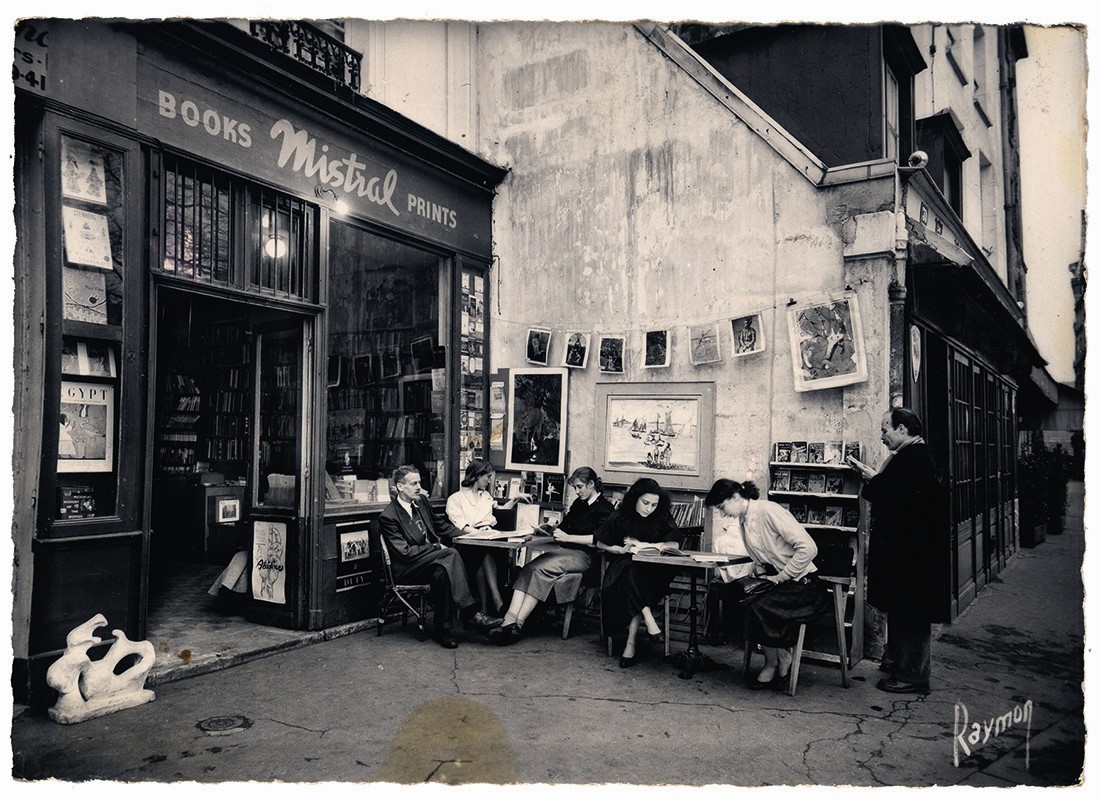

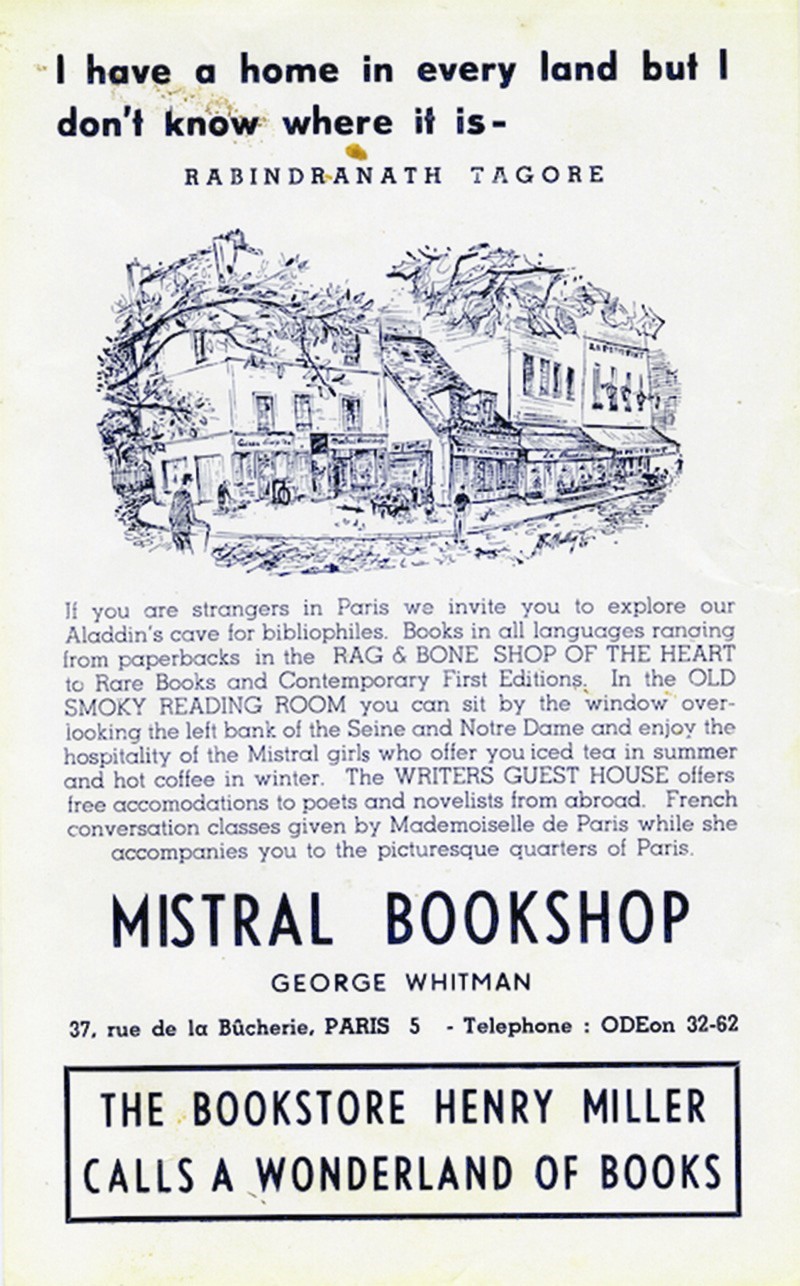

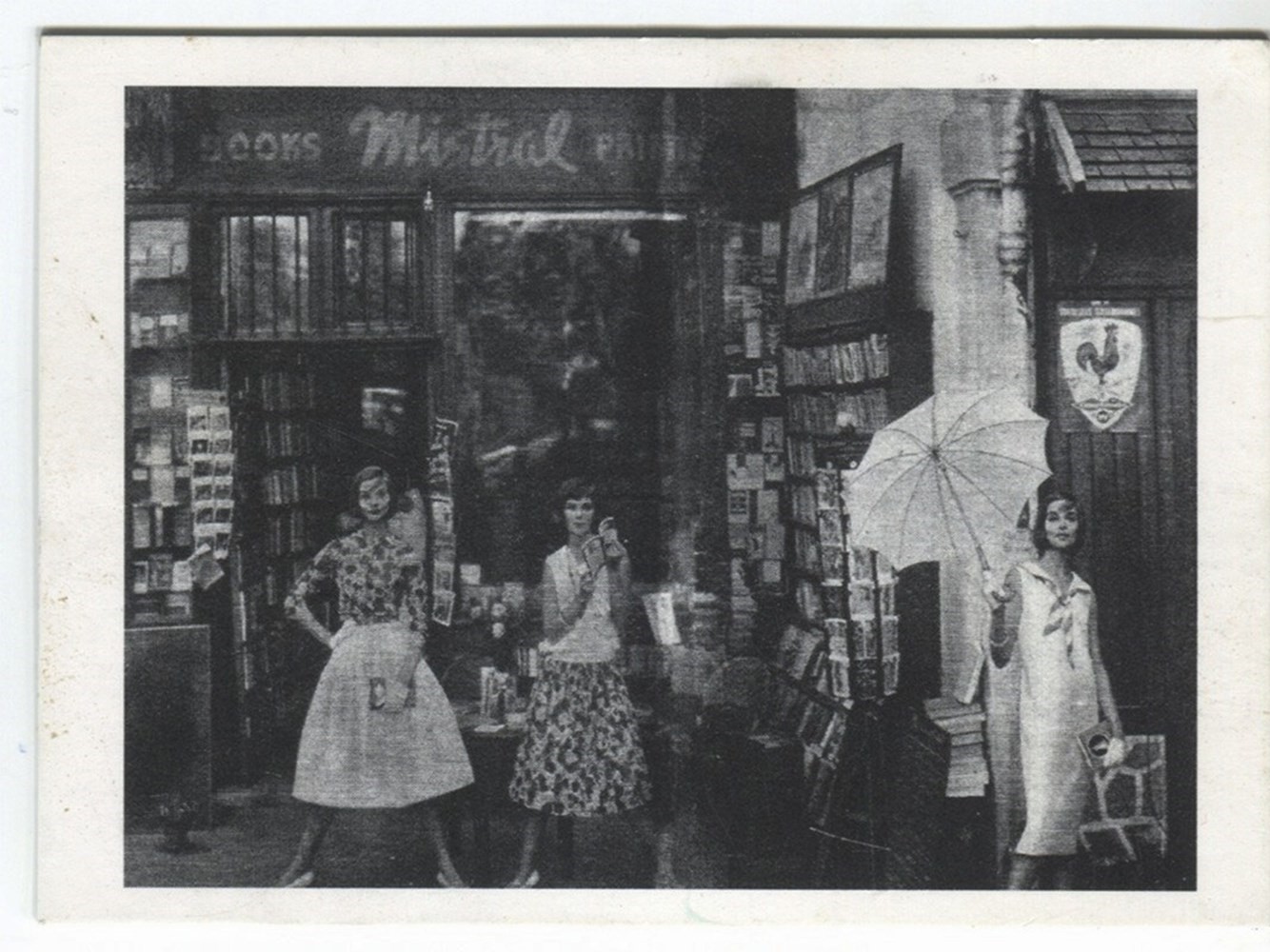

George Whitman opened his bookshop – first called Le Mistral, later renamed Shakespeare and Company – at 37 rue de la Bûcherie on August 14, 1951. It was a modest space, with no electricity and just three narrow, ground-floor rooms, set one after the other like railroad cars, each no more than 15 feet wide. The shop’s sole window faced out onto the River Seine and Notre-Dame Cathedral. Behind the store were all the marvels of the Latin Quarter.

“I’d long wanted a Parisian bookstore of my own,” said George. “After the second world war, there were innumerable shops for sale – France was in an economically bad situation – but I held off until I finally found the exact one of my dreams, the ideal location in the whole world."

A month prior, George had met an Algerian grocer while reading in a park near his residence, on Boulevard Saint Michel. The grocer was hoping to move his family to the country and was offering to sell his shop space for $500. “I almost didn’t take it when I learned that the building had been condemned,” he said. “But then I found out it had been condemned in 1870, so I decided to take a chance on its holding up for a few more decades.”

The war was barely over. France and its people were hard-hit and poor, Paris grey and rundown. The Latin Quarter was especially grim, “a slum, with street theatre, mountebanks, junkyards, grimy hotels, wine shops, little laundries, and tiny thread-and-needleshops,” as George described. It was populated by students, those who resided in the quartier’s small, dingy no-star hotels. They were joined by American G.I.s and the new bohemians – writers, artists, homosexuals, musicians, drug-users – who were flooding into Paris to take advantage of the weak franc and, as the decade progressed, a police force increasingly preoccupied by the Algerian fight for independence.

