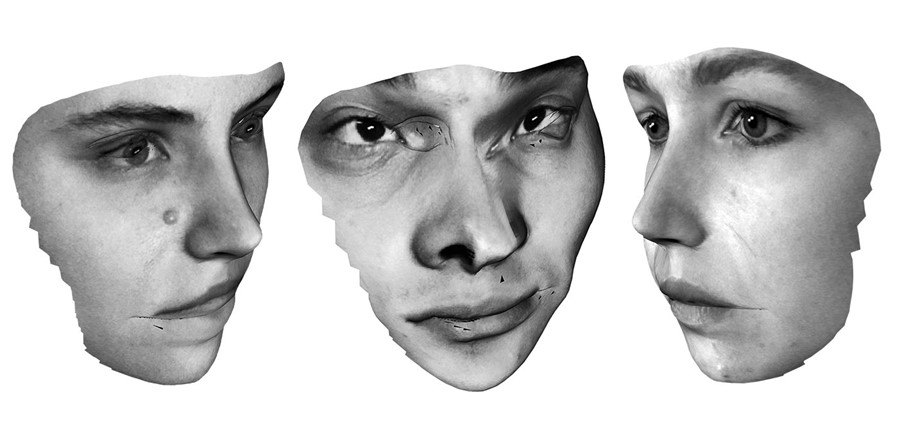

