It is part way through a purgatorial stint in California’s Silicon Valley, and photographer Niall O’Brien – whose girlfriend works for Apple, and has been relocated there – is bored. The couple are living in an apartment block in Campbell, a sprawling city that melds at its edges with the neighbouring Los Gatos and San Jose, the three cities connected with a single seven-mile stretch of road, Bascom Avenue. The nondescript, single-storey landscape is like that you might see in passing on the freeway, out of a car window. O’Brien, though, is stuck there – and he’s got nothing to do.

“I had so much time to spare and I just couldn’t get the place; I was warned and pre-warned that it was going to be fucking boring,” O’Brien later recounts over the phone from Los Angeles, where he has since moved. “It was what you would expect, just strip mall after strip mall and Panda Express – the fanciest thing near us was a Whole Foods. I’d end up going there loads to get a break from the banality. I drank juice.”

It made for that most pressing of issues for somebody who makes images for a living: there was nothing to photograph. It wasn’t that O’Brien wasn’t attuned to the vast, uneventful roadways of America – the Irish photographer’s best known series, Porn Hurts Everyone, was taken over the course of a 4,000-mile roadtrip across the country’s Northwest; more recently he installed himself in one of Louisiana’s swampland communities – but here, with no distractions, his eye was blocked.

That is, until a chance encounter set his latest series Three Cities, which goes on display at London’s Sid Motion Gallery this evening, in motion. A homeless man, Blake, had begun to live underneath the couple’s apartment block and, in a way typical for those with roots in Ireland, O’Brien struck up a conversation. They ended up going for breakfast; in the coming weeks, Blake would tell O’Brien his life story, a fantastical tale that spanned time and continents, and O’Brien would begin to film him.

Over the time the photographer spent in California, Blake would become the nexus on which the ideas behind the series would gather – he was, it transpired, the person who suggested the name Three Cities – though in the final collection, he only appears in a handful of photographs. “He was a catalyst, but it wasn’t a sociology thing,” O’Brien says. “The series became about this idea of area, but he just happened to be there and be this huge insight, this very honest point of view.”

It was partly down to the way Blake’s presence illuminated the discordance of the Santa Clara Valley; on the one hand there are gleaming compounds where the future of tech is mapped out, and on the other, the poverty that marks Campbell and its neighbouring cities is unavoidable. With this in mind, the banal landscapes revealed themselves as a willing subject, and O’Brien began to photograph again. “I just kept shooting and shooting and shooting and then when I returned to England I put it all together and I realised that there was this abundance of work,” he says.

