Aperture’s new book is an ode to the irresistible allure of the garden to image-makers the world over

Is there anything that calls out to be photographed quite like a garden, and the flora that grows in it? Even William Henry Fox Talbot, the pioneer of the earliest experiments investigating the capacity of light-sensitive silver salts to record images, opted first to capture the plant species he found around him. When Talbot went on establish the earliest popular techniques for using negatives to create positive prints, he refused to take credit for their composition, insisting instead that they were made “by Nature’s hand”. (How modest.)

So explains Jamie M. Allen, the associate curator at George Eastman Museum and the curator behind In the Garden, a 2015 exhibition charting the evolution of horticulture in photography over the centuries that followed Talbot’s early work. Happily, the exhibition has now been expanded and immortalised with the help of Sarah Anne McNear, in a spectacular new Aperture-published book.

The Photographer in the Garden traces this most satisfying of subjects through early 19th-century cyanotypes (courtesy of Anna Atkins), social and personal domestic documentary (Larry Sultan), still life compositions (Wolfgang Tillmans), seductive, curling close-up detail shots (Karl Blossfeldt) and powerfully erotic photography (Nobuyoshi Araki), to form a comprehensive (though there’s plenty more they could have included, McNear insists) and utterly compelling testament to the visual power of outside spaces. Here are ten of the book’s finest figures.

1. Sheron Rupp, Trudy in Annie’s Sunflower Maze, Amherst, MA, 2000

“I love this picture because it’s so mysterious,” McNear explains over the phone, of Sheron Rupp’s vivid photograph Trudy in Annie’s Sunflower Maze. “We don’t know where the sunflower maze is – [Rupp] doesn’t actually give us an overview of the maze itself – but we do see this woman as being sandwiched by these gigantic sunflowers and their hanging heads. So this is in our ‘seasons’ chapter – it is a late summer, early fall picture, because the sunflowers are all leaning over and their petals are dried up. And I think it’s of course a meditation on age; this woman is walking into this unknown, surrounded by these towering sunflowers who are hanging their heads almost in mourning.”

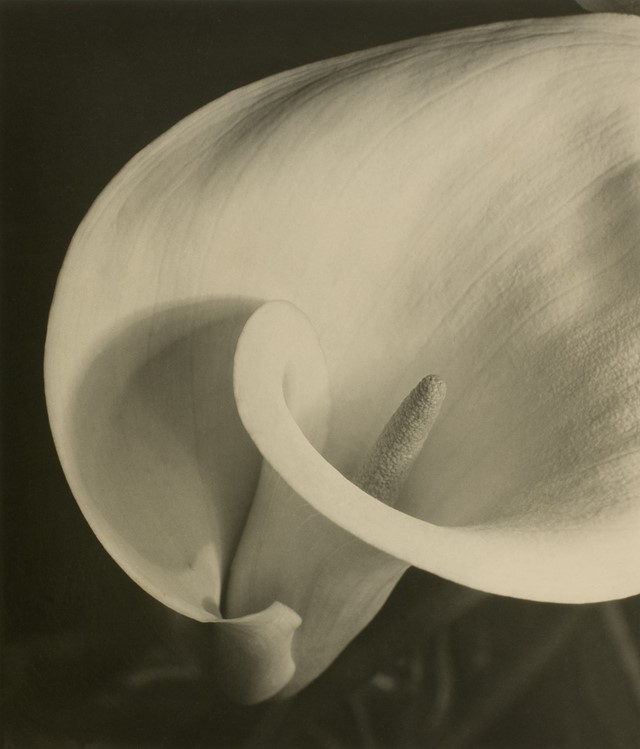

2. Imogen Cunningham, Calla, 1929

Georgia O’Keeffe famously rejected readings of her paintings as yonic allusions – but as McNear points out, perhaps the fault was not with her brush, but her subject matter. “That images of flowers function metaphorically as referents for sex is hard to ignore when a blossom is closely observed,” writes McNear, paying tribute to American Modernist photographer Imogen Cunningham. “Cunnigham’s use of the close-up to isolate and abstract the flowers form makes Calla an exemplary Modernist study. However, it also serves to focus our attention on how the spathe, the lily’s large, conical petal, embraces the phallus-shaped spadix, which carries both the male and female reproductive organs of the plant. Thus the picture, no matter how innovative or pure, can’t quite escape the overt sensuality of its subject.”

3. Sam Abell, Prize Winning Flowers, Alaska State Fair, 2013

Sam Abell spent 33 years capturing the world on behalf of the National Geographic, fostering a profound fascination with plants and flowers in the process. His shot Prize Winning Flowers, Alaska State Fair serves as a documentary image but feels oddly staged, too, with a laboratory-like precision.

4. Luigi Ghirri, Versailles, 1985

If ever you’ve gazed up at a spectacular historic stately home and considered both your own relative smallness and all the activity that that place has seen before you, you’ll find a kindred spirit in Luigi Ghirri. The Italian photographer was preoccupied with landscapes in which history had happened, so to speak; in his photographs, the book demonstrates, tiny human figures serve as measuring sticks by which to grasp the surrounding buildings’ scale.