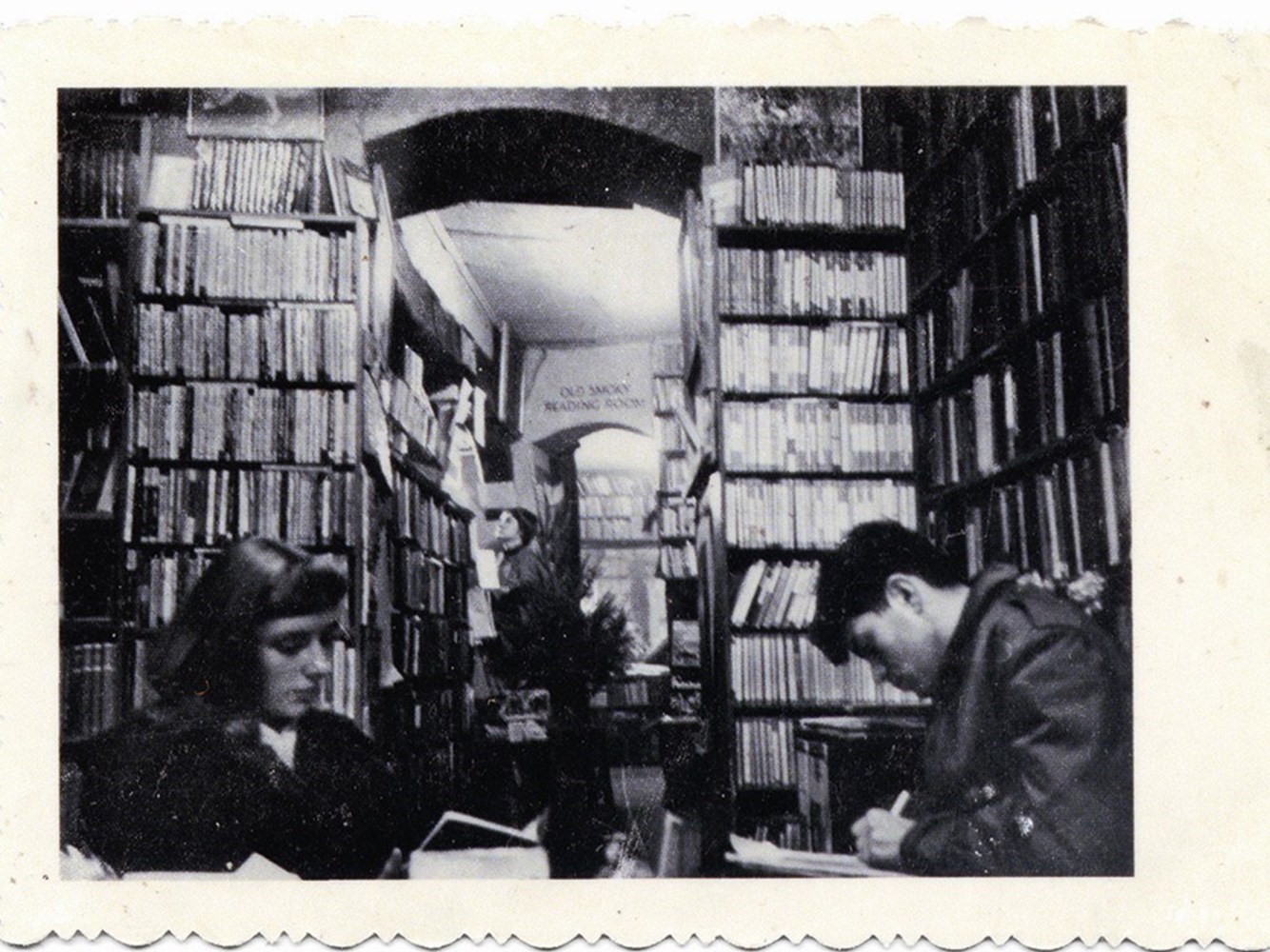

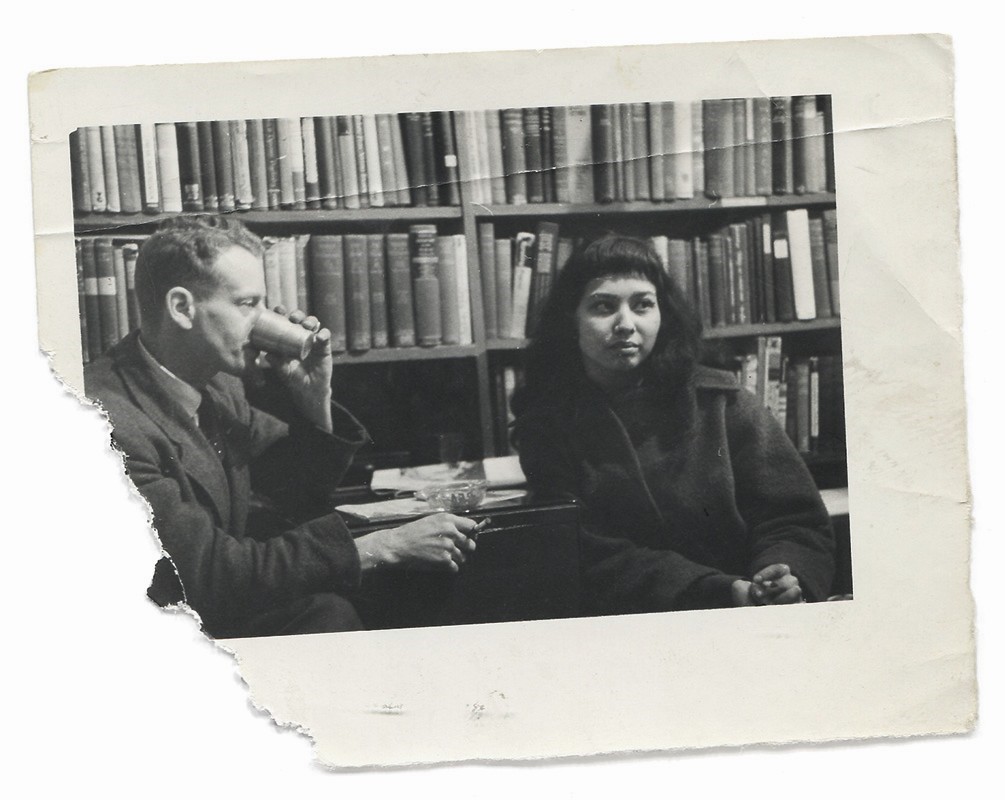

George’s bookshop had three rooms. The farthest one back was converted into a reading space and dubbed the Old Smoky Reading Room, the same name given to George’s former room at the Hôtel de Suez, presumably because there were no windows and many smokers. (George himself was known to light one cigarette after the next.) It was at the Hôtel de Suez that George had first encountered a young Sorbonne PhD student named Lawrence Ferling, who would later be known as Lawrence Ferlinghetti, co-founder of City Lights bookstore in San Francisco, the publisher of Howl, and one of America’s most celebrated poets. Ferlinghetti recalled meeting George: “When I was in Columbia University Graduate School, I used to see his sister, Mary, who was in the philosophy department and, while she was not exactly my girlfriend, I remember sitting with her in her front window as she told me about her brother George who had recently arrived in Paris after wandering the Orient and South America. I imagined this romantic wanderer, a kind of wayward Walt Whitman carrying Coleridge’s albatross. When I took off for Paris in late 1946 to go to the Sorbonne and get a doctorate, Mary gave me George’s address. It turned out that his albatross was books, and they had a passionate relationship. I found him in an airless, windowless hole-in-the-wall in the Hôtel de Suez, Boulevard Saint Michel, with books up to the ceiling on all walls, and himself the ghost of Stephen Dedalus cooking supper over a can of Sterno (or some other eternal flame of his own making). He was selling books out of his hotel room to American students on the G.I. Bill. He was already in the thrall of a kind of mistral bibliomania.”

The middle room of the bookshop was called The Blue Oyster Tearoom, despite its gold-coloured walls. It had a makeshift sofa that doubled as a bed at night. George slept here, though he was quick to give up the space for writers and artists in need. Soon this was more nights than not as word got around of a free place to stay in Paris. “The philosophy of the bookstore is to reciprocate the hospitality I received in the past, when I hoboed through the U.S., Mexico, and Central America,” said George. “I believe we’re all homeless wanderers in a way.” George called his guests “Tumbleweeds” after the rolling thistles that “drift in and out with the winds of chance”, as he said. In exchange for a bed or floor space, Tumbleweeds were asked to help out occasionally at the shop. By 1952, George had rented a studio apartment for himself and his dog, François Villon, around the corner, on rue Galande.

