As Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music opens at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, chief curator Mary-Dailey Desmarais unpacks the late artist’s fascinating relationship with music

It must be a challenge to curate an exhibition about Basquiat these days. It feels like he’s reached saturation point: his work is splashed across Converse shoes and Tiffany campaigns, printed on Urban Outfitters T-shirts and Urban Decay eyeshadow palettes, or else etched, indelibly, into the skin of his many fans via those crown motif tattoos. In March, our sister site Dazed Digital even ran an article addressing this, asking if this level of fame and ubiquity was what he would have really wanted. This isn’t, of course, to say that Basquiat’s popularity and resonance within contemporary culture isn’t warranted: his art is inarguably good, its themes are topical and the artist’s cultural crossovers (dating Madonna, modelling for Comme des Garçons etc) add even more to his lore. But going back to my original point: it must be a challenge to curate an exhibition about this very-exposed artist.

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts’ new exhibition Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music, however, offers an interesting and novel insight into the artist’s life and work, shining a light specifically on his relationship to music: the artists he listened to; the scenes he was involved in; the musicians he befriended and worked with; and the deep and wide-ranging interests he had in the field. Basquiat’s father would play jazz and classical music in the house – according to his sister, who was present for the opening – and he would sit on the floor drawing as he did so. Years later, the artist would continue to play music while he worked – and yet music wasn’t just a soundtrack to his work, it was the lifeblood running through it. It bubbles up in his paintings, surfacing via musical symbols, and signposts to the musicians he admires, through the poetic application of words. It’s there on the canvases just as much as the paint.

As the exhibition in Montreal opens, its chief curator Mary-Dailey Desmarais speaks to four genres Basquiat shared a particular intimacy with, and which are explored so brilliantly through this show.

No Wave

“Basquiat was a big fan of certain no-wave bands like DNA and The Lounge Lizards. He became very good friends with Arto Lindsay [a member of DNA] and John Lurie [a member of The Lounge Lizards] and made flyers for them, many of the originals of which we have in our exhibition. He also made paintings or murals, in some cases, in places where these bands played – so Club 57 and Tier 3. We have this painting that went on the wall in Tier 3, that's not been seen before but it's very well documented because he made a poster and postcards after it, so we know where it comes from at least. He made a painting of James White and The Blacks, he also did this portrait of The Kipper Kids, which was this post-punk performance duo [made up] of Brian Routh and Martin Von Haselberg.

“He really was an active part of that scene of no wave and new wave and all of the kind of experimentation and spirit of DIY that was happening at the time. He was a regular participant in Glenn O’Brien's TV show TV Party, which was a public access television show, which often had kind of Club 57 regulars. Basquiat sometimes read poetry on it; other times he was in the control room. So he was really an active part of that. And then of course, as a member of the band Gray, he shared the stage with DNA and The Lounge Lizards – they performed at the same clubs and sometimes on the same evening, and you can see how that music is drawing from the culture of no wave and new wave.”

Hip-Hop

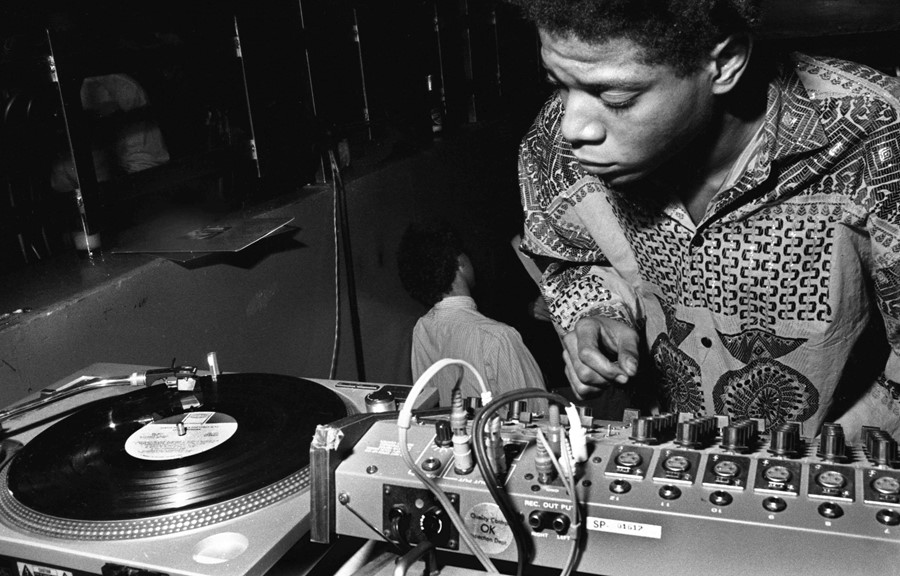

“Basquiat also became friends with some major people on the hip-hop scene. He was friends with Fab Five Freddy and the two of them shared a real bond over music. He was also friends with graffiti artists A-One, Toxic and A-Row, and he went on to produce this hip-hop single in 1983 with Rambo Z, who’s really at the heart of early hip-hop. Then when Rambo Z and Toxic came to Los Angeles in 1983 and performed at The Rhythm Lounge, Basquiat made these drawings of cars that are superimposed on the performance.

“He attended a lot of hip-hop concerts, but much more than that, he visually represented hip-hop culture through his art and participating in it as a producer and as a collaborator on some music videos. And he’s stepped in for Debbie Harry's video Rapture in 1981; he collaborated on paintings with Futura, Fab Five Freddy, Kenny Scharf and on other sorts of big graffiti paintings in the exhibition.

