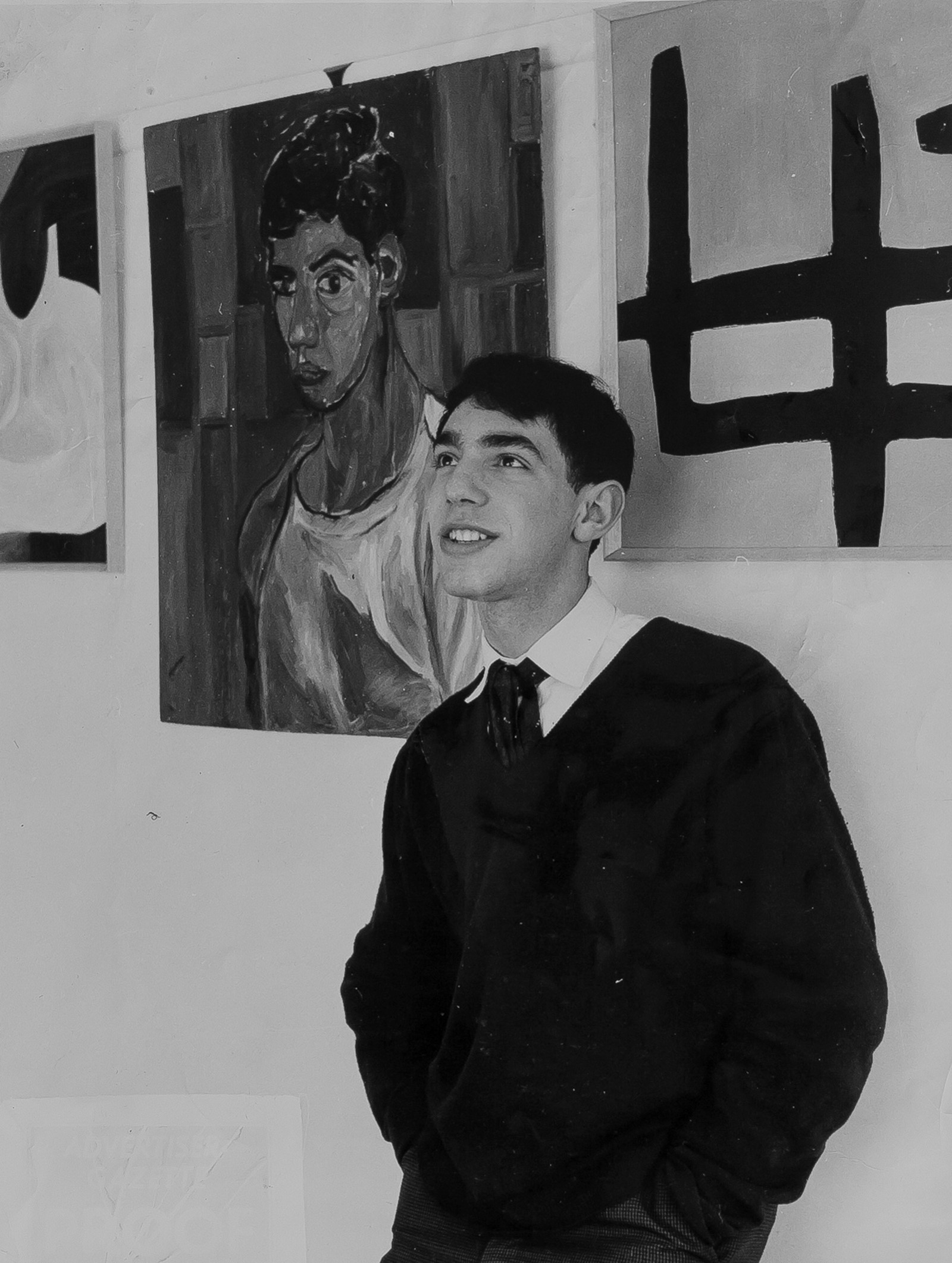

In the first room of PROTEST! – the Derek Jarman retrospective that opened last week at Dublin’s Irish Museum of Modern Art – the only picture hanging is a mournful self-portrait from 1960, painted when Jarman was just 18. At the time, he was leaving school to embark on a BA course in History and English at King’s College London, and he sits with a dejected downward gaze. (It’s not difficult to figure out why Jarman might have been glum: in the same year, his plans to study fine art had been scuppered, after his father told him he had to complete an academic degree first.) Set against a backdrop of blue squares, it’s a charmingly adolescent take on frustrated creativity.

