Discover the story behind Ide Collar, the work that set the tone for Outerbridge’s revolutionary style of image-making

Last month marked the release of a trilogy of photo books by Taschen, each dedicated to an American 20th-century photographic “master of light”: Man Ray, Edward Weston and Paul Outerbridge. Here, in the last of our three-part dedicated series, we explore the story behind an enduring image from the third: Ide Collar by Paul Outerbridge.

Paul Outerbridge’s contributions to photography are immeasurable. At the height of his professional career, the late image-maker was New York’s highest-paid commercial photographer, while as an artist, he was a revered equal in a circle of innovators including Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Pablo Picasso and Constantin Brancusi for his able translation of avant-garde ideology onto film. He was able to render the ordinary extraordinary like no other, courtesy of his remarkable technical prowess, clever use of lighting, and exquisite eye for composition, texture and tone. In the 1930s, he became a key pioneer of colour photography, painstakingly developing the tri-colour-carbro printing process – a complex and costly method of producing bold colour prints from black and white negatives – and thereafter shocked the world with his explicit depictions of nude women in vibrant, fleshy hues.

Outerbridge was born to a wealthy New York surgeon in 1896. His parents envisaged an academic path for their son, but from a young age Outerbridge’s interests were firmly rooted in art; he worked as an illustrator and designed sets for amateur theatre productions while still in his teens, and began experimenting with photography in 1917, while serving in the US army. In 1921 he enrolled in Clarence White’s School of Photography, where he developed many of his most recognisable stylistic trademarks. He wrote during his studies of the “real incentive” he found in his medium, going on to set up a studio in his family home where he would spend hours in between classes capturing everyday objects like eggs and lightbulbs with a unique precision, refinement and geometry that rendered them quasi-abstract. His aim, he said, was “to interpret the beauty existing in the simplest and humblest of objects” by creating “artificial paradises” in which they could exist. To achieve this, he would sketch out every composition in advance, leaving no elements up to chance – from how the scene should be lit to the interplay of shapes, patterns and tones.

Just one year after starting at Clarence White’s, Outerbridge had captured the attention of esteemed fashion publications Vogue and Vanity Fair, as well as various New York ad agencies, who recognised in the young photographer an exceptional talent for original and artful still lifes. His first ever advertising assignment, for New York Gentleman’s collar purveyors Ide & Company, remains one of his most iconic images for its quintessential Outerbridge-ian brilliance. Taken in 1922 and published in Vanity Fair a year later, it depicts a starched white collar, lying in a delicately curling “c” shape on a black and white checkerboard. The geometric contrast between the collar’s curve and the board’s squares, in addition to the surrealist proportions, which make the collar appear bigger in relation to its background, elevate what could have easily been a formulaic accessory advertisement to a lyrical work of modernist art. As Elaine Dines-Cox notes in an essay for the Taschen tome, “the balanced perfection of Outerbridge’s composition corresponds to the Renaissance theoretician Leon Battista Alberti’s definition of formal beauty: no element may be added or subtracted without disturbing the harmonious congruity of the whole” – a tenet that Outerbridge resolutely stuck to.

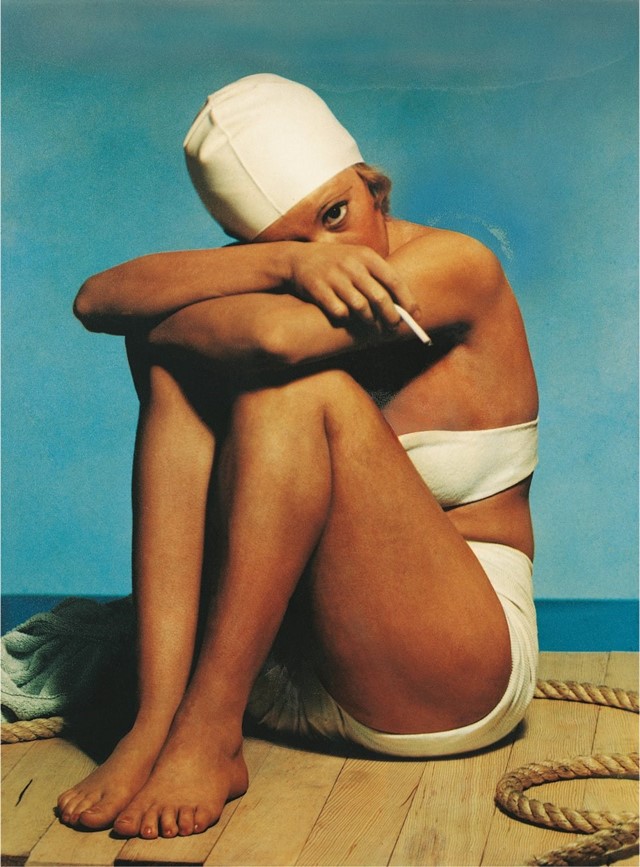

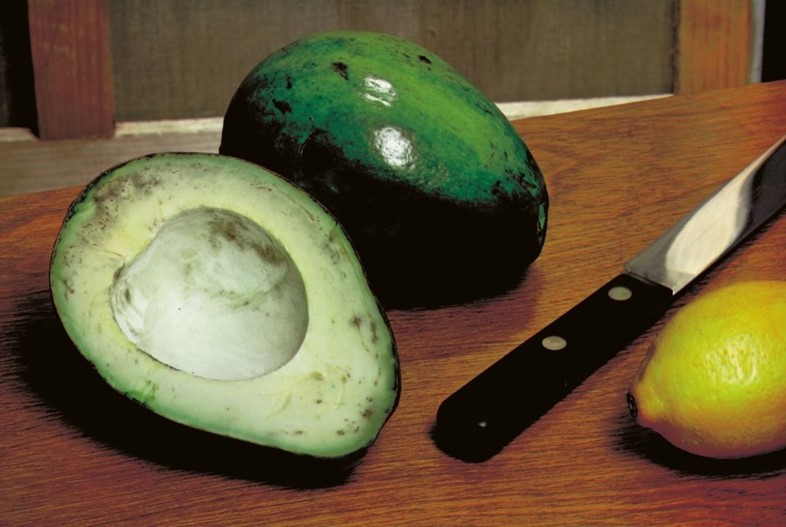

It was this image that Marcel Duchamp tore from his copy of Vanity Fair, prior to meeting Outerbridge, and tacked onto his studio wall, declaring it a paragon of the “ready-made”. “Perceiving it as a found object transformed into art through the imagination of the artist, Duchamp identified [the work] as additional evidence for the redefinition of objects,” Dines-Cox explains. Ide Collar was still hanging on Duchamp’s wall in 1925, when Outerbridge moved to Paris for a influential sojourn in the city that saw him swiftly befriended by the Dada pioneer and his fellow visionaries. Later, of course, Outbridge’s self-reinvention as a master of colour would see him push advertising into new, unexplored realms, as well as enabling him to imbue his works with a delectable richness, whether portraying plump green avocadoes or theatrically masked nudes. But Ide Collar remains one of his most important works, as one of the earliest indications of what Dines-Cox terms his innate understanding of “how desire for beauty in art, as in life, could translate into modernist, elegant and alluring everyday forms, things of beauty that promised pleasure”.

Paul Outerbridge, edited by Manfred Heiting, is available now, published by Taschen.