A new exhibition exposes the extraordinary work of the Colombian photographer: haunting, experimental studies in light and shade

Who? Fernell Franco is one of Latin American photography's most prolific pioneers. Yet, he remains relatively unknown in Europe, with the first extensive European retrospective of his work opening at the Fondation Cartier in Paris later this week. Born in 1946, in the small hillside town of Versalles, as a small boy Franco and his family were forced to relocate to the city of Cali in southwestern Colombia, along with thousands of others fleeing the bipartisan violence that raged throughout the country at that time. This dramatic change of scenery made a lasting impact on Franco, who once observed, "In the countryside at night, there is the spectacle of stars in the sky. What I saw in contrast when I arrived in Cali were that the stars were on earth."

Franco found his way into photography at the age of 15, when he was employed as bike courier for a Cali-based photographic studio. A keen flaneur, he soon expressed an interest in getting behind the lens himself and was promoted to the role of fotocinero, enlisted to photograph everyday street scenes around the city. He was a natural, his unique exploration of light and shade and his gift for capturing the magic of the mundane setting him apart from his contemporaries, and by 1962 he had been hired as a photojournalist for El País and Diario Occidente.

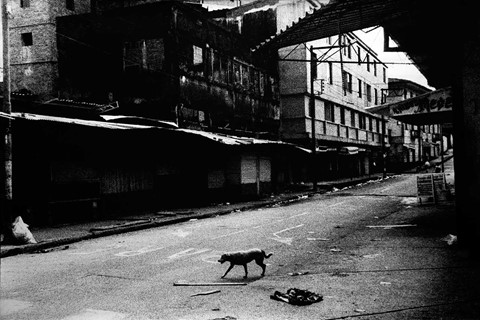

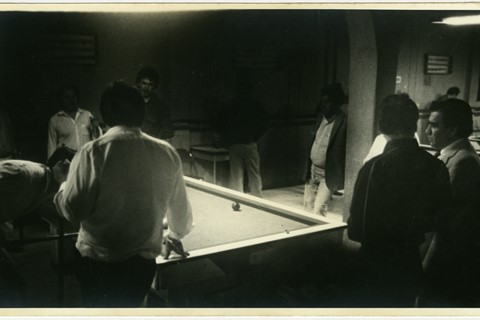

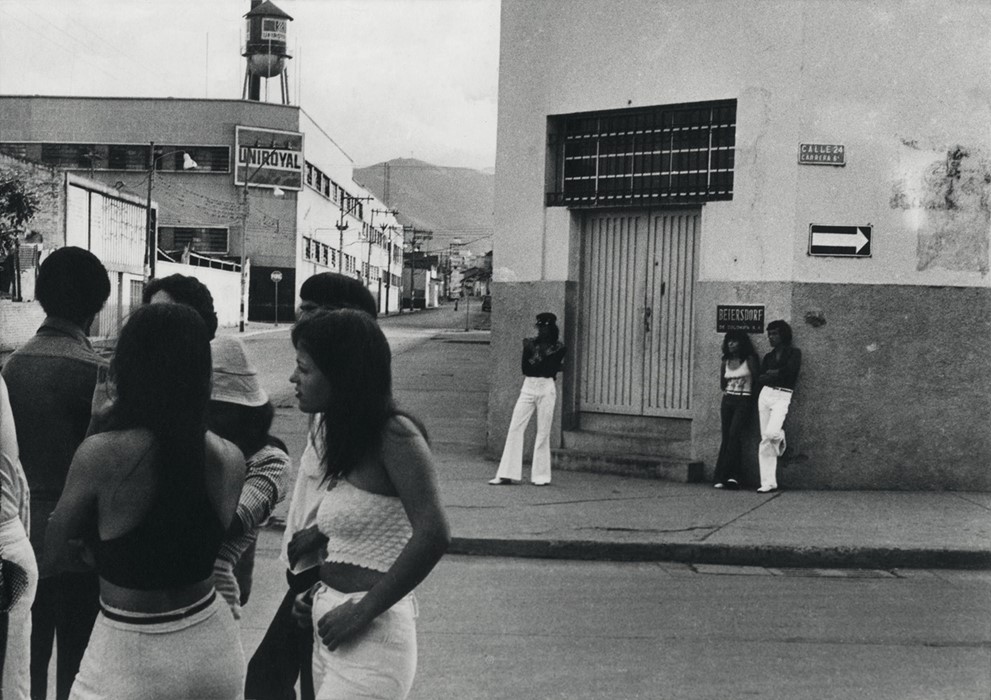

What? Later Franco would go on to work as a fashion and advertising photographer but in spite of this influx of commercial work, it was always through photojournalism that the photographer found the greatest freedom of expression. "I was searching for common things," he said, "things that took place in the city on a daily basis, that happened in the lives of normal people." Of course, in what was a period of intense industrial modernisation in Colombia, the scope of everyday experience varied greatly – from the violence, drugs and prostitution that permeated the city's dark underbelly through to the sparkling cocktail parties of the upper echelons; and Franco wanted to document it all.