But this isn’t the only source of blue: seeping out of the curtains in the adjoining room is the intense, unmistakable hue of International Klein Blue. The ghostly voices of his longtime collaborators Tilda Swinton and Nigel Terry recite lyrical stanzas, telling the story of his day-to-day life as a gay man living with HIV in abstract, dream-like terms. Acting as a kind of soundtrack to the portrait, it makes for a neat introduction to Jarman’s vast body of work. The two pieces bookend a life spent immersed in art, film and literature, charting the evolution of his concerns from the micro to the macro; from the emotional turmoil of growing up queer in 1950s Britain, to the sweeping injustices inflicted on the LGBT+ community many decades later by Thatcherism and the Aids crisis.

The landmark Dublin exhibition coincides with the 25th anniversary of Jarman’s death, and brings together an unprecedented body of work from across the various chapters that made up his sprawling career. While Jarman is best known for the theatrical visuals and subversive political spirit of films like Jubilee (1977), Caravaggio (1986), and The Last of England (1988), his beginnings as a painter and visual artist are shown in their full breadth here for the very first time. As music journalist Jon Savage puts it in his introduction to Derek Jarman’s sketchbooks, published in 2013: “There are so many Jarmans that it feels strange to focus on just one aspect of the man.”

But while the exhibition covers all of these Jarmans, it also reveals new Jarmans that have never reached the public eye. One section includes books from Jarman’s library, curated by Professor Robert Mills, a Medievalist and art historian whose encyclopedic knowledge of queer history lends the exhibition impressive context. (Appropriate, however, for an artist who was just as likely to reference Elizabeth I’s court alchemist, John Dee, as he was to win the top prize at the 1975 Alternative Miss World as his drag persona Miss Crêpe Suzette.) Another sheds light on his collaborations with production designers and costumiers, including sketches for the breathtaking sets he produced for Ken Russell’s The Devils in 1971, five years before he would direct his first film, and the opulent historical costumes designed by Sandy Powell for films like Edward II (1991) and Wittgenstein (1993).

These collaborative efforts spotlight Jarman’s unlikely role as a mentor and nurturer of talent, that inspired fierce loyalty in those to whom he gave their first break. Powell’s first foray into the world of film was with Jarman; today, she regularly collaborates with Martin Scorsese and has received three Academy Awards for Best Costume Design. Her most recent nomination in 2018 was for the sumptuous costumes of Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Favourite – which, with its offbeat and blackly comic take on the tropes of period drama, surely takes cues from Jarman’s own experiments in the genre. So too is there his greatest muse, Tilda Swinton, who received her very first role in Jarman’s Caravaggio as one of the Italian artist’s dangerous liaisons, and who is set to reprise her role in Blue for a live performance of the film when the exhibition travels to Manchester next year. Joanna Hogg, meanwhile, met Jarman by chance in Patisserie Valerie in Soho in the late 1970s; they formed an instant friendship, and he encouraged her to pursue her interest in film by lending her a Super 8 camera.

But even if we’re seeing a comprehensive overview of his surprisingly prolific art practice for the first time, what makes it doubly fascinating is just how interlinked they are with his films. The ten-year gestation period of Caravaggio – which apparently involved 17 script rewrites – is represented in never-before-seen works he made while travelling around Italy for research. Two paintings, titled Pleasures of Italy, are a woozy mass of limbs drawn against a background of washed-out, gauzy white. As with the onion-like layers of history that exist within every Italian city, each peeling back reveals something unexpected: drips of paint and fragments of text aping Roman graffiti, and a dumping ground of broken ancient statuary. Oh, and a healthy dose of the erotic, too – it’s not hard to see them as representing debauched, Caligulan orgies.

