As a new exhibition opens at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Holly Black sits down with the contemporary art icon to talk about Louis Vuitton and philosophy

To call Japanese contemporary artist Takashi Murakami prolific is a gross understatement. He admits to taking his cue from the pop sensibilities of Andy Warhol and has always combined commercial enterprise with fine art practice. He has disseminated his various motifs (such as flowers, skulls and a Mickey Mouse-esque character called Mr DOB) across the world under his postmodern term ‘superflat’, which combines elements of Japanese anime, ukiyo-e (traditional Japanese prints) and a massive dose of kawaii. His joyous, colourful, graphic images have permeated every level of pop culture via collaborations with music stars such as Kanye West and Pharrell Williams and huge brands including Supreme, Vans and – most famously – Louis Vuitton. He designed the rainbow monogram that practically eclipsed the original brown version and emblazoned his characters all over handbags and other accessories. Now, in the Parisian suburbs, the Fondation Louis Vuitton has dedicated an entire floor to his work, in the exhibition Au Diapason du Monde (In Tune with the World), which showcases highlights from the company’s significant art collection.

Considering the artist’s history with the commercial side of this brand and his own opinions on the benefits of transparently marrying art and business (he also operates a production company called Kaikai Ki Ki) one must wonder, how does he differentiate between the two? “Collaboration is part of the design thing,” he explains, in a slow, meditative tone. “An art piece is without a contract; it has much more freedom. So, when I was doing my Multicolore collaboration I had questions for Marc Jacobs and his team. My own pieces are completely different. I don’t think the design work links to the fact that Bernard Arnault has actually bought my pieces over the last ten years. It looks like the same name: Louis Vuitton and people do wonder, but this is completely different. It was quite surprising because everything they chose was very big. It really fills these galleries.”

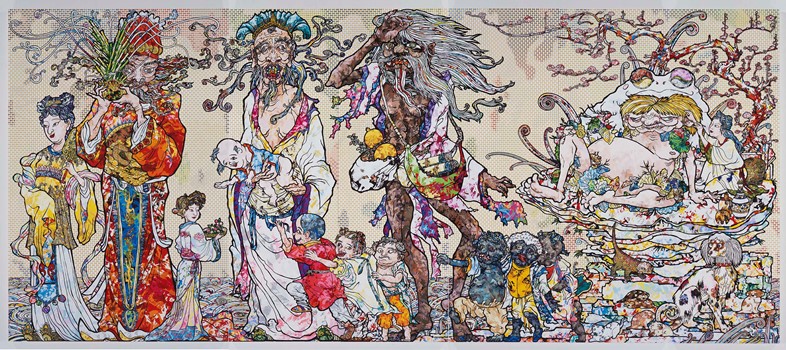

The fact is indisputable. His enormous canvases and sculptures still have a huge amount of room to breathe in the large spaces carved out in this Frank Gehry-designed museum. The works bounce between ecstatic, grinning blooms and more sinister creatures. The most macabre sensibilities are found in The Octopus Eats its Own Leg, a narrative piece that features figures from Chinese and Japanese philosophy and a particularly menacing tentacle sculpture that is covered in graffiti. It is informed by the horrifying consequences of the 2011 tsunami that caused devastation in Japan’s Tōhoku region.

“The tsunami made me think about things. In Japan there is no one religion. The biggest population is the Shinto way, where you believe in the natural. During the tsunami a lot of shrines were broken, meaning people had to pray to nature: ‘Please save me; why are you so angry with us?’ It has a lot to do with volcanos in Japan. You can go to the hot springs because the whole land is volcanic! It means that there are always earthquakes, tsunamis and typhoons. Natural disasters happen quite often, and that’s why Japanese religion has a lot of different gods; a god for the doctor, or for the window, for example. I realised, after the tsunami, that this is why we have so many different images, which all come from nature. My family was in a cult religion and I hated it. I followed the family way, going and praying, but when I went to high school I quit. I thought ‘I hate religion’, but after the tsunami, I totally understood it. It changed my style of thinking.”

Murakami has also had issues of acceptance within his native country. While he has enjoyed enormous success internationally and developed something of a cult following among western Sneakerheads, he is derided among the Otaku (geek) culture that thrives in Japan. Surely there must be a link between these two obsessive communities? “This is a super question, a big question,” he says, “because Japanese geeks hate me. But when I go to a Sneakerhead event, like ComplexCon, the outfits [that the attendees wear] look like Japanese geeks. These people love me – why? I don’t know!” The sartorial similarities do seem evident, but Murakami thinks that perhaps the reason these cultures react to him in such different ways is because they are somehow opposing forces.

He muses that Sneakerheads have some roots in Japan, while Otaku stems from an interest in western culture. So, is there some bitterness in the fact that Murakami has had so much success abroad? He certainly thinks so. “They want to hate me, and I understand it, because their subculture stems from a western concept. [With me] their starting point is crushed.” It seems then, that the close relationship between the artist’s practice and this community is the true sticking point. However, Murakami also has another idea altogether, which harks back to his renewed interest in belief systems: “Otaku do not believe in left or right wing [politics], they are right down the middle. They cannot believe in anything, so that is why they love this subculture. It means they can escape from reality.”

Au Diapason du Monde (In Tune with the World) is at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, until August 27, 2018.