Exhausted by contemporary culture’s denigration of photography, Miles Aldridge sought out Gilbert & George, Harland Miller and Maurizio Cattelan to shake things up

The era of the smartphone has taken its toll on photography. Our consumption of images in the modern era feels somehow facile and fleeting, every isolated human inundated with an endless stream of low-grade visual stimuli via the palm of their hand. Or at least, this was the thought at the forefront of Miles Aldridge’s mind when he embarked on his latest series of photographic prints, which explore various image-making techniques in a series of collaborations with the most iconic of contemporary artists. Aldridge is one of a handful of photographers working today whose work stands apart as instantly recognisable – his penchant for exploring the intangible commonalities of existence through frozen existential moments is utterly unique.

The collaborative series After at the Lyndsey Ingram Gallery, however, marks new territory, and a battle to reclaim the singular power of the image. Aldridge’s investigative collaborations with the artists Gilbert & George, Harland Miller and Maurizio Cattelan not only explore the vagaries of the relationship between eye of the lens and the artists themselves, but also champion idiosyncratic analogue photographic techniques that deal in tone and the impact of colour. Here, the fashion photographer gives AnOther the inside track on each unique collaboration, and explains why we tend to end up doing the things in life that we are second best at.

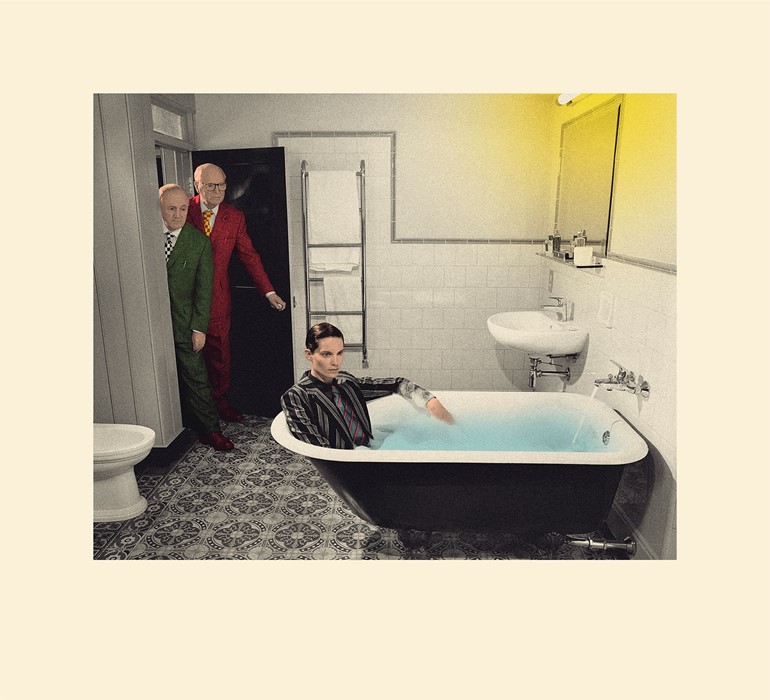

On Gilbert & George...

“The Gilbert & George works are a series of photogravures, which is a kind of ancient form of reproducing coloured photographic images used by Muybridge. I’ve played very much with this idea of Victorian postcards, but the nod to Victoriana has been kind of ‘pop-arted’ by blocking them in pop colours, so they are simultaneously historic and contemporary, which is where I always like to place my work. The series was shot over one day at their home, 12 Fournier Street. I had photographed them before, and the thing that had really stayed with me was that when I knocked on the door, there was a sense that behind the door, a lot was being arranged – I could hear things moving around. The door opened very suddenly and George stepped out with a hand stretched out towards me, and just down the corridor I could see Gilbert, positioned rather like a sort of stuffed bear. It was all perfectly organised, and, of course, after I spent more time with them, I realised that everything they did had this incredible level of organisation and theatricality.

“Having had that experience of the being the visitor, I kind of posed a question to myself about who could be arriving in this theatre, and that’s when I got the idea of ‘Georgina’ – an androgyne who is kind of one of them. It led me straight away to images of Hitchcock’s The Lodger, but I wanted a woman as a man rather than another man with the boys. The excitement I’ve found working with these historical photographic media that I’ve been revisiting, like the photogravure, is about reclaiming the photographic image, the photographic print – I need more at the moment, I need a different texture, because photography has been so flogged to death in the age of the iPhone, and kind of ruined for me.”

On Harland Miller...