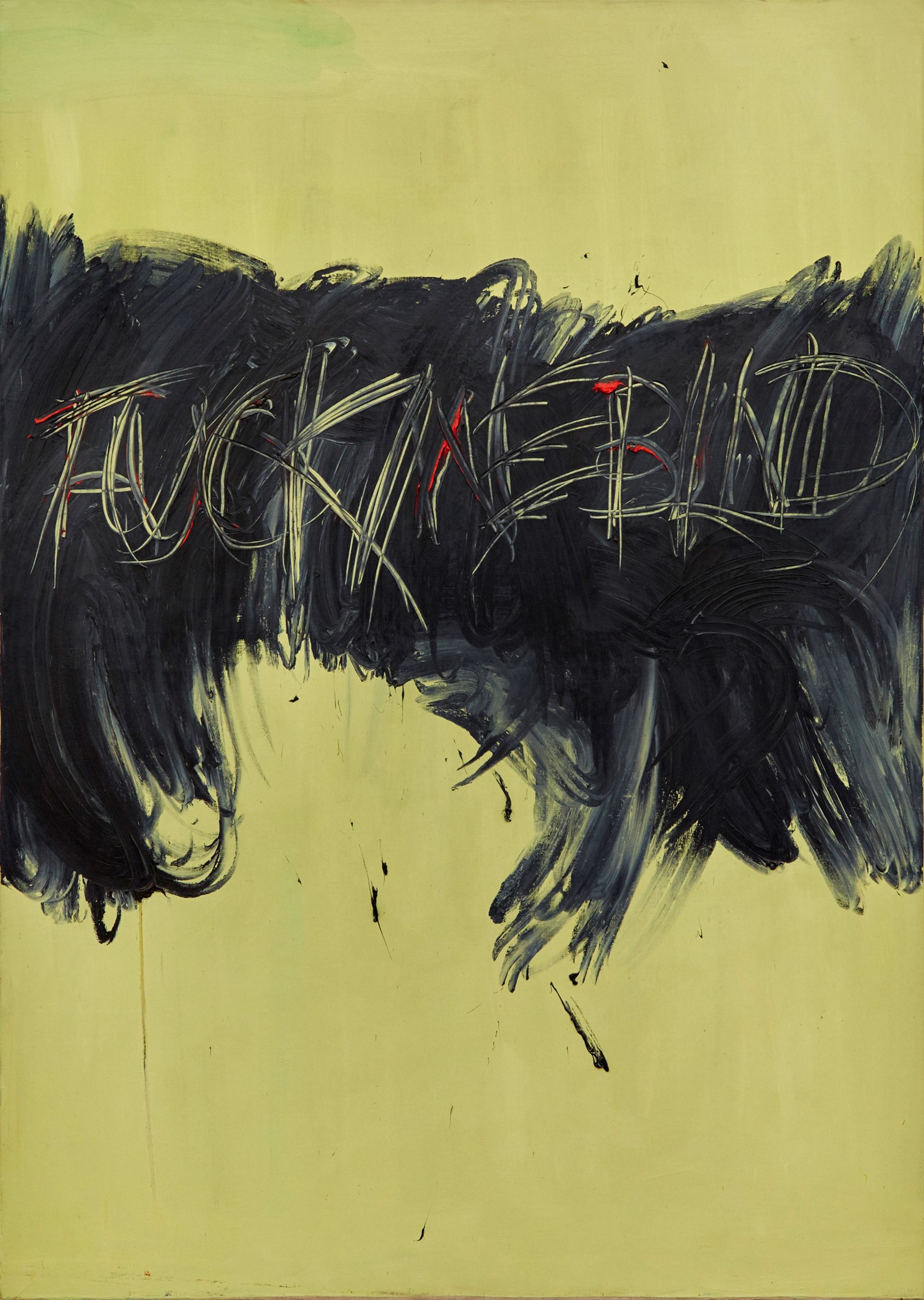

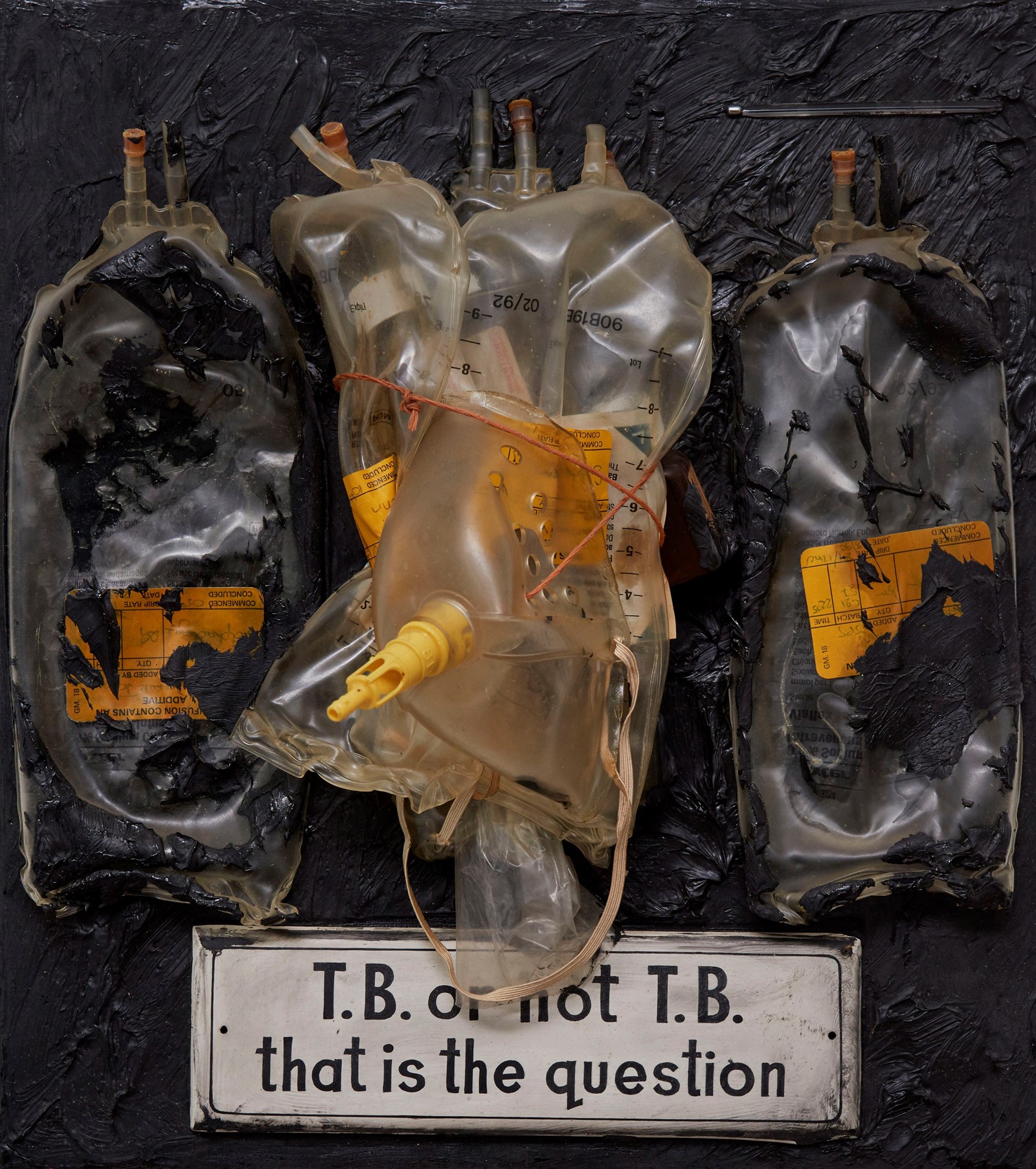

As his career progresses, this interest in sex – which was once more coded, visible only in the coy homoerotic pose of Dexter Fletcher recreating a Caravaggio painting for the film’s famous poster, or the ejaculating phalluses of his eerie, Goya-inspired “black paintings” – becomes bracingly political. Diagnosed as HIV positive in 1986, Jarman became one of the first public figures in Britain to talk openly about living with the disease. Video footage of a provocative exhibition he staged in Glasgow shows him taking journalists around a space plastered with homophobic, fearmongering headlines from tabloid newspapers, as two young men sleep in the middle of the room on a bed wrapped in barbed wire. We see Jarman’s “slogan paintings”: on enormous canvases, he scratches into thick impasto surfaces with slogans like “fuck me blind”, “evil queen”, and “Aids is fun”, many of them completed by studio assistants as he entered a phase of physical decline. Here, the Aids crisis and Jarman’s own struggles are spelt out with violent, anarchic glee – as with Tilda Swinton screaming and tearing apart her bridal gown in the climactic final scenes of The Last of England, this profound loss is recast as a kind of private apocalypse.

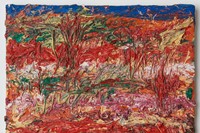

