An exhibition on the Venice Lido celebrates the floating city’s time-honoured festival through the years

It seems fitting that the first city in the world to host a film festival was one built on reflections. Venice is a place constantly remade and distorted in lapping waves, a network of streets where every sunrise appears cinematic, with a globe that bobs over a watery horizon. Illusions and tricks of light are a daily occurrence in the city; flickering rolls of projected film reel seem right at home. It feels inevitable that it was here, on the razor thin island of the Venice Lido, that the terrace of the grand Hotel L’Excelsior became crowded with wicker chairs as audience members flocked to the world’s first film festival 86 years ago.

2018 marks 75 competitive editions of the world’s oldest film festival since Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde opened on the evening of August 6, 1932. To celebrate the milestone, the director of the Cinema Department of the Biennale, Alberto Barbara, has curated an exhibition using the festival archives to present an array of photos, films, posters and documents from the crowded screens of festivals past. Stretched out across the frescoed ground floor rooms of the iconic but abandoned Hotel des Bains the exhibition is an expansive and immersive experience. Columns with peeling paint are flanked by large statues of Venice’s signature lions, with a red-carpeted entrance hall giving way to walls awash with an array of familiar faces. It is here that Barbara helps remind us of the wealth of film history this small strip of land and its festival holds, on the universal stage.

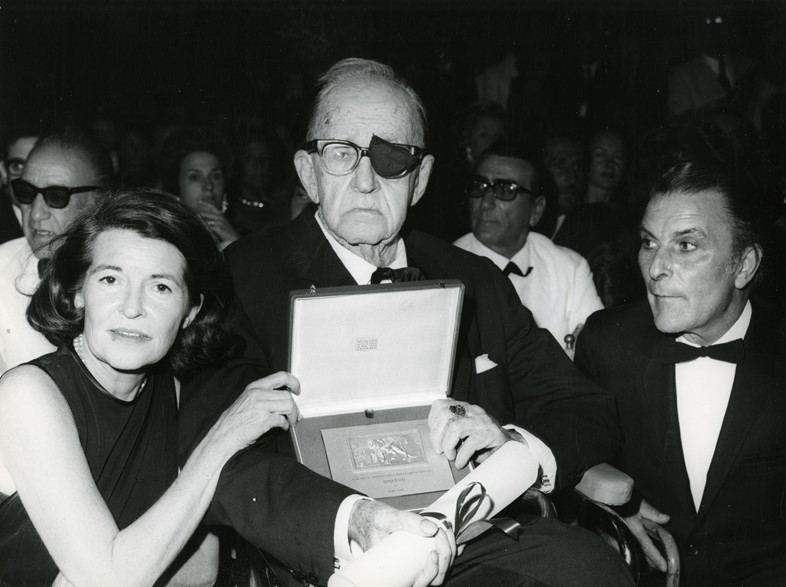

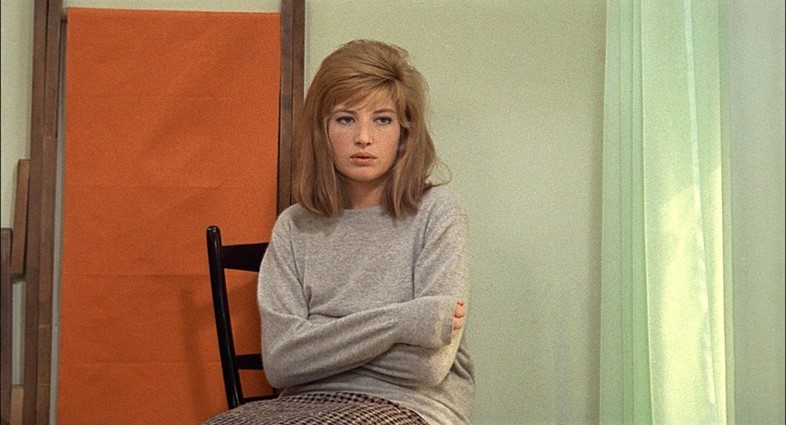

Before the Cannes film festival came along in 1946, Venice ruled the cinema world. Stills of screen sirens from the archives eloquently illustrate how. One moment Greta Garbo is swept up in the arms of John Barrymore in Grand Hotel, the next she’s lounging on a carpeted floor being fed grapes by John Gilbert in Queen Christina. Ingrid Bergman glowers in a frame from Rossellini’s Stromboli. Marlon Brando smoulders for A Streetcar Named Desire, Audrey Hepburn shivers as she slips her hand into the stone mouth of truth in Roman Holiday, Claudina Cardinale reclines on a diving board. We see how Antonioni wins the Leon D’Oro for Il Deserto Rosso with Monica Vitti in silk by his side in 1964. Pasolini smirks on set in signature shades, Jean Renoir yawns in a water taxi, Vittorio de Sica rides with friends by the Rialto in 1971. Lauren Bacall relaxes on the terrace of the Hotel L’Excelsior, while a young Isabella Rossellini jokes with Alberto Moravia.

