things. But I was just reading this interview with Nan Goldin, a pretty famous quote of hers: ‘I used to think that I could never lose anyone if I photographed them enough. In fact, my pictures show me how much I’ve lost.’ And it’s true, you can never get that moment back but really, these are a vain attempt at trying.”

On her fraught relationship with self-portraits...

“I just set them up on a table and use a self-timer. There’s never anyone in the room. I actually feel like I photograph terribly and I’m the only person that can photograph me as myself. It’s something I feel really private about. But then I print them, which is such a contradiction! I suppose I like attention but only on my own terms. I don’t like the idea of having attention that was highly controlled. It’s a way of showing myself to myself. Only through these pictures do I get to really see what I actually look like. Because it’s so skewed when you look in a mirror.”

Disco Ball Soul runs until August 30, 2017 at Gallery 46, Whitechapel and is published by Dilletante Paper.