A new exhibition at Fondazione Prada takes a philosophical look at solitude. Here, AnOther speaks with the show’s curator Dieter Roelstraete

It was a family trip to Jamaica that brought into focus the real world implications of philosopher Dieter Roelstraete’s life’s work. “The one thing I was looking forward to most was switching off my phone. I didn’t want screens or computers. I didn’t bring a laptop,” he explains, sitting under the extravagantly frescoed Baroque ceiling of Fondazione Prada’s Ca’ Corner location in Venice, where he’s just opened his latest exhibition, Machines à penser. “But when I arrived there was WiFi,” he continues. “Even in paradise, we were unable to escape the prison of connectivity.”

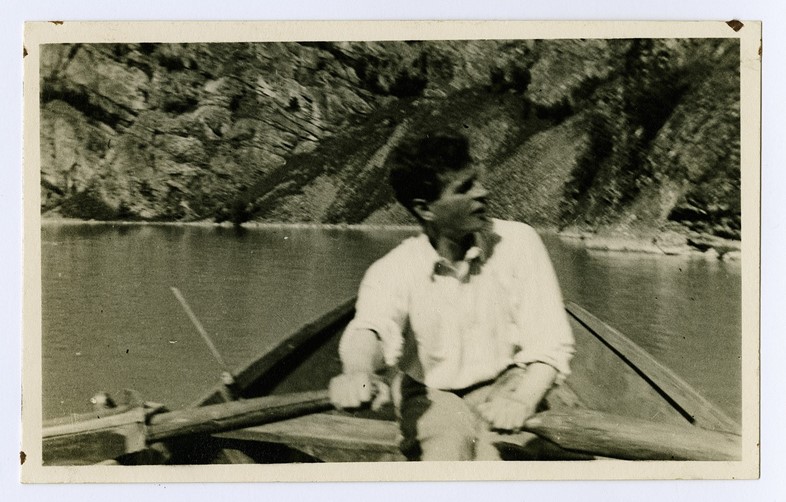

The desire to disconnect is a longtime academic curiosity of Roelstraete’s, who was trained as a philosopher at the University of Ghent and currently works as a curator. With this exhibition, his curatorial mission was to explore ideas of exile, escape and retreat in relation to creativity, choosing to do so through a somewhat unconventional entry point: the philosopher’s hut, something philosophers Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger and Theodor Adorno have been connected to in their respective careers. In the exhibition, Roelstraete explores the hut as both an essential bricks-and-mortar shelter for cultural production and a metaphor for the seclusion required to fulfill intellectual potential. A ‘room of one’s own’ for male continental philosophers, if you will.

“The triangulation of Heidegger, Wittgenstein and Adorno together with their huts is what really sparked the curatorial argument to make an exhibition,” explains Roelstraete. “I wanted to look at these structures as a way of talking about the relationship between thinking and place, between creativity and isolation, between reflection and solitude.” Visitors to the exhibition are invited to step inside mock-ups of both Wittgenstein’s and Heidegger’s huts, while Adorno’s life in Los Angeles as an exile during the war is recreated through detailed maps and photography by Patrick Lakey. Together, they provide a doorway into the three philosophers’ isolated physical realities during their most prolific stretches of time.