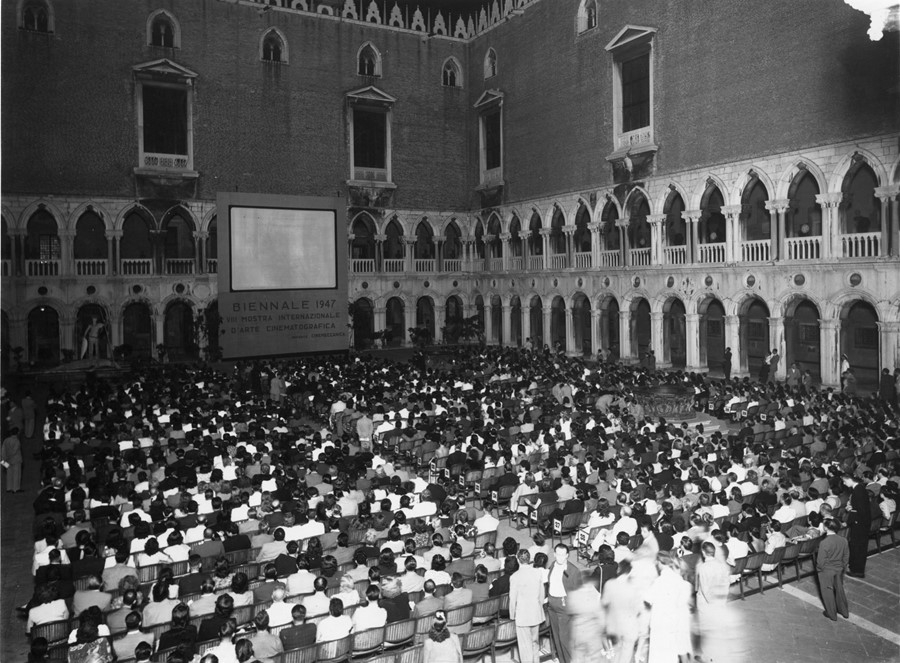

The festival has transformed over the years. Starting on a hotel terrace, then moving to the courtyard of the Doge’s Palace, and now located in specially built cinema complexes, its many incarnations are all examined. It’s a credit to Barbara’s curating that the difficult years of what he calls “embarrassing political difference” during the war are addressed rather than ignored and stand alongside the golden years of the Biennale’s inception. The resilient honesty of recognising the festival’s part in putting on military screenings during the occupation, in which swastikas hung from gilded balconies and festival organisers joked with Goebbels, only adds more fuel to its vibrant rebirth.

It’s immensely illuminating to see films placed together as they were originally seen. In 1972 Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange was screened alongside Bob Fosse’s Cabaret with Lisa Minnelli. In the 1983 competition Star Wars: Return of the Jedi was seen by audiences who had also enjoyed the legwarmer-clad steel worker Jennifer Beales in Flashdance. Three years later, in 1986, Aliens shared space with Merchant Ivory’s A Room with a View, and Eric Rohmer presented his Le Rayon Vert side by side with Nora Ephron’s Heartburn. 1993 saw Jurassic Park come head to head with Juliette Binoche’s Three Colours Blue, while in 2003 Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation accompanied Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers. Each juxtaposition gives us pause as we recapture the time that engendered it.

Venice has always known how to surprise its audience. Alongside films that we now deem classics, such as Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet, or Orson Welles’ Macbeth, the floating city has been a base for innovation and the avant garde. In only its second year the festival saw Gustav Machaty’s Ecstasy screened with Hedy Lamarr appearing in the first nude scene in the history of cinema. Venice, in Barbara’s words, has an “inexhaustible urge to renovate and experiment” and this year is no exception, with an entire section of the Biennale dedicated to virtual reality.

The Venice film festival will always have a special place in the world of cinema. “It allows us to discover films that can help us to interpret the past behind us and decipher the future ahead of us,” Barbara observes, “unshackled from the dictatorship of ‘presentism’”. It is here among rippled reflections that new creative visions are made visible to the world; it’s a story that’s still being told before watchful eyes.

Il Cinema in Mostra runs at Hotel des Bains, Venice Lido, until September 16, 2018.