From Andy Warhol to Marcel Duchamp we celebrate the highlights of the cult publishing wonder

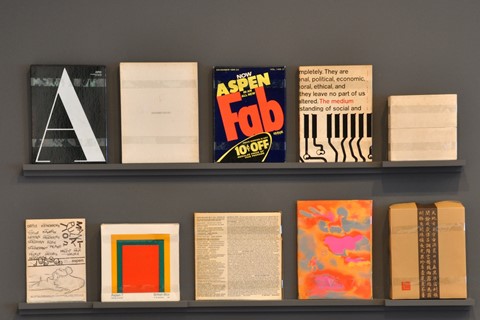

The first three-dimensional Magazine in a Box, Aspen was brought to life by Phyllis Johnson, a former editor at Women’s Wear Daily and Advertising Age, while on vacation in the ski resort town of Aspen, Colorado in 1965. Because it came in a box, as its publisher explained to subscribers in the first issue, the magazine didn’t need to be “restricted to a bunch of pages stapled together,” but could include anything from “blueprints, a bit of rock, wildflower seeds, tea samples” to “an opera libretti, old newspapers and jigsaw puzzles.” Published on an irregular schedule between 1965 and 1971 and issued in a laminated custom-made cardboard box filled with flyers, phonograph records, Super-8 films, prints and postcards, the concept behind Aspen’s avant-garde spirit was that of a multimedia magazine dedicated to covering “culture along with play”. As a response to the restrictive industry format, each issue was overseen by a different editor and designer and devoted to different topics – as its founder once said, it was conceived to become “a time capsule of a certain period, point of view or person”. With ten issues published over six years, Aspen’s life was short but culturally meaningful. Counting contributions by some of the most prolific artists of the century – including Peter Blake, Ossie Clark, Marcel Duchamp, David Hockney, John Lennon and Lou Reed – Aspen was a marvel of creative journalism. Due to the inconsistency between issues, the magazine was deprived of its second-class mail license and forced to fold by the US Postal Service in 1971. Few copies remain – back issues now sell for as much as $2,000 – but its impact on the publishing world shall not be forgotten, so here we pick our favourite moments from the cult magazine’s glorious history.