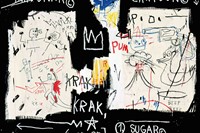

“Then also, of course, in many of his paintings. You can make a comparison between the compositional techniques he’s using and sampling and hip hop; how DJs were taking pre-existing sounds and creating new sounds. That’s something that Basquiat did; he sampled his own work, he took these photocopies and then he recombined them and created these radical juxtapositions that made new meanings like in hip-hop. In the portrait of Toxic, he’s connecting that through photocopies of his own work to jazz. He photocopies this one drawing in particular, that cites not only jazz but the slave-owning American president Andrew Jackson and these cartoons made by Max Fletcher in the early 20th century that were very kind of prejudicial, [with] no representation of Black people. Also Charles Correll and Freeman Gosden, who were two white actors who were hired to voiceover Black characters and give them these totally caricatural representation. So, he’s kind of staging this dialectic between authentic Black performance and cultural production and its frankly racist representations of Black people in popular culture. These paintings are really rich and complicated, and he was deeply invested in all the kinds of histories that are bound to music.”

Jazz

“Jazz was definitely the most important musical genre for Basquiat. His father played a lot of jazz while he was growing up. Very early on, his father described in an interview how Jean-Michel drew on the floor while he played his jazz. Art and music came together very early in [Basquiat’s] world. Through listening to that music, he also developed a profound appreciation for pioneers of bebop, which is a more avant-garde kind of jazz that was really spearheaded by Charlie Parker. He cites Parker repeatedly in his work, he cites Parker’s tragic loss of his daughter at the age of two, and he understood Parker among many other jazz musicians as real champions of Black excellence, and he wanted to celebrate that and his work.

“Basquiat is somebody who was profoundly aware of the lack of representations of Black heroes in art museums. He once said, ‘I don't see enough Black people on the walls here’. He set out to celebrate Black creative expression and examples of Black excellence that he found in these jazz musicians. Certainly, in the case of Parker, he admired his improvisation and the depth of his art. I don’t want to speculate but Parker died too young himself, and it seems that Basquiat saw in him a kind of kindred spirit. When you look at the painting Charles the First, on the bottom it says ‘young kings get their heads cut off for living’. It’s like he understood the pitfalls of celebrity and also identified with these artists, as a Black artist who confronted racism.

“He and Fab Five Freddy spoke about not being able to get a cab in New York City. And George Condo recounted to me the story of where he and Basquiat went to some party in Los Angeles and the bouncer said to Condo you can come in, but the bouncer said [to Basquiat], ‘We don’t accept your kind in here’. Obviously, that was deeply painful for Basquiat. Condo did not go into the party and said, ‘Well, we both left, and we just went back to the house and listened to jazz.’ That to me, was very interesting. Getting refused at the door and then going back and just listening to jazz – it shows that it was more than just a soundtrack that he listened to, it meant more to him and was actually a structuring element to the work that he made.”

Music of the Black Atlantic

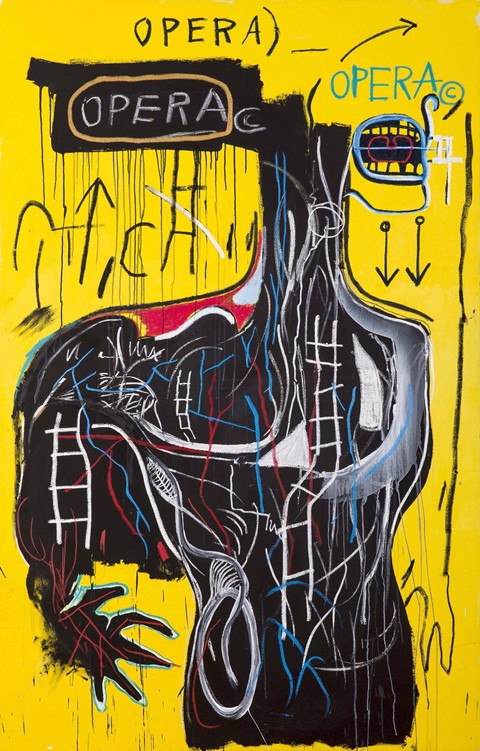

“Basquiat was really interested in the African roots of certain African-American musical genres like Zydeco, Mississippi Delta Blues, and even jazz, born in New Orleans. He was looking at the African roots of those genres and the transmigration of certain cultural practices from Africa, through the Middle Passage and through the slave trade. This is a subject that you can see in his work – for example, the painting from the Pompidou Slave Auction. Here is a painting in which he’s depicting human beings being forcefully transplanted via boat to North America. On the bottom right, he writes the initials PRKR – which is the way that he wrote Charlie Parker – so in the space of this single painting, he’s connecting the history of jazz to the history of slavery. In another painting like Negro Period, he cites Bob King and the moon landing, but also African animals. He’s creating these radical juxtapositions that show that he was really interested in the way that certain African cultural practices were brought to the United States and persisted through music.

“He's somebody who read and really admired Robert Farris Thompson’s book, Flash of the Spirit. Robert had a crazy intellect, he spoke ten different dialects of African languages and Basquiat referred to him as his favourite living art historian. He actually commissioned Robert Farris Thompson to write the essay for his second solo show at Mary Boone. But why is that important? Because you can see that book talks about the culture of the Black Atlantic, meaning the culture that developed around the transmutation of African cultural practices once they hit America and the Caribbean.

“You can see Basquiat citing that book when he makes certain symbols like that figure in the Untitled 1987 painting. It’s a form of proto-writing, found in West Africa. That symbol, as explained in Thompson’s book, means ‘all this world belongs to me’. He’s copying symbols from that book in there and so he's clearly very interested in the culture and specifically the musical culture of the Black Atlantic.”

Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music is on at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts until 19 February 2023. The exhibition is organised by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the Musée de la musique – Philharmonie de Paris.