As a new exhibition exploring the artist's far-reaching influence opens at London's V&A museum, AnOther reveals some lesser-known facts about the pioneer of the early Renaissance

“If Botticelli were alive now he’d be working for Vogue,” actor Peter Ustinov once remarked – and indeed the early Renaissance painter’s forward-thinking ideas about beauty and technique might have served him better in the present day than they did when he was working. In spite of some 300 years spent in the shadows however, Botticelli’s great works have permeated every corner of pop culture since he was rediscovered by the pre-Raphaelites in the mid-19th century – and a new exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum is keen to explore them all. Here, AnOther illuminates ten facts about the great artist, from his secret love to his interstellar influence.

1. He was popular, and then unpopular (for 300 years) and then popular again

Sandro Botticelli, also known as Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi, was born into a modest family in Florence in 1445, and trained as a goldsmith before entering into an apprenticeship to become a painter. He quickly developed a keen eye for the bold outlines, intricate detail and a two-dimensionality which has become innately linked to his work in recent centuries, and he achieved success under the patronage of the Medici family. As Florentine culture took a turn for religious devotion in the late 15th century, however, Botticelli’s painterly style followed, and the years following his death in 1510 at the age of 64, his reputation faded.

It wasn’t until the birth of the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood in the mid-19th century that he returned to popular consciousness; English essayist Walter Pater created a literary work dedicated to him in 1870, and painters Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais and the like began adopting elements of his style, which had been deemed too crude and sentimental by Botticelli’s contemporaries, to use in their own work.

This resurgence of feeling for the painter sparked a new way of reconsidering old artists, judging their work on modern tastes rather than those which had been popular in their lifetimes, and a fascination with Botticelli’s oeuvre has continued ever since. Nowadays, he is considered one of the most important practitioners of the early 20th century, and a pioneer of the early Renaissance.

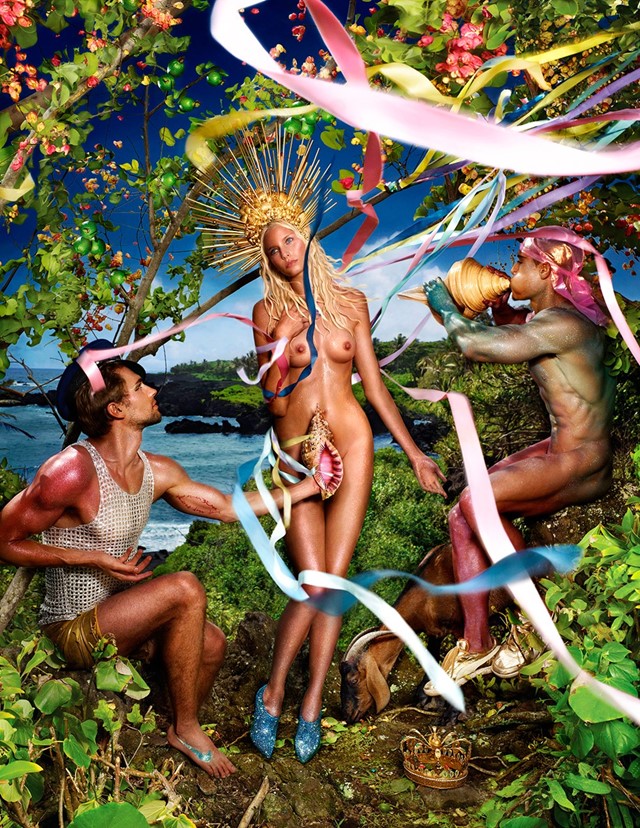

2. He certainly didn't shy away from yonic imagery

Ostensibly the most famous painting created in Botticelli’s lifetime, The Birth of Venus, which was probably commissioned by the Medici and painted between 1482 and 1485, has come to be viewed as one of the most famous works of art in the world. The painting represents Venus, the goddess of love, arriving on the seashore, modestly covering herself as a nymph approaches to clothe her.

The image was groundbreaking, not least because classical Venus stands beautiful and proud in a time when Christian tradition meant that most female subjects in artworks were depicted demurely poring over the figure of Jesus Christ. Poignantly, she also balances carefully in a seashell, a yonic symbol of love and fertility which had been an allegorical representation of the vulva since the middle ages, and which crops up repeatedly in his work, from Venus' beachy shores to sketchbook drawings. French artist Alain Jacquet took the shell reference in a different direction: his Camouflage Botticelli works depict the beauty as a Petrol pump, in a vibrant palette of pastel colours and recognisable logos.

3. Many believed he was deeply in love with his Venus

Botticelli never married, and once famously proclaimed that the idea of doing so gave him nightmares. Nonetheless, historical rumour mills never cease to suggest that he might have been in love with the model who stood for Venus in the famous work, who history believes was Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci, an Italian noblewoman from Genoa. The match is a logical one – it is commonly believed that Lorenzo, of the Medici family which commissioned the painting, was deeply in love with her – so it follows that Botticelli himself might have fallen for her, too, in the process of creating the work. He requested to be buried at her feet in the Church of Ognissanti on his death – a wish which was fulfilled when he died in 1510.