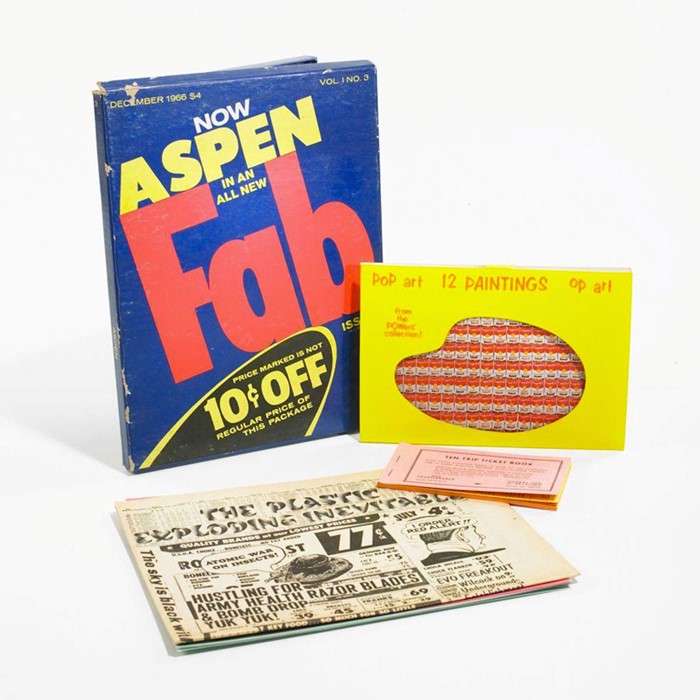

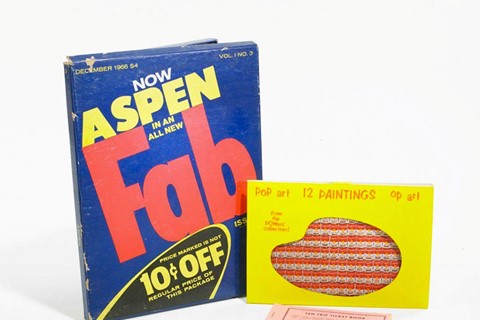

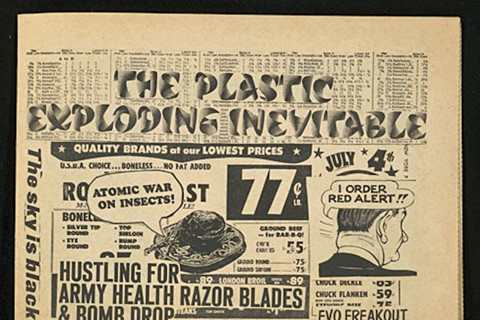

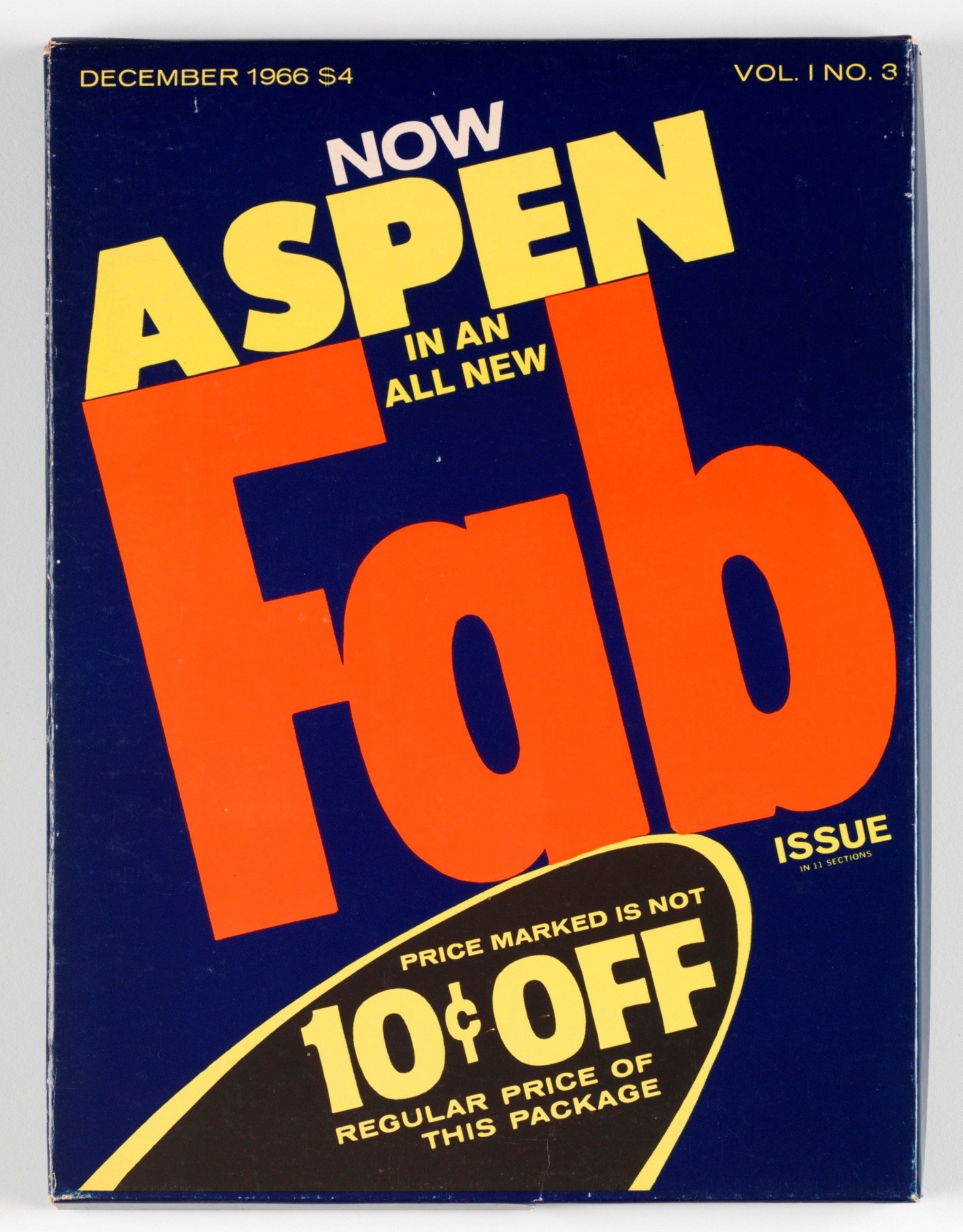

The Pop Art issue

Co-designed and edited by Andy Warhol and David Dalton, the legendary Pop Art issue was published in December 1966. Delivered in a Fab laundry detergent-inspired box, issue 3 was dedicated to 1960s New York City’s cultural scene. It included a folder with press and track material for Lou Reed’s Velvet Underground as well as music reviews. As opposed to the jazz and classical recordings of the previous issues, the pop art edition included a guitar flexi disc by John Cale of the Velvet Underground. While not so keen on advertising – the ads were hidden underneath the box or listed on a loose sheet at the bottom of the magazine – Aspen was an art director’s playground. Among the issue’s gems were 12 pop art painting reproductions from Thomas Powers’ art collection, including works by Roy Lichtenstein and William de Kooning, alongside two flip books based on Andy Warhol’s film Kiss and Jack Smith’s Buzzards Over Bagdad, a ten acid trips ticket book of extracts from a conference on LSD that took place in Berkeley that same year and a one-off copy of the Warhol Factory's one-shot underground paper The Plastic Exploding Inevitable.