But despite this sense of finality, it doesn’t feel like Jarman’s concluding artistic statement. That would be, instead, the garden he had begun cultivating at his seaside home of Prospect Cottage in Dungeness (as the only area of Britain technically considered a desert, the landscape does have an appropriately end of days feel, however). Here, he seems to have found an unlikely peace in his final days, cultivating hardy succulents and cacti on the edge of England, and creating weird and wonderful paintings collaged from found objects he picked up on his walks along the Kent coast; driftwood and smashed glass, spent bullets and used condoms.

Here, the screening room showing Blue takes on a new, more dignified, significance. Even if the visceral despair of his slogan paintings still clangs in your ears after you leave the show, Jarman’s legacy isn’t one of nihilism – right to the end, as he drew on his rich cast of collaborators to put together Blue’s distinctive sonic panorama, it was one of defiance, celebrating what it meant to be creative in the purest sense of the word. As someone who could just as easily turn his hand to directing a music video for The Pet Shop Boys as he could sit down and write a book about his garden, Jarman’s body of work is a microcosm of four decades of British queer and countercultural history, seen through the gimlet eye of one its keenest documenters. And in Dublin, 25 years after his death, it can finally be seen in all of its magnitude – for the very first time.

PROTEST! is at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, from November 15, 2019 – February 23, 2020.