We spotlight one of the most remarkable female pioneers of the 19th century

Julia Margaret Cameron is arguably the most influential British photographer you, quite possibly, may never have heard of. In her short 11-year career, she broke all the established rules of photography with a spirited conviction, freeing the medium from its rigid, Victorian constraints and carving out a trail for future photographic innovators.

Born in Calcutta in 1815, to Adeline de l'Etang and James Pattle, a British official of the East India Company, Cameron was considered the ugly duckling alongside her two, strikingly beautiful sisters. But what she lacked in looks, she made up for in originality, intelligence and charm. As her great-niece Virginia Woolf wrote in 1926, "In the trio [of sisters] where...[one] was Beauty; and [one] Dash; Mrs. Cameron was undoubtedly Talent." This talent soon caught the attention of one Charles Hay Cameron, a member of the Law Commission stationed in Calcutta, who was 20-years Cameron's senior, and the pair married in 1938, going on to raise six children and adopting six more.

A devoted mother, it wasn't until the age of 48, when she was given a camera by her daughter Julia, that Cameron took her first photograph, igniting the passion that would come to define her. Here, to mark her bicentenary, and the opening of a new show of her works at the Science Museum, we present a five-point guide to her pioneering approach and lasting legacy.

1. She was undeterred by limitations of gender

Photography, as with most fields in Victorian Britain, was overwhelmingly male dominated, not least because the physical demand of handling large camera equipment, and the potential hazards of working with dangerous chemicals, went against the era's expectation that women should be demure and dainty above all else. But Cameron was a force to be reckoned with – ambitious and free-spirited, she was utterly devoted to her cause from the very outset, frequently to be found with hands dripping with development fluids, rushing about her house, Dimbola Lodge, on the Isle of Wight. She was also fascinated and undaunted by emerging techniques, quickly embracing the far superior but extremely fiddly wet-collodion process – invented in 1850 by Frederick Scott Archer – which would become her favoured method.

2. She refused to adhere to static, Victorian photographic conventions

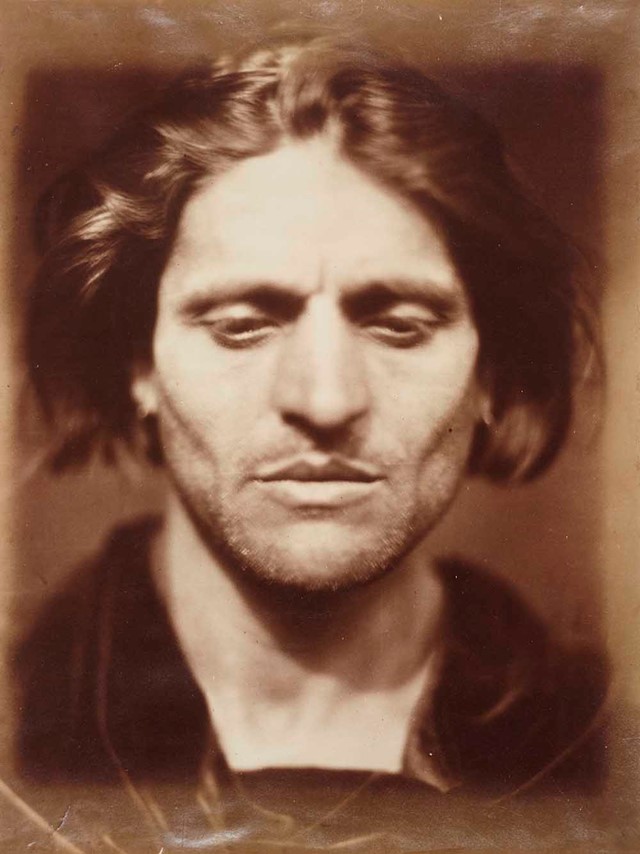

As if Cameron's "impertinent" assumption that she could master a man's pursuit wasn't enough, she further riled photography critics with her highly progressive approach to form and composition. In the case of most Victorian photography – fixed, traditonally posed, set against a formal backdrop – it takes a mere glance to identify the rather stuffy period it represents. Not so with Cameron's beguiling works, which are remarkably modern in their close-up examination of subjects' faces, their minimalistic backdrops and their hazy, almost spectral lack of focus. She was also unusually accepting of chemical glitches, refusing to abandon photographs because of smudges and discoloured patches. These idiosyncratic qualities provoked widespread outrage, with the Photographic News declaring, “What in the name of all the nitrate of silver that ever turned white into black did call this good photography... smudged, torn, undefined and in some cases unreadable?” Nowadays however, they have secured Cameron's place as a modernist trailblazer.