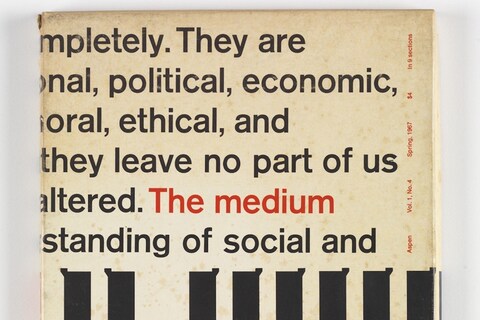

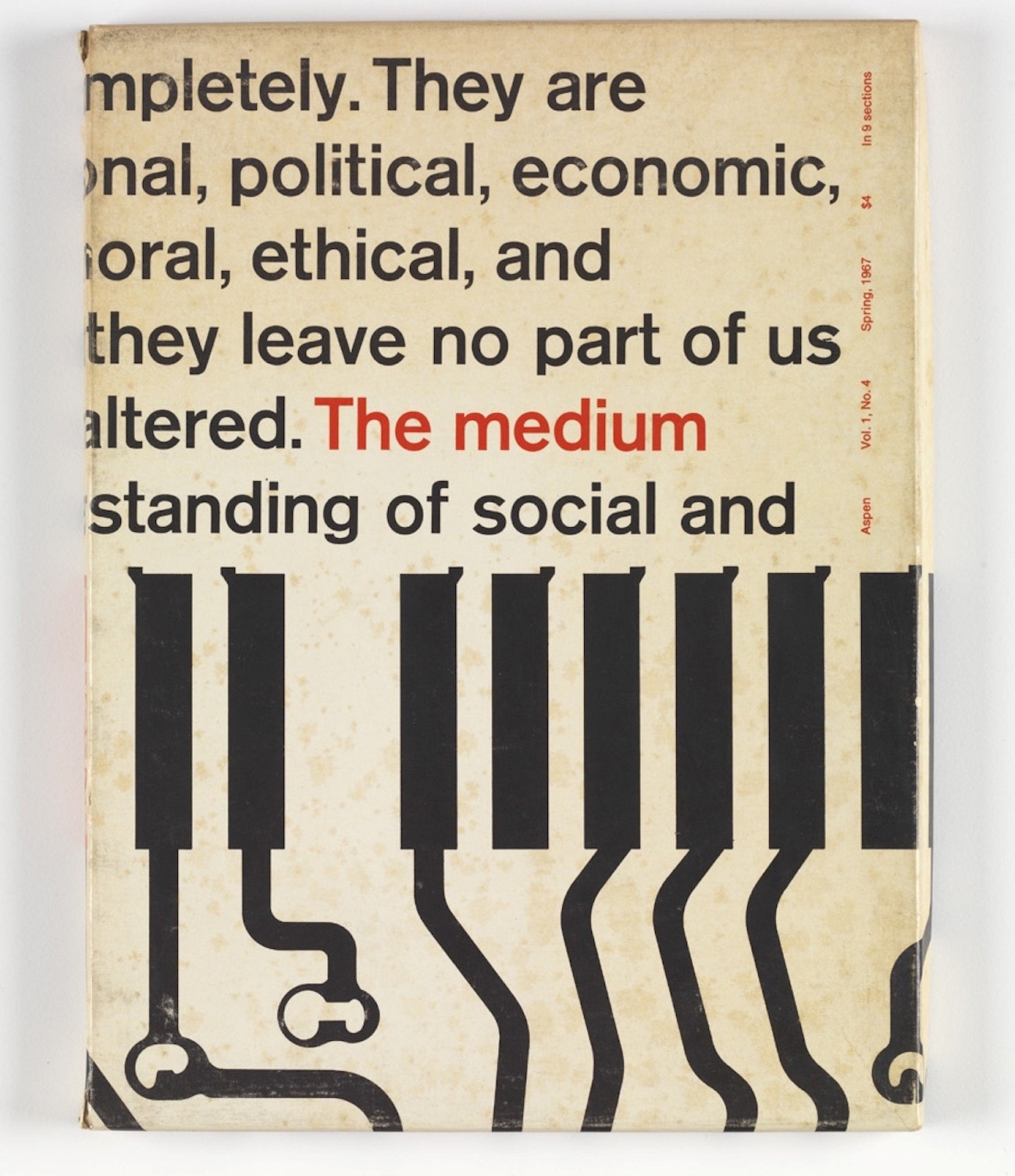

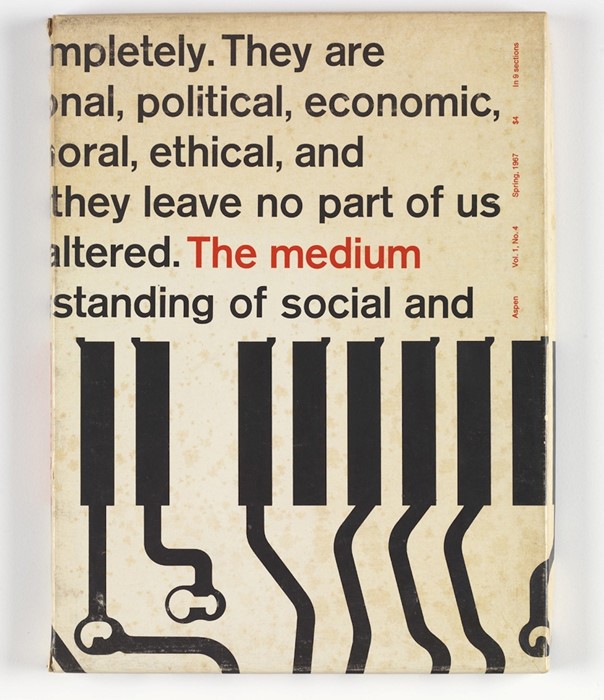

The McLuhan issue

Inspired by Canadian theorist Marshall McLuhan’s studies on the media society and illustrated by graphic designer Quentin Fiore with go-around-the-edge text and a circuit board, issue 4 was out in 1967. Introduced with a poster-size page collage of McLuhan’s book The Medium Is the Massage, the whole issue revolved around social themes like the TV generation and world improvement. Among the highlights were an essay on electronic music, a self-guiding experimental trail to the discovery of nature through the senses and a folder containing passages from Danny Lyon's book about the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club.

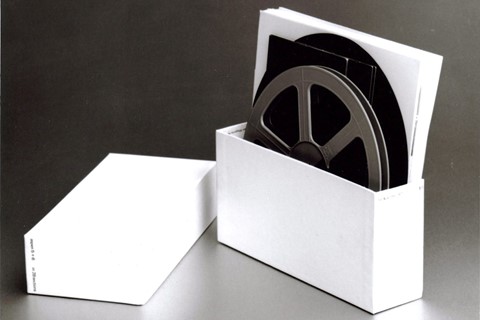

The Minimalism issue

Centered on conceptual, minimalist and postmodern art, issues 5 and 6 were combined in one big visionary edition. Guest-edited by artist and critic Brian O'Doherty and published in the winter of 1967, it saw David Dalton and Lynn Letterman collaborate on the art direction. Dedicated to Mallarmé and delivered in a two-piece white box containing 28 items, the Minimalism issue was about giving a participatory experience to the reader – contributions by artists such as Mel Bochner, Marcel Duchamp, Merce Cunningham, William S. Burroughs, John Cage and Morton Feldman came in the form of essays, films, sound recordings, music scores and DIY miniature cardboard sculptures.

