Travelling to the country on a commission from The New Yorker, Max Pincker’s photographs capture the regime in an artificial light

When Belgian photographer Max Pinckers received a commission from The New Yorker to photograph in North Korea he knew it would be impossible to shoot what, how and where he wanted. He and journalist Evan Osnos would be accompanied 24/7, their every move scrutinised. “In North Korea, nothing is left to chance,” Osnos writes in an insightful accompanying text. “Every contact with visitors, no matter how incidental, is controlled and channelled to achieve an effect.”

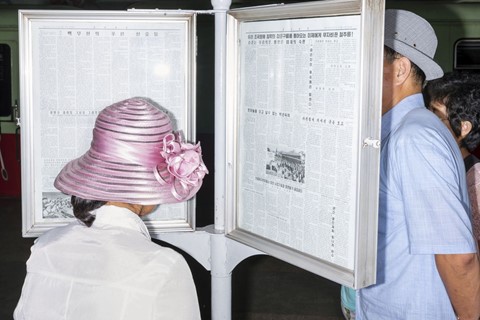

With the knowledge that any attempt to show the reality behind the regime’s façade would be futile, Pinckers and his wife, Victoria, who assisted him, decided to shoot with flash to create an artificial aesthetic reminiscent of advertising or propaganda posters – an approach that deliberately drew attention to the constructed nature of what they were encountering. By flooding his pictures with light and picking out seemingly inconsequential details, Pinckers quite literally shines a spotlight on North Korea’s propaganda-fuelled regime.

When Pinckers returned home, he realised the potential of the work and turned it into a book, Red Ink. AnOther spoke to Pinckers about the project, which was recently awarded the Leica Oskar Barnack Award 2018.

On what it was like photographing in North Korea…

“In a way we knew what to expect – we knew that government officials would escort us and it would be difficult to interact with people and move around freely – so we were well prepared. The gentlemen who were with us were very friendly, open and easygoing, which gave me the feeling of being very free, somehow. It was only afterwards I realised that that was a very smart [approach]; if you make your guests think they are free, you have even more control. I thought that was a powerful and effective way of manipulating the mind. You feel comfortable so you’re receptive to the stories you’re told and places you’re shown.”

On lighting his images in a bold, hyperreal way…

“The approach of using a ring flash-type set-up was motivated by practical considerations – I knew I’d have to work quickly and wouldn’t be able to set up scenes or interact with people. I’d developed the technique beforehand and it worked well, especially when you apply it to the setting in North Korea, which already has a strange colour palette and weird [ambiance]. I could play around with form, colour and a purely aesthetic approach. Anything could be photographed and it would make sense in this context.”

On how this project sits within his work as a whole…

“I’m always looking to stage things on location and thinking about manipulation in a documentary context and the boundaries of documentary photography, [asking] when is it objective and how can you reveal its construction. This was the only time I didn’t have to manipulate anything because the preconceptions of North Korea are so present and powerful everyone thinks that everything is manipulated anyway. That made it very interesting for me – I didn’t have to stage anything, I just had to photograph.”

On the importance of questioning how we document what’s around us…

“It’s always been my motivation and drive to try and deconstruct the question [of what documentary photography is], to see how images can be used and how we try to understand them on different levels. The more I dig into that, the more interesting it becomes to me and the more different approaches or strategies I come across and can work with. Research is a crucial part of the practice that is documentary making and it’s important to be informed and to think critically about what you’re doing – not just in terms of the subject matter, but also the different approaches you can take.”

Red Ink, published by Max Pinckers, is out now.