3. She assumed the role of director, allowing her imagination to guide her

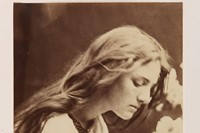

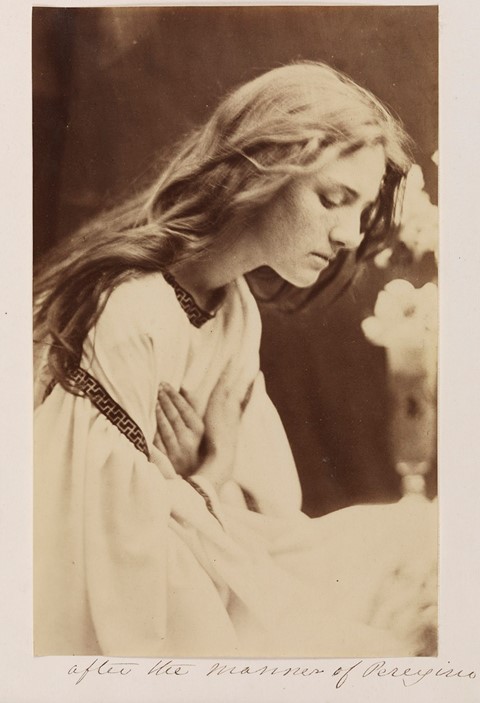

An extremely prolific and enthusiastic creative force, Cameron never shied away from a photo opportunity. She was an extremely sociable character, always surrounding herself with family and friends whom she would frequently entice into acting as her subjects. As well as taking straightforward portraits, Cameron loved literature and poetry, and often reinterpreted scenes from famous texts in her photographs – be it Shakespeare, Tennyson or Biblical scenes. These shots are breathtakingly evocative and dramatic, especially considering that very few of her subjects were professional models. As Tim Clark, co-curator of the Science Museum exhibit explains, "You get this sense of Cameron being a consummate stage director with these constructed scenes. I think we can consider her in a really contemporary light, akin to Cindy Sherman and Jeff Wall."

4. She pre-empted the age of celebrity

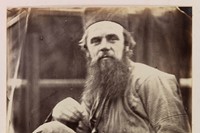

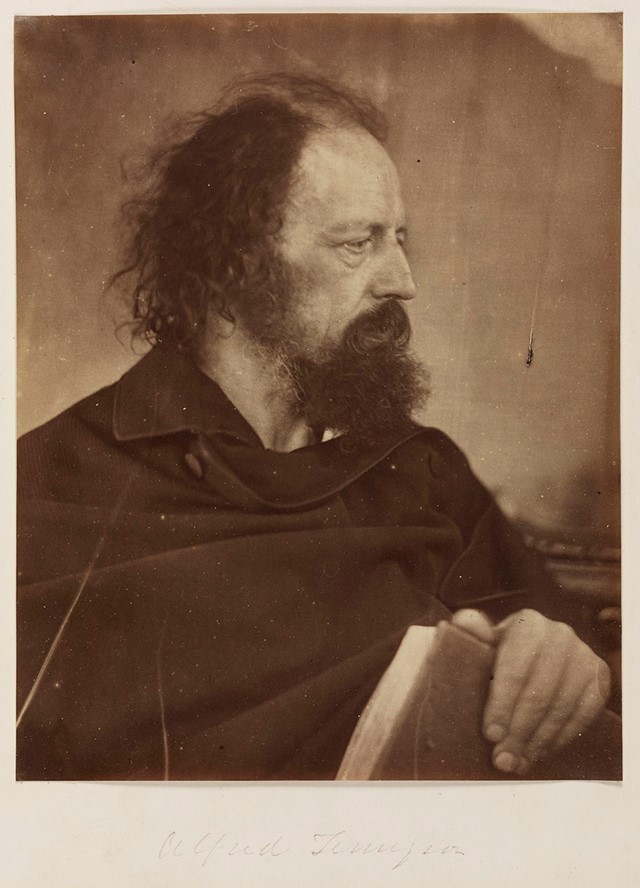

Cameron is perhaps most commonly known for her portraits of the many eminent figures she counted among her friends. She was fascinated by the notion of celebrity – again demonstrating her forward-looking approach – and many of her works are the only photographic portraits that exist of these personalities. Alfred Lord Tennyson, poet laureate and Victorian icon, was a close friend of Cameron's, occupying the next door house to hers on the Isle of Wight. She took countless photographs of the billowing-haired, shaggy-bearded poet, perfectly capturing his noble yet dishevelled countenance; as well as lensing many of his famous friends, from Pre-Raphaelite painter Holman Hunt to novelist Anthony Trollope.

5. She fought for photography to considered to an art form, and succeeded

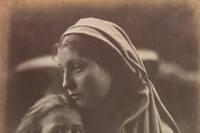

Throughout her career, Cameron was driven by the determination to see photography accepted as an elevated art form, alongside painting and sculpture. Her composition and styling often reference art history, like her variety of virgin and child scenes, which are notably sculptural in their portrayal of drapery and as moving as paintings in their expressive nature. Likewise her portrayal of fictional and allegorical scenes demonstrate photography's power to match traditional media across different genres.

Amazingly, this dream was realised, posthumously, thanks to Cameron's accomplished album, the Herschel Album, around whose 94 prints the Science Museum's exhibition is focussed. In 1974, Sam Wagstaff, a prominent photography collector and partner of Robert Mapplethorpe, bought the Herschel Album at Sotheby’s for £52,000 (an unprecedented amount in those days.) This prompted public dismay and, for the first time in the history of British photography, a passionate campaign was started to keep the album in British possession. It worked, and the collection was saved, signalling the first official recognition of photography as a serious art form and, in the words of Banks, "vindicating prosperously all the aspirations that Julia Margaret Cameron had."

Julia Margaret Cameron: Influence and Intimacy is at The Science Museum until March 28, 2016.