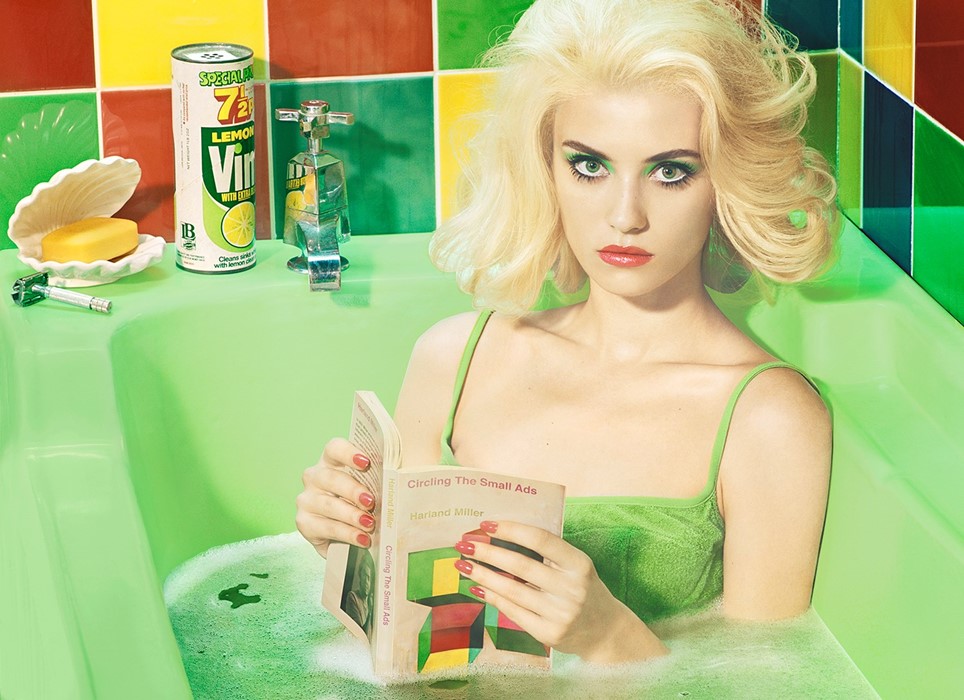

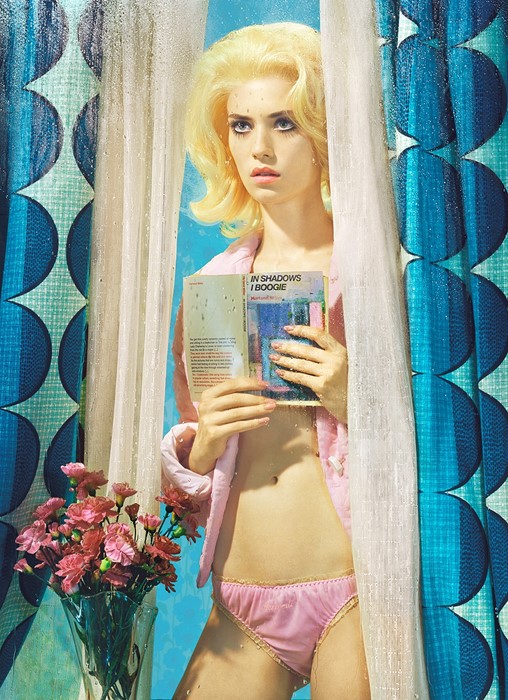

“I’ve known Harland most of my adult life. When I first met him he was trying to be a writer and I was trying to be a filmmaker – we were both sort of aiming at different things, and there’s that lovely quote from Flaubert that comes to mind, about all of us ending up doing the things in life we’re second best at. This summer, I was at his show at White Cube where he was presenting his second album, if you like – he had rid himself of the Penguin motif and was presenting a series of 60s psychology paperbacks in the spirit of RD Laing, full of these weird geometric shapes. I immediately thought: ‘How can I do something? How can I respond?’ The idea came to me to return the books to being books and create a handful of images of a woman reading them in various cinematic scenarios.

“Harland and I have lots of shared cultural references from growing up in the 70s, so that was the the universe I felt I could create – I thought a lot about Morrissey and the aesthetic of the kitchen sink drama. I had the Sunday supplement printing technique in mind. I felt the dot being screen-printed would give it kind of an art twist. We did an insane amount of testing until we got to a point where I was happy with the quality that I was getting from the screen-print. I wanted them to have a feeling of the CMYK dot being really coarse, but in order to really explain that I felt I needed to have areas that were flatly printed too. Each of them has, for example, an area printed in a dead flat ink, so you’ve got this contrast. Because of the variances in the screen-printing, they’re all unique. One of the reasons I’ve done what I’ve done with this body of work is a reaction. It’s about how I feel as a photographer working in this world of mass consumption.”