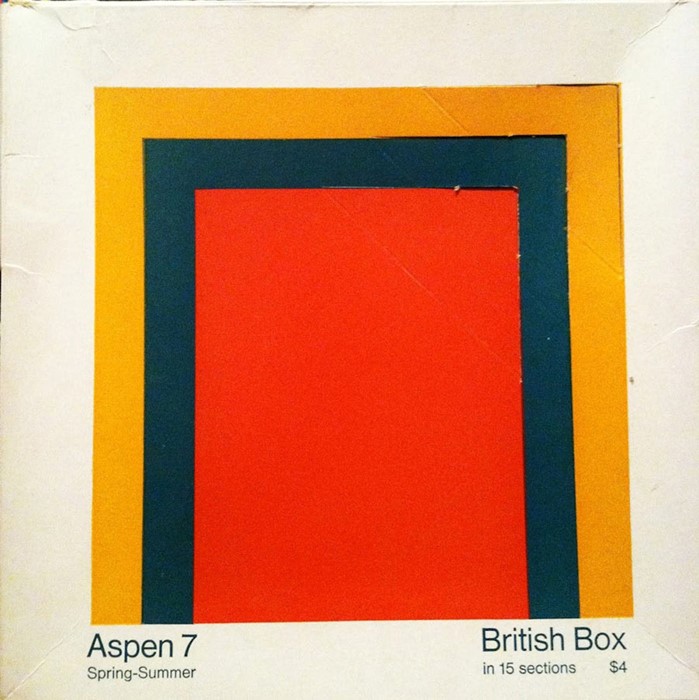

The British issue

To read the British issue must have felt like taking a Russian doll apart. A 1970 print exploration of the new British art and culture scenes, issue 7 once again provided the full Aspen experience. Contained in the box designed by Richard Smith was a sewing pattern for British Knickers by fashion designer Ossie Clark, alongside a collection of souvenirs found by pop artist Peter Blake, The Lennon Diary 1969 – a book of futuristic views by the Beatles legend – phonograph recordings by Yoko Ono and John Lennon and David Hockney’s series of drawings Notes On Rumpelstiltskin.

