On the 20th November 2012, what is purported to be the last typewriter made in Britain rolled off the conveyor at Brother UK’s factory in Wrexham...

On November 20, 2012, what is purported to be the last typewriter made in Britain rolled off the conveyor at Brother UK’s factory in Wrexham. The demise of the device can be seen to mark the last chapter in manual word-processors, passing the torch from the visceral clack of electronic keys to the near silent clicks of a laptop keyboard. Yet, it can be seen that the typewriter remains a recurring cultural motif, in literature, cinema and music, a status that means its continued existence should never be in doubt.

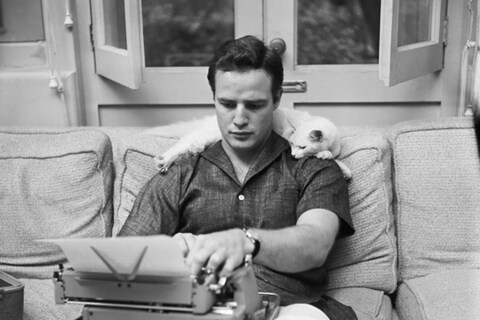

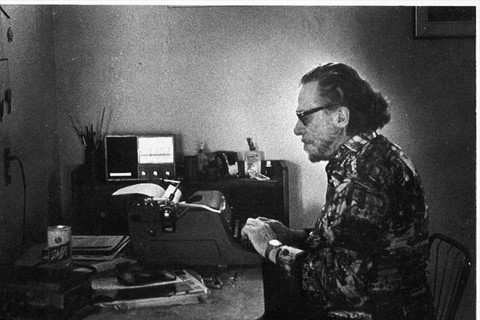

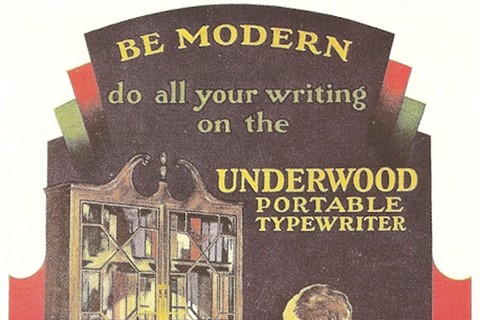

The humble typewriter is so much more than a writing device. It is visual shorthand for the writer with ink on his fingers, of a certain literary intellectuality, of passion and purity of thought. It is of the past – never more so than now – yet is at once a very current obsession; a part, alongside vinyl records and Cary Grant glasses, of an increasingly dominant culture of nostalgia. Despite being a commonplace item in offices and houses for much of the twentieth century, since the dawn of the computer age, the humble typewriter has garnered a rose-tinted aura, redolent not of the mechanic output of 1950s typing pools, but rather indelibly associated with the romantic figure of the aspiring author.

"Since the dawn of the computer age, the humble typewriter has garnered a rose-tinted aura of nostalgia, indelibly associated with the romantic figure of the aspiring author"

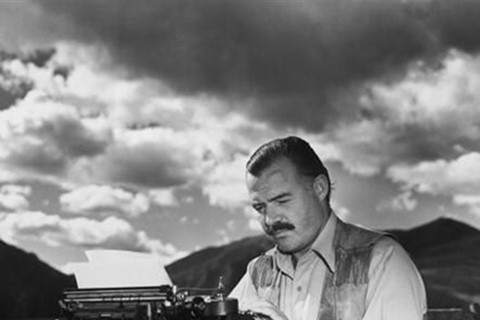

And this association makes sense. Since Mark Twain submitted the first ever typewritten novel in 1883, the clack of the typewriter has held us enthralled. We have the image of Jack Kerouac typing furiously at more than 100 words a minute on the 120 foot long scroll that became On The Road; Ernest Hemingway composing while standing up in his Cuban hilltop home; Woody Allen – the prototype hipster – who has written every word of his hefty half century of screenplays and novels on the same Olympia portable SM-3 typewriter. Hemingway said, “There is nothing to writing. You just sit down at a typewriter and bleed,” and there is something of that blind faith about the current attitude to the machine – a belief that what one writes with it is more profound, perhaps simply in its literal existence as ink on paper, but also maybe for the stentorian sounds of the machine that made it. Also, in its connection to great writers of yore; perhaps, through its use, the aspirant will receive some of their magic.

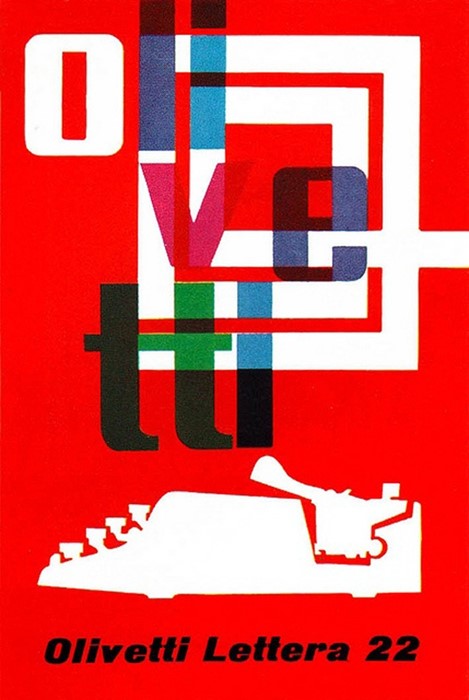

Films have done nothing to allay the romance or the prevalence of the machine. In 1960’s The Shining, Jack’s mental deterioration is revealed when his wife flips through the pages of his typewritten manuscript finding the phrase, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,” repeated ad infinitum. In Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Wolf delineates his drug-fuelled theories on the death of the American Dream on a red IBM Selectric. And in the latest installment of sepia tinted whimsy from Wes Anderson, his lovestruck heroes match each other for inconvenient running away luggage, taking both a record player and a portable typewriter. And beyond film, the late Anna Piaggi used an Olivetti Valentine up until her death this year, and AnOther Magazine Editor-In-Chief Jefferson Hack collects them. Essentially, it is clear, no matter what the factories say, we haven’t seen the last of the typewriter yet.

Text by Tish Wrigley