Some rumours, on the other hand, suggest that Botticelli’s aversion to the idea of marriage was due less to his unrequited love for Vespucci, than to his homosexuality – a 1502 entry claims that he ‘“kept a boy.”

4. His work is testament to the theory that ‘imitation is the greatest form of flattery’

Perhaps even more fascinating than Botticelli’s own work are the myriad ways his message resonates throughout art history – from William Morris’ tapestries replicating his figures, or utilising floral details from his magnificent Primavera, to mural painter Rip Cronk’s expansive work Venus on the Half Shell, which shows the beauty in thigh high leg warmers, hot-pants and roller skates, in the California tradition, towering over LA’s Venice Beach, which was painted in 1983.

5. He loved to 'modify' the female form

Botticelli’s depictions of female subjects in his paintings are considered by some to be one of the first examples of ‘Photoshop’, so to speak – he favoured archetypal beauty ideals over realistic portrayals, and as such he tended to lengthen his models’ arms, narrow shoulders, and pose them in such positions that would be impossible to sustain, were they real, thereby perpetuating an innately masculine idea of beauty and the female form.

6. Which, in turn, leaves him open to many a feminist reinterpretation

Forward-thinking though these ‘modifications’ of the female anatomy were, they also leave the early Renaissance artist open to many a feminist reinterpretation. Artists from Cindy Sherman to Joel-Peter Witkin have placed these ideas under close scrutiny – the former with a photographic self-portrait in a haunting mask, pinching the nipple of a false breast between two fingers, and the latter with a striking black and white photograph of the beauty, in which Venus is modelled by a hermaphrodite.

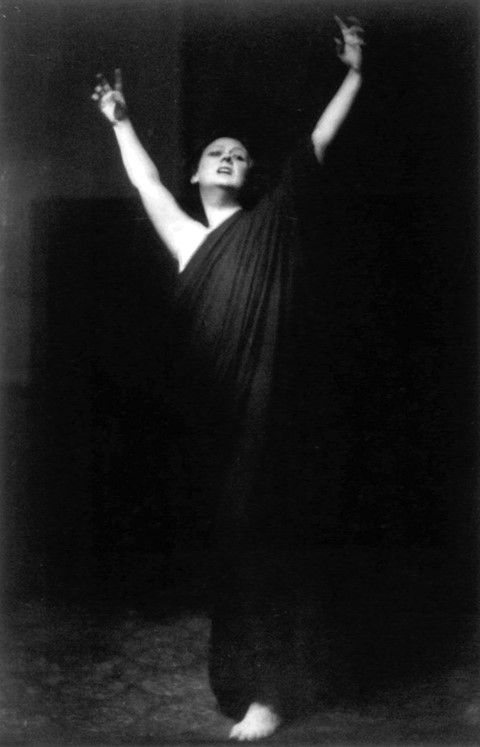

7. Isadora Duncan considered the artist one of her greatest influences

So inspired was American dancer Isadora Duncan by Botticelli’s Primavera, or the Allegory of Spring – sources state that as a child growing up in the late 19th century, the only picture she had hanging in her room was a poster of the piece, and as a result it would inform what she considered to be the height of beauty – that she decided to choreograph a routine in its honour. A film of the resulting work is displayed in the exhibition, and is believed to be the first made of a dance performance in history.

8. The film industry loves to make reference to his greatest hits

Duncan’s wasn’t the only dedication to Botticelli’s work to be made immortal through film. Terry Gilliam included a great tribute to the artist in his 1988 fantasy drama The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, in which Uma Thurman enters in the image of Venus, cherubs flying down from the lighting fixtures on the wall to swathe her in white muslin. It’s a visually sumptuous affair, beaten only in its artistic licence by Terence Young’s [1962] Bond film Dr. No, based on the Ian Fleming novel, in which Ursula Andress as Honey Ryder emerges from the sea singing dreamily to a conch shell, and clad scantily in a beige bikini. “I promise you I won’t steal your shells,” Sean Connery says as Bond, as he approaches the starlet. “I promise you won’t either,” she responds, clutching a diving knife, in a defiant reworking of the goddess.

9. As does the fashion world – Schiaparelli and Dolce & Gabbana in particular

As Botticelli’s themes and visual references permeated pop culture, so too did they enter fashion’s vernacular – first in Elsa Schiaparelli’s 1938 collection, in the form of ivy wreath necklaces and floral motifs on dresses throughout, inspired by works such as Pallas and the Centaur and the famous Primavera, and later in Dolce & Gabbana’s S/S93 collection, which directly repurposed panels of his greatest works.

10. There is a crater named after him on Mercury

In spite of his enduring connect to Venus, Botticelli’s name has also been attributed to a crater on the surface of planet Mercury. According to the rules of the International Astronomical Union, all craters must be named after an artist who was famous for more than 50 years, and who has been dead for more than three years at the time of naming. No doubt the artist would have been intensely disappointed not to have made it to its neighbour, the second from the sun, instead.

Botticelli Reimagined runs until July 3, 2016 at London's V&A Museum, sponsored by Societe Generale.