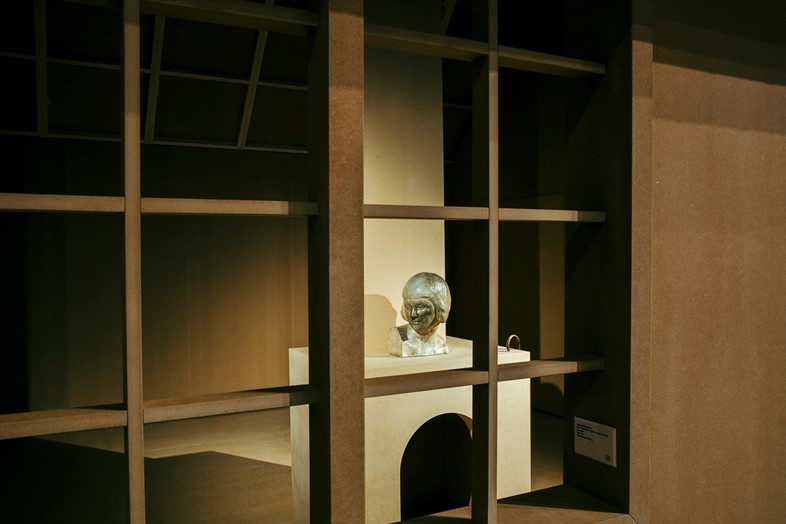

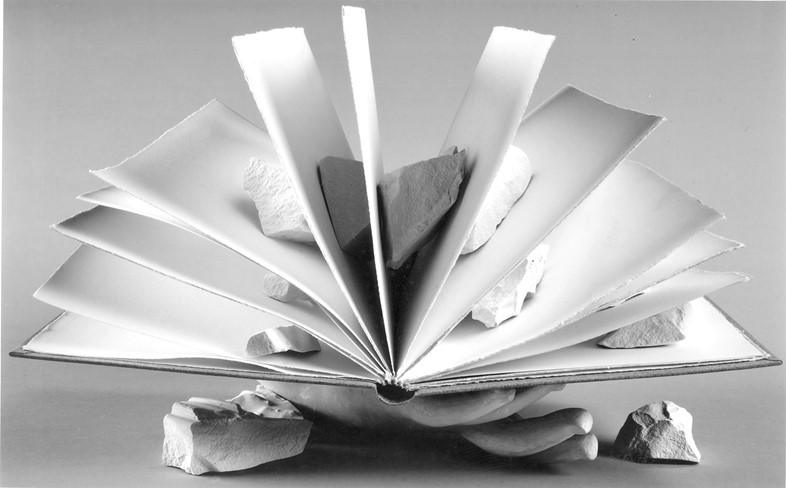

In addition to the huts, the exhibition considers a broad range of work by artists and intellectuals who have dealt with the idea of retreat and escape within their own practices. Gerhard Richter’s paintings of the remote Engadine landscape sit alongside a historical study of the hermit Saint Jerome, who spent his life alone in the Syrian desert translating the Bible into Latin. New work was commissioned for the exhibition, too: Goshka Macuga created a series of vases that take the form of the philosophers’ heads, as well as plans she made, unfortunately unrealised, to turn Fondazione Prada’s palazzo into a mossy, hut-topped fjord overlooking the grand canal. The Scottish poet Alec Finlay responded to brief with an epic poem tacked to cherry red lattice work enveloping a richly decorated Renaissance era studiolo, and Portuguese designer Leonor Atunes created a series of chandeliers inspired by the house Wittgenstein built for his sister in Vienna. We spoke to Roelstraete about his inspiration behind the show, his thoughts on exile, and why escapism should be seen as a virtue.

On the premise of the show…

“The title of the show is Machines à penser, an allusion to the famous quip by Le Corbusier, who called a house a ‘Machine à Habiter’ – a machine for living. It looks at philosophers who have been associated with huts in various degrees. The two most important ones are Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger who both had historical huts built for them. Heidegger’s hut still exists today in the Black Forest village of Todtnauberg, while Wittgenstein’s hut used to stand on the edge of a fjord in the Norwegian village of Skjolden. Thirdly, there’s the figure of Theodor Adorno, who never lived in a hut or built himself a hut, but strangely enough had this sculpture named after him by Ian Hamilton Findlay, who is British sculptor and poet who made this installation in 1987 named Adorno’s Hut. My discovery of the existence of the Adorno’s hut many years ago is what triggered the thought process that eventually culminated in the exhibition.”

On the virtue of escapism…

“One thing that I was interested in doing was to stage escapism as a virtue, not a vice. If you’re called an escapist, it’s derogatory, right? Escapism is something that’s bad, right? Entertainment is escapist. It’s meant as a slur. I was interested in painting a picture of escapism as a completely legitimate attitude and productive for a variety of things: thinking, art making, but also perhaps social interaction.”

On exile…

“If part of the exhibition is the relationship between thinking and space in the relative comfort of the space of one’s own choosing, we also show the connection between thinking and space if you are forced into that space. If all you have left of your home is your language. On display is a map that shows where Adorno and Horkheimer, who were immigrants from Germany, used to frequent when living in LA in the 1930s and 1940s during the war. It’s where the cream of the crop of German Weimar intellectual culture in LA used to live in that period. Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, all of these people. Hanns Eisler, [whose music is played in the gallery] is somebody who fled to the US, was initially welcomed with opened arms, and then in 1949 when the Cold War was gathering pace, was forced to leave again because of his Communist sympathies and return to his native Germany. He’s somebody who has hounded his whole life, on the run his whole life, and still managed to create.”

On the universal desire to retreat…

“You can make the same show about islands, or you could make the same show about the desert. In both cases, they’re spaces that are the recipients of our desire to escape. To flee and break free from connectivity, from the attention economy, from all these things. And so, that’s I think why this exhibition is relevant. This is something that we all dream of, that we all want. If you live in a big city, you probably dream about the mountains.”

Machines à penser is open at Fondazione Prada, Venice until November 25, 2018.