The shop’s front room, looking onto Notre-Dame, held a little alcohol stove on which George would fix meals for himself and his guests. Dinners were eaten by candlelight, surrounded by the small stock of books. Some of the titles were for sale; others could only be borrowed by a subscription to George’s library. There was a fee of a few francs, though George often waived it for writers, artists, and students.

In the spring of 1952, the avant-garde literary journal Merlin was founded out of the bookshop by a band of bohemians: publisher Jane Lougee and editors Alexander Trocchi, Christopher Logue, and Richard Seaver, among others. “They were a group of hoboes, a really creative group of young writers,” said George. “Jane was getting a little money from her father, who was a banker in Maine. With that money, she financed Merlin because she was in love with Trocchi. Jane was scrubbing floors to pay for food and lodging. Trocchi was very persuaded of his genius.” George gave the editors space for a little office, and they would sometimes stage readings in the bookshop. Merlin published Jean Genet, Eugène Ionesco, Jean-Paul Sartre, and a then-unknown Samuel Beckett, whom the journal is credited with having “discovered”. It was one of the first to publish him in English.

Established writers and artists frequented the bookshop: Julio Cortázar, Anaïs Nin, James Baldwin, Max Ernst, Dorothea Tanning, Richard Wright, William Saroyan, Terry Southern, and William Styron, along with editors from The Paris Review – Peter Matthiessen, Robert Silvers, and George Plimpton.