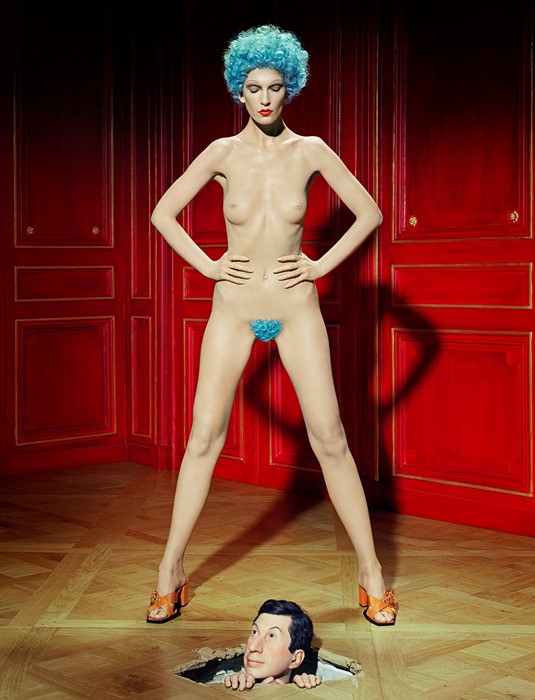

On Maurizio Cattelan...

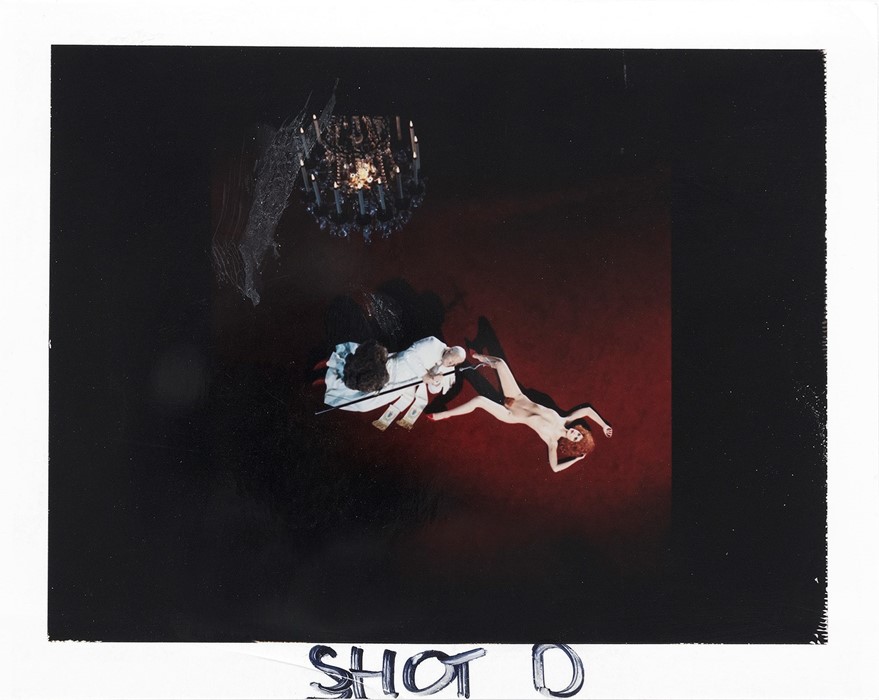

“These images were created last December. I had been in touch with Maurizio in a very casual way, by email, because one of the stylists I was working with told me that she was doing this project for Toilet Paper and I was like, ‘Wow, I love Toilet Paper – tell them that I love them’. I got an email back from Maurizio saying, ‘Oh, by the way, we love your photography too, thanks for the message’. I got in touch to thank him, and then, out of the blue, he sent me a message saying he had an exhibition at La Monnaie in Paris, and that he thought it might be a really good backdrop for some photos. I like the idea that Maurizio is very contemporary and I wanted him to be kind of confronted in a slightly angry and questioning way by the spirits of the museum. I came up with the idea of these women who were expressive of the classical era of the museum, because the museum is kind of baroque, and then a brilliant Jean-Luc Godard short I had seen as a young man clicked in my mind.

“In the film Aria Godard had placed invisible Valkyries in a gymnasium with carving knives, strolling around men working out, kind of brushing knives across their bodies, staring at them, confronting them. That seemed to make total sense to me as to what I wanted to do exploring this kind of vengeful, fearsome and very scary figure. I turned up at the museum up with this model, the team, hair, make-up, assistants, equipment, cameras, film, and so on, and I must say, we didn’t really waste much time – we spent the whole night in the museum taking pictures together. In my work, I have to have a plan, but I think probably one of my talents is that I’m able for that plan to evolve at the drop of a hat – for example the idea of adding the coloured hair to the women came to us on the night, and that has got nothing to do with classical art, it has more to do with Allen Jones. I’m very fluid at stepping sideways, and seeing things from another angle. I think that has probably kept me true to myself.”

Miles Aldridge (after): Projects with Harland Miller, Maurizio Cattelan, Gilbert & George is at Lyndsey Ingram Gallery, London, until January 5, 2018.