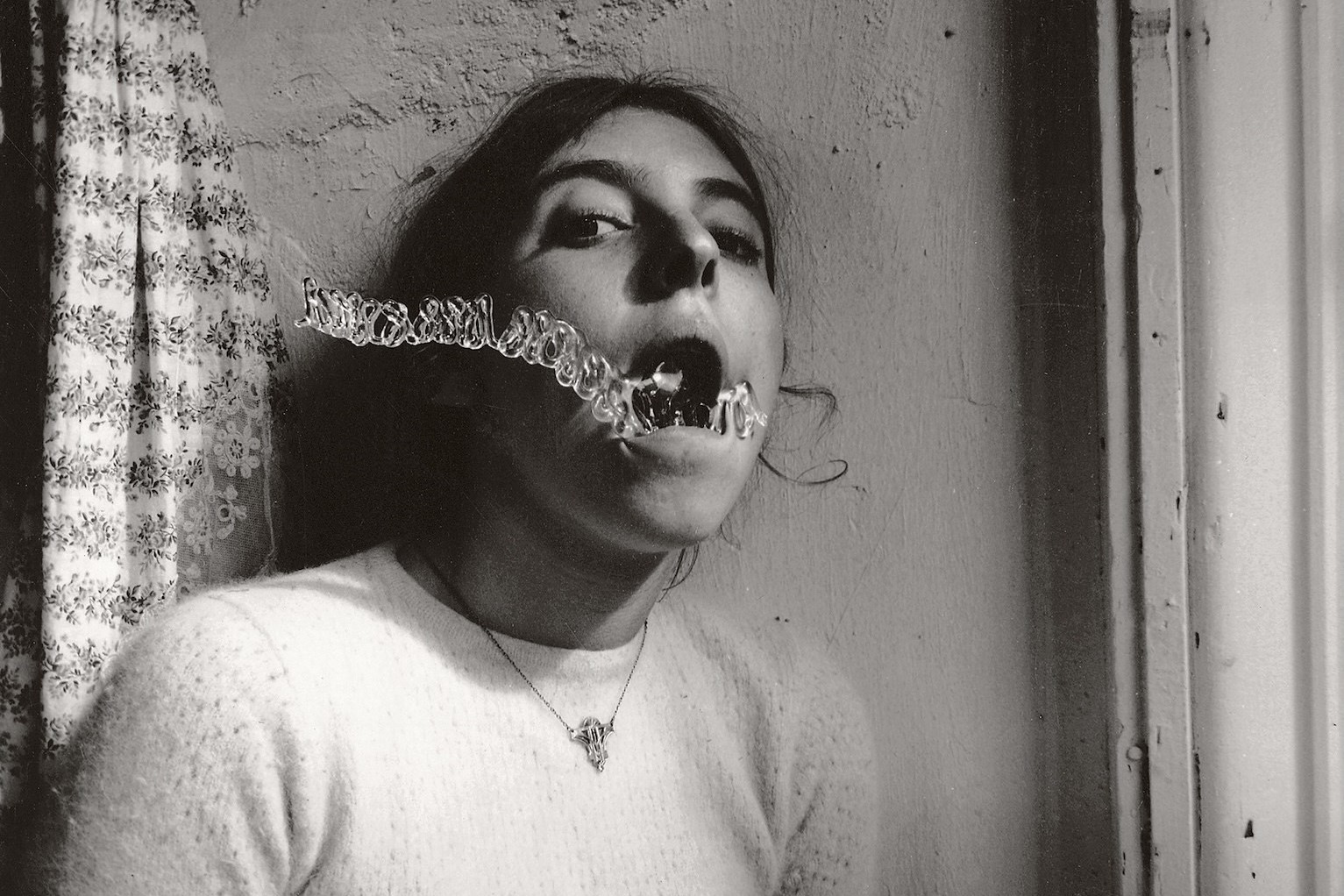

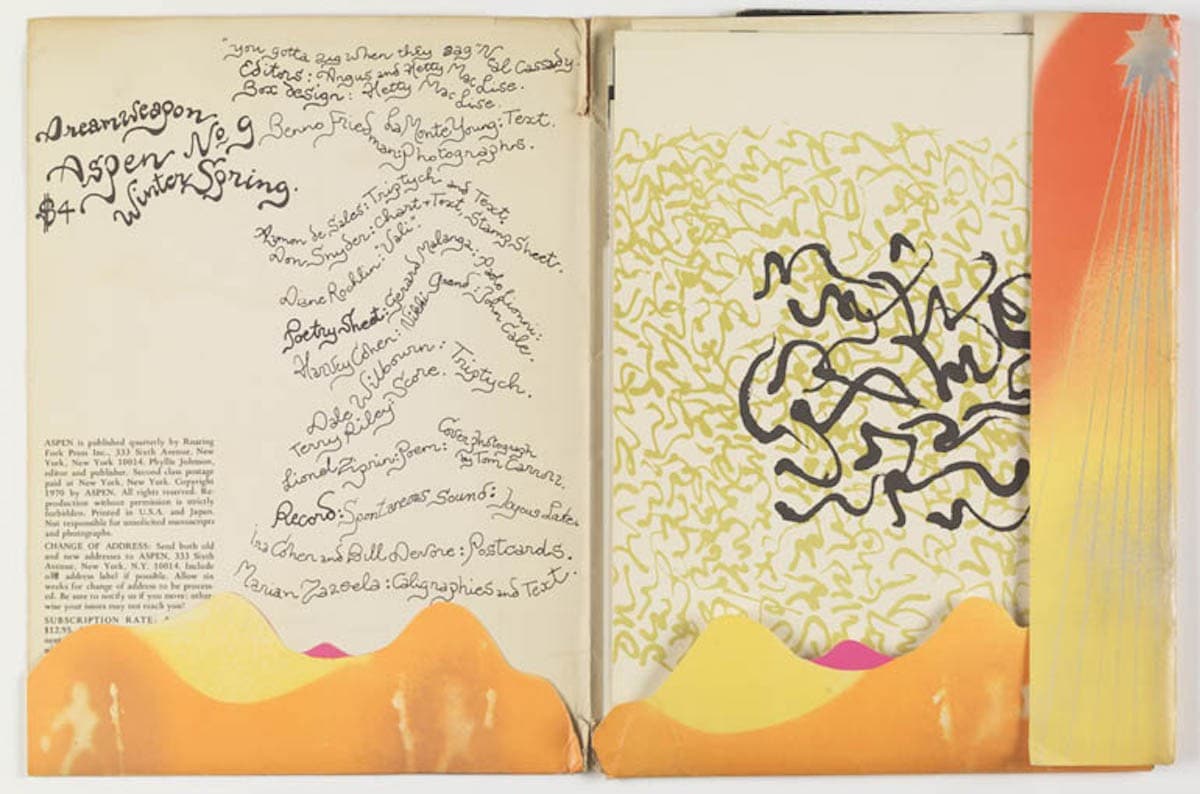

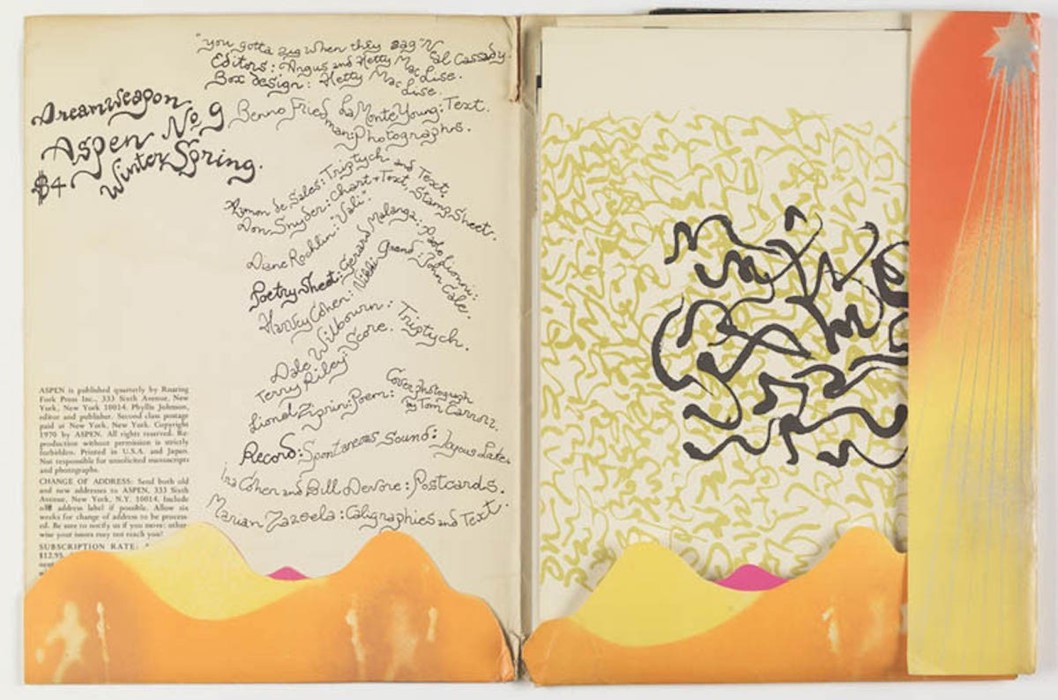

The Psychedelic Issue

Titled Dreamweapon, issue 9 was released in 1971 and was devoted to the art and literature during the psychedelic drug movement. It featured a hallucinogenic cover designed by Hetty MacLise who, together with husband and original Velvet Underground drummer Angus MacLise, also curated the design of the whole issue. Inspired by the acid trip tickets presented by Warhol in issue 3, Dreamweapon explored the wilderness of those years. From the words “Lucifer, Lucifer, Bringer of Light” printed on the back of the cover to Neal Cassady’s quote “You gotta zig when they zag” written on the inside of the box, the issue enclosed devilish images such as Dale Wilbourn’s drawing Triptych, alongside poems like Vali Myers’s letter to friends Diane and Shelley, accompanied by photographs by Diane Rochlin. Psychedelic influences in music were explored through spur-of-the-moment recordings like Spontaneous Sound and Aymon de Sales’ illustrated Musical Scores and Glyphs. Psychedelic art was also included in the form of Benno Friedman’s chemically stained frames from classic Western movies and Don Snyder’s Lumagraphs, a gummed stamp sheet of female nudes. Possibly the most fascinating of all, the Psychedelic issue surely scored the high point of Aspen’s implausible and boundless spirit.