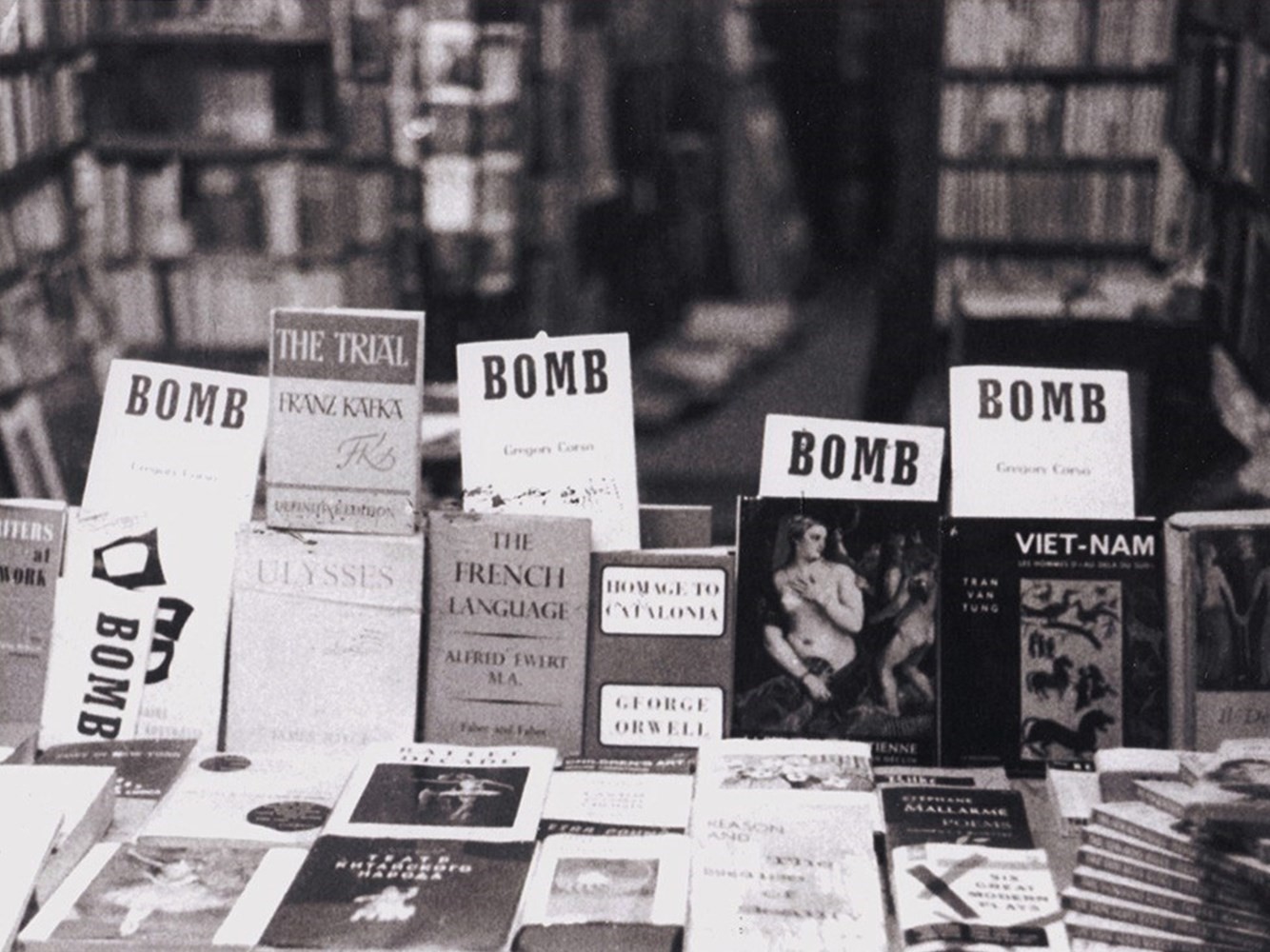

The Beats arrived in Paris in fall 1957. First came Gregory Corso, followed by Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, and William Burroughs. They lived a few streets away, at 9 rue Gît-le-Coeur, a ratty, no-name hotel renowned in bohemian circles for its cheap accommodations. Later, it would be referred to as the Beat Hotel. Its sympathetic proprietress, Madame Rachou, rented rooms to writers and artists, often letting them pay with artwork when they were low on cash. Anything went at the hotel – homosexual couplings, interracial relationships, loud music, drawings on the walls, drugs and drinking – anything but the overuse of costly electricity.

Corso spent a lot of time at the bookshop. On Christmas Day, 1957, for example, he passed the afternoon reading, writing, and enjoying George’s holiday fare: ice-cream, donuts, and Scotch. Burroughs regularly attended Sunday afternoon tea parties, though he often complained that he had no luck meeting available young men there. Occasionally, he’d consult the library’s medical section as he refined his work-in-progress Naked Lunch, which would be published in 1959 by Maurice Girodias’s Olympia Press, based in Paris. Ginsberg’s collection Howl and Other Poems had recently been published by Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights. After the collection’s debut, Ferlinghetti was arrested and charged with obscenity. While a judge eventually ruled that the poems were not obscene, the well-publicised trial brought fame to Ginsberg, who’d chosen to hide out abroad rather than endure the attention back in America.

Still, Ginsberg agreed to do a public reading of Howl at the bookshop, accompanied by Gregory Corso and a few other poets. On the afternoon of Sunday, April 13, 1958, crowds packed into the bookshop’s ground floor and spilled out onto its esplanade. The first poet to read was not an unequivocal success. Ginsberg and Corso personally objected to his work, calling it “uncommunicative junk”. To demonstrate what “real poetry” was, the two stripped naked to recite their poems. Two buff men purporting to be bodyguards flanked Corso as he read, and though Ginsberg was a bit drunk (he blamed his nerves) his Howl caused a sensation. Next, musician Ramblin’ Jack Elliott played songs and read from Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, which had recently been released. Burroughs had initially refused to participate, but once at the event, he was lured onto the stage by a young man, a bookshop regular, and gave what was said to be the first ever reading from Naked Lunch. “Nobody was sure what to make of it, whether to laugh or be sick. It was something quite remarkable,” said George.

This is an extract from Shakespeare and Company, Paris: The Rag & Bone Shop of the Heart, due out in autumn 2015.