The enigmatic model made her way to London from Jamaica in the early 19th century to sit for the Pre-Raphaelites, and her legacy lives on in their impactful work

Who? Lizzie Siddal has long reigned supreme in the minds of historians, artists and writers as the embodiment of the artist’s muse. Her fellow Pre-Raphaelite models, such as Marie Spartali, Jane Morris or Maria Zambaco are less well known, but renewed attention has given many of these women a rightful place in art history beyond the typically limited conception of “the muse”. If you haven’t heard of Fanny Eaton, however, there would be meagre cause for surprise, though surprise there should be: little exists in the way of information about her, and until recent years all that remained was the series of paintings and drawings she sat for.

Fanny Eaton was a black Victorian Londoner and, for some time, painter’s model. Born in Jamaica in 1835, Eaton was the daughter of an ex-slave and, it is suspected, a white slave owner. She came to London in the 1840s and began modelling in her twenties. It has been discovered that she was working as a regular portrait model at the Royal Academy, which is potentially where she caught the attention of the many renowned painters of the era she sat for.

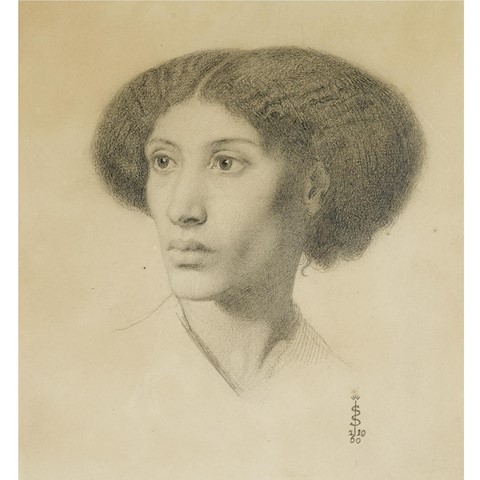

What? That Fanny Eaton made an impact on the artists she modelled for is evident enough from the body of work she features in. In a short period, Eaton sat for John Millais, Joanna Boyce, Simeon and Rebecca Solomon, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Frederick Sandys (with more continuing to be identified). In 1865 Rossetti praises her beauty in a letter to another artist, Ford Madox Brown; this was not insignificant in an era of famously rigid beauty standards invariably heightened by intense racial prejudices. A model of colour would have often been limited by the subject matter in which they could be portrayed, and in some images of Eaton this is palpable. In Rossetti’s famous painting The Beloved we see her peeping from the top right of the scene, almost entirely cut off by the other figures; in another by Millais she is all the way to the far right of the painting, altogether sidelined as a decorative feature. In others, however, we are presented with altogether more refreshing images of a black Victorian woman. There is the regal profile by Boyce which is at once sedate and grand without any touch of heavy-handed exoticism, and then there are the newly identified drawings of her by Sandys, one a tender study for Morgan le Fay and the other an equally delicate rendering in which he has depicted her with faintly rose-tinted lips and a finely wrought nimbus of afro hair.

Her career as a model lasted for around ten years. Much later a census finds her working as a domestic cook on the Isle of Wight at the age of 63, and another shows her back in London at the age 88, where she is known to have died.

Why? Were it not for a surge of attention over the last few years, Eaton could well have been blanched from history, a nameless face and figure in a proliferation of works. She serves as a haunting reminder of the many lives of marginalised people whose existences have been erased. New information and works continue to appear, but much about Fanny Eaton remains in obscurity, and pending more definitive research she may carry on inhabiting the fringes of history. The handful of women who modelled for the Pre-Raphaelites have shaped our contemporary notion of the artist’s muse, and it is vital that Eaton, who cuts such a distinctive figure through her epoch, is incorporated into this narrative.