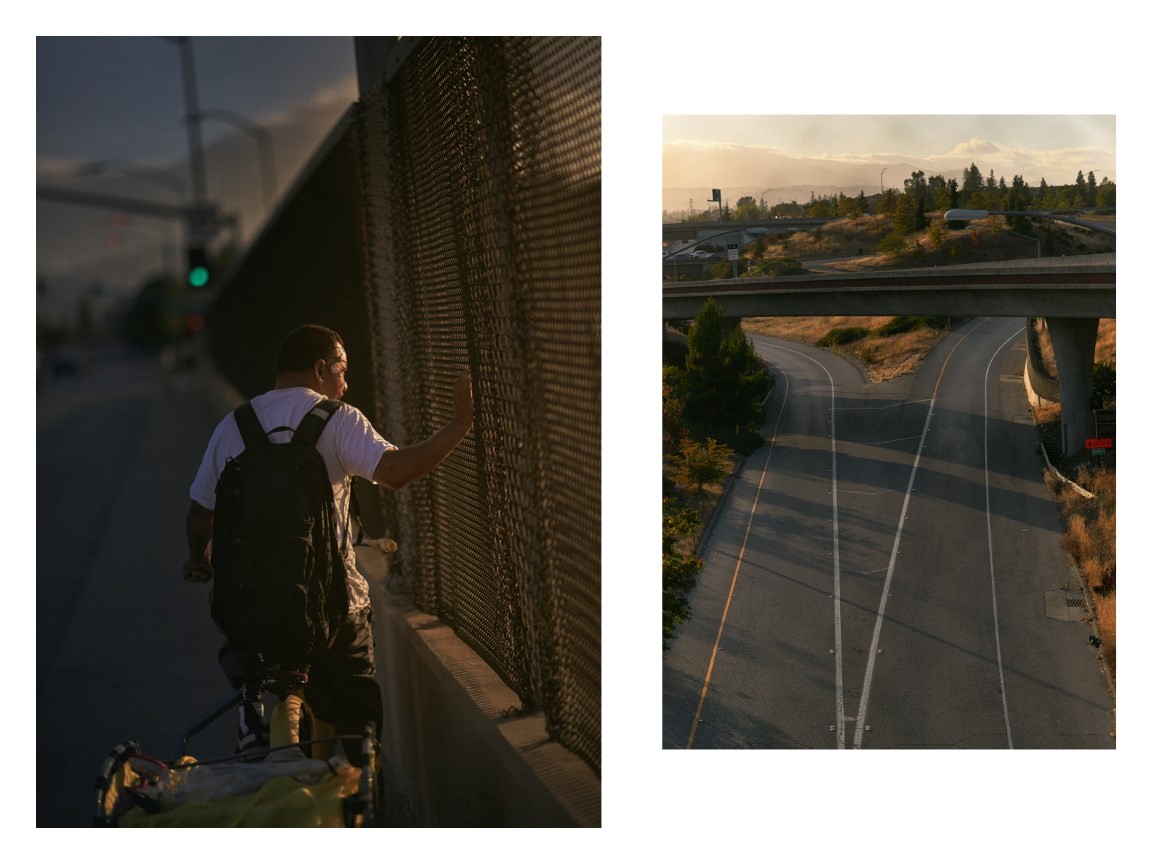

From then on each day he would choose to walk left or right, towards either Los Gatos or San Jose, until he reached the end of Bascom Avenue, just as the evening settled. “I decided to leave the house at a certain time in the evening originally, and just walk up and down,” he says. That timing was crucial – each photograph is lent the purple haze of dusk, or a flare of orange as the sun sets. In this light, the banality of the landscape is transformed; O’Brien worked in the tradition of William Eggleston, or Jeff Wall, before him. “I don’t think I would have seen the beauty in it if I didn’t have a little bit of help with the light… It’s so wonderful that it makes that uninteresting thing interesting.”

The selection of photographs which make up the exhibition, though small – there are thousands more he could have picked, he tells me – provide a portrait of a place. In one, a man sits waiting at a bus stop, unaware he is being photographed. In others, O’Brien’s lens is drawn closer to a wilting flower or a drooping American flag. If they are visual metaphors for a country in flux, it is the few of Blake, and his girlfriend, that are most arresting. A pair of images displayed next to each other show their hands passing dollar bills to one another, all nerve and sinew. In another, one of the few portraits, Blake’s girlfriend lies looking away into the ether, her eyes half shut. They feel temporal; as if their subjects are stood on the precipice.

“I was very aware of what I was experiencing with this huge contrast between what Silicon Valley stands for right now, and what the situation is from a different perspective,” O’Brien says. “In California they have a rule called the Safe Parking Program which is set up to allow people to sleep in the cars, because the rent there is so unaffordable that you have teachers and nurses sleeping in their cars. It’s really fucked up. There’s a huge contrast of wealth and poverty.”

Over the time he spent there – split between returning back to London, and also to Lourdes, where he is currently photographing the site of pilgrimage in similar terms – the walk became ritual, or compulsion. “Don’t get me wrong, towards the end you’re like ‘oh fucking hell, I don’t know if I can do this again,’” he says. “But then you’re walking for like two hours and then you take one photo which you know works and without sounding cheesy, it’s worth it.”

The result is a welcome proposal for working slowly – for allowing each photograph to prove its worth, to have a reason to exist. “I think it’s exceptionally important as a photographer to justify your work, because it’s so easy to do now,” O’Brien says. “My mum took a photo the other day, and I was like ‘woah’. It was a sunset, and it was amazing. Not to put my mum down, but if that can happen, you’ve got to elevate your own photography to a level where it’s worth a conversation.”

It is a way of thinking that has led him away from many of his contemporaries, who are increasingly pressed to prove their worth in the number of followers they have on Instagram. Not that he doesn’t use it – he has a healthy following of over 7,000, and he has recently discovered the joys of Stories – but you won’t find him documenting his life on there. “Can you imagine going on holiday and just taking pictures every ten minutes?” he says. “I mean, in my head that’s a pretty shit holiday. Although, the pictures say otherwise – who’s telling the truth here?”

In this attitude he has liberated himself from expectation. Three Cities sets a new precedent for allowing photographs to brew, to allow the subject – here, a single, seven-mile stretch of road, and those on it – to reveal itself on its own terms. “When I was younger I definitely had a huge amount of anxiety embedded in me for success and for achievement, but now I’m so happy just plodding along,” he says. “I don’t think I’ve felt more confident in my life about always doing work, simply because I’m not doing it for any other reason but just to make it.”

Three Cities: An exhibition of new photographs by Niall O’Brien runs at Sid Motion Gallery, London from April 27 until May 26, 2018.