Laura Allsop considers the East Village artist and muse who captured her era with fantastical characters made out of fabric and wire

Every year on his birthday, designer Paul Monroe mysteriously receives a long-lost doll made by his late wife, the artist Greer Lankton. “This has been going on for the past five or six years. I’ll be searching for something, but then it just arrives on that exact day. She is totally fuelling this,” he says, referring to the recent revival of interest in her work, almost 20 years after her death. Monroe has been building up the Greer Lankton Archives Museum (GLAM) for the last 12 years, gathering missing pieces from far afield and garnering long-overdue attention for her beautiful and painstakingly created works.

Lankton, who endured a difficult gender transition aged 21, would be enjoying the spotlight, says Monroe. In her 1980s East Village heyday, ethereally pretty and with a penchant for bell dresses, stockings and Mary Janes, she captivated some of the era’s defining talents, among them the photographers Nan Goldin (who also shot the couple’s wedding photos), Peter Hujar, Steven Meisel, David Armstrong, and the artist David Wojnarowicz. “She had that kind of Edie Sedgwick energy. Everyone wanted to be around her,” says Monroe.

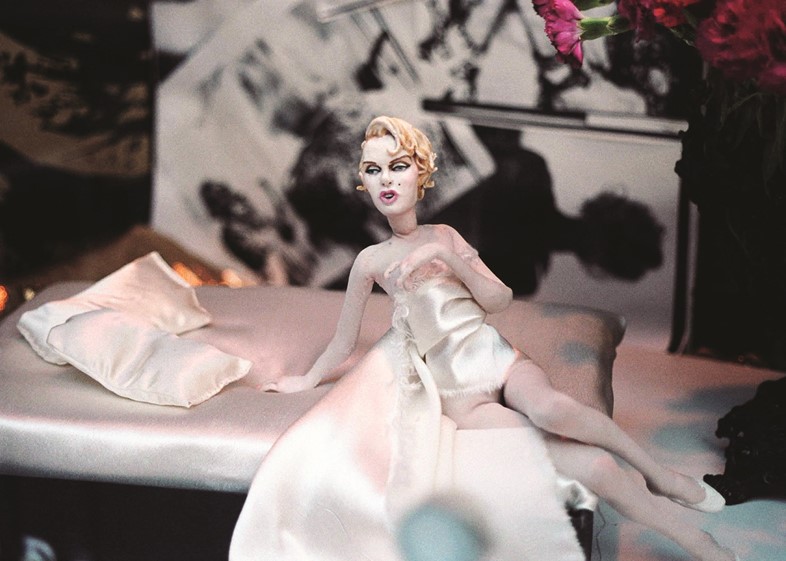

Her own work was fascinating, an extension of her lifelong exploration of – and embattled relationship with – the body. (Lankton suffered from anorexia for much of her life.) The dolls made up an alternate family, a gaggle of personalities constructed from tights, wire and plaster; real hair; and glass eyes from the taxidermist’s. She had been making them since she was a ten-year-old-boy growing up in the Midwest. Whether tastefully styled or denuded, attenuated or fleshy, her dolls – of drag queens, counter-cultural idols, brittle metropolitan doyennes, hermaphrodites and even herself – held court at Einsteins, the East 7th Street boutique run by Monroe, whose clients included Andy Warhol and Diana Vreeland. (One of Lankton’s best-known works is a life-size doll of the legendary Vogue editor, commissioned for a window at Barneys.) Far removed from the brash beauty standards of the day, they were fringe-dwellers like Lankton herself and she was forever transforming them. She told Dylan Jones in a 1985 interview: “Oh I love Barbie, but I think she’s gotten really bad… She’s so suburban now.”

Monroe and Lankton enjoyed a special creative partnership, but after their circle was ravaged by AIDS, the couple separated and Lankton moved to Chicago. Her last major work was a recreation of her tiny apartment for the Mattress Factory art museum in Pittsburgh. On permanent display, this fairy-lit jewelbox is populated by figures of various shapes and sizes, with shrines, busts and other ephemera, though the eye is inevitably drawn to the bald, emaciated figure lying in bed, wearing an expression of exquisite suffering and surrounded by bottles of pills. Lankton died of an overdose shortly afterwards and much of her work was scattered; Monroe is working hard to retrieve it.

Though acclaimed in her time by perceptive insiders, it is only recently that her startling work has begun to attract a wider audience. A retrospective last year at the Lower East Side gallery, Participant, Inc, close to where the couple spent their brightest years, drew a clutch of new admirers, including Wolfgang Tillmans, who brought most of the exhibition over to his Berlin gallery, Between Bridges, in the spring.

Right now, Monroe is busy preparing for their 30th wedding anniversary: 2017 sees a book, a museum show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington and a HBO documentary, produced by Lena Dunham, who vividly remembers seeing Lankton’s work as a child at the 1995 Whitney Biennial. “I think Greer’s conflicted emotions about transitioning helped make her work just so emotionally resonant,” says Dunham. “We all feel that sense of being lost in and betrayed by our own bodies. She made it into poetry.”

This article originally appeared in the A/W15 edition of AnOther Magazine.