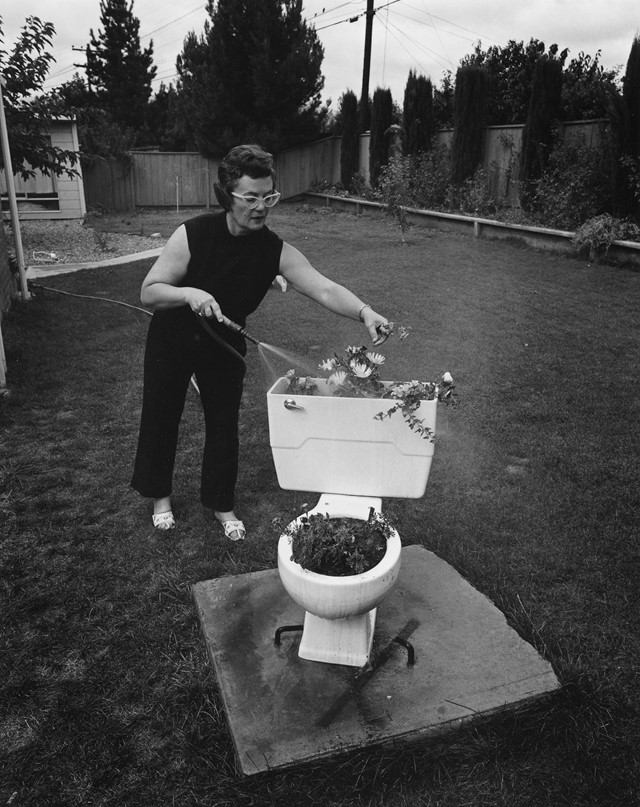

5. Bill Owens, Before the dissolution of our marriage my husband and I owned a bar. One day a toilet broke and we brought it home, 1971

Suburban gardens are sites of fun and fruition, so American photographer Bill Owens’ use of this one to map the dissolution of a marriage feels powerfully appropriate. In the late 1960s and 70s Owens worked on a groundbreaking photographic study of suburban life in post-war California, in which ordinary quotidian scenes are elevated, and infused with irony and empathy – both of which are present in this image.

6. Sharon Core, 1782, 2011

18th-century still life painting, or painstakingly recreated trompe l’oeil photograph? American photographer Sharon Core’s work sits elusively in the intersection between the two; she draws on established conventions around art historical tropes, reflecting playfully on the tension between photography and reality, and charting the evolving arrangements used in 18th-century painting all the while. “Perhaps most astonishing,” McNear writes, “Core grew many of the flowers used in the photographs.”

7. Mark Klett, Kem Brown in her Garden, Gimlet, Idaho, September 6, 1981

“Any gardener knows that when you’re out there, and you’re doing the work, the reason you love it is because it is the thing that takes you away from everything else,” she says. “That state of mind is kind of a fugue state of mind. When I look at this picture, she’s very focused, working on the edge of the wilderness, and she’s in that fugue state of gardening, of processing. This was obviously a long exposure; the moving hands are what communicate the action of the gardener.”

8. Jeanette Bernard, Two women with wheelbarrow, c. 1900

The George Eastman behind the eponymous museum – which houses one of America’s largest photography collections – was also the pioneer founder of Eastman Kodak, to which the pursuit of photography as an amateur hobby is largely attributed. It makes perfect sense then that amateur photographer Jeanette Bernard’s charming snapshot Two women with wheelbarrow be included in this book among some of the medium’s greatest icons. “Atypically,” McNear writes, “Bernard took photography seriously enough that for some 20 years she regularly entered amateur competitions sponsored by the popular illustrated newspapers, and in 1907 she won the Leslie’s Weekly competition ‘Who Is Our Best Amateur Photographer?’, which included a $20 prize.”

9. Eugène Atget, Lys (Lillies), 1916–19

Sitting in contrast to other more static floral arrangements, “[Eugene] Atget’s flowers exist in real space and time,” writes McNear, “the place and the moment he released the shutter”. There’s an innate mortality to this lovely image, paired with another similar in the book, however: “As a consequence the viewer is looking at active pictures that recorded the life of the lily while simultaneously anticipating its death.”

10. Larry Sultan, Los Angeles, Early Evening, 1986

“This picture is not necessarily from a body of work about gardens, but nonetheless we found it to be an incredibly compelling picture in a garden,” McNear explains over the phone. It was taken from the American photographer’s iconic Pictures From Home series, in which Sultan documents his parents in their California home to poignant effect. “He writes a lot about the landscape of the San Fernando valley and these spaces between suburban homes, and so while this is a single picture that we have repurposed, it is very true to Larry’s broader body of work.” There’s an ambiguity at play here, too, McNear continues; does Sultan’s father see him from the living room window?

The Photographer in the Garden is out now, published by Aperture.