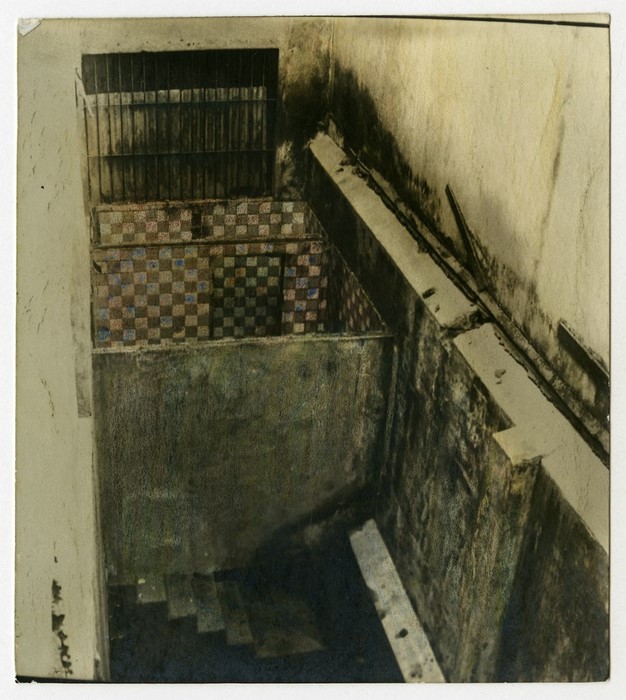

He was not alone in his fascination with urban themes; in the 1970s, Cali's art scene was positively blossoming and the photographer soon fell in with a group of similarly minded creatives, including writer Andrés Caicedo, filmmakers Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo and artist Oscar Muñoz, all united by their interest in popular culture. Muñoz – who has created a specially commissioned tribute to Franco for the Fondation Cartier's exhibit – explains, "I shared with Fernell Franco, and also with Ever Astudillo, a passion for the city at that time. The three of us used black and white, light and shadow, in a highly realistic figurative style, each one with his own poetic tone. We were fascinated by interiors and boarding houses, and later by the city in decline, its ruins, violence, and collapse."

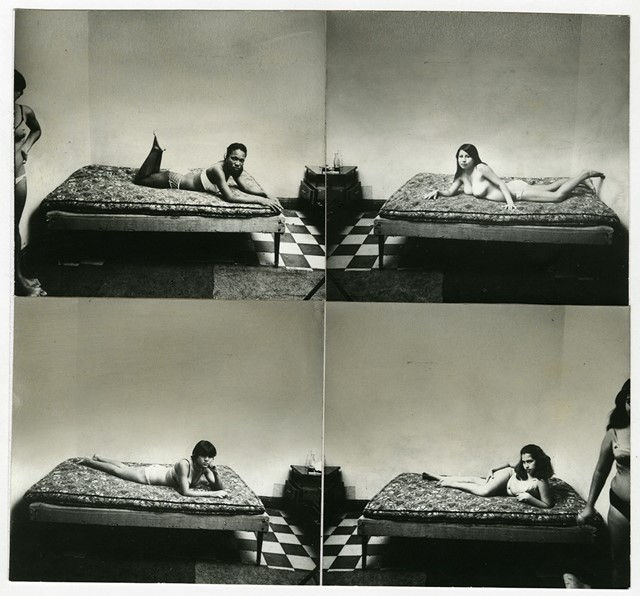

Indeed, many of Franco's most arresting works offer views of majestically crumbling interiors and streets littered with people and detritus, always rendered with striking levels of chiaroscuro influenced by the photographer's love of Italian Neorealism and film noir. Cinema also inspired Franco to create a sense of narrative in his pictures, which he often achieved through experimental formatting. This is perhaps most apparent in his series Prostitutes (1970-72) where for one work he arranged four images of different girls, stretched suggestively over the same floral mattress, into a single montage; while in another he hand-tore copies of the same portrait, processed to varying degrees, and pasted them together to create a haunting composition that finishes with the woman's white face floating against a totally black background. This unusual approach to development was also typical of Franco's idiosyncratic practice – as curator María Wills Londoño explains, he frequently sought to "revert the traditional processes of the image by eschewing chemical fixing agents, allowing his photos to remain 'alive', [and] manipulated lighting effects in the darkroom."

Why? While Franco (who died in 2006) was certainly a key documentarian of Colombia's history, his works offering extraordinary insight into the zeitgeist of an age that saw huge political, cultural, and structural changes, it was his progressive approach to his chosen medium that truly broke the mould. And it is this that the Fondation Cartier's exhibition seeks to highlight and explore through its display of 140 of the photographer's remarkably original and atmospheric images. As Wills Londoño summarises, "Franco’s highly experimental, pioneering work crossed the limits between media at a crucial moment in the history of photography, transcending the paradigm of photography as a documentary element and the photographer as merely a documentary agent."

Fernell Franco: Cali Clair-Obscur is at Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain from February 6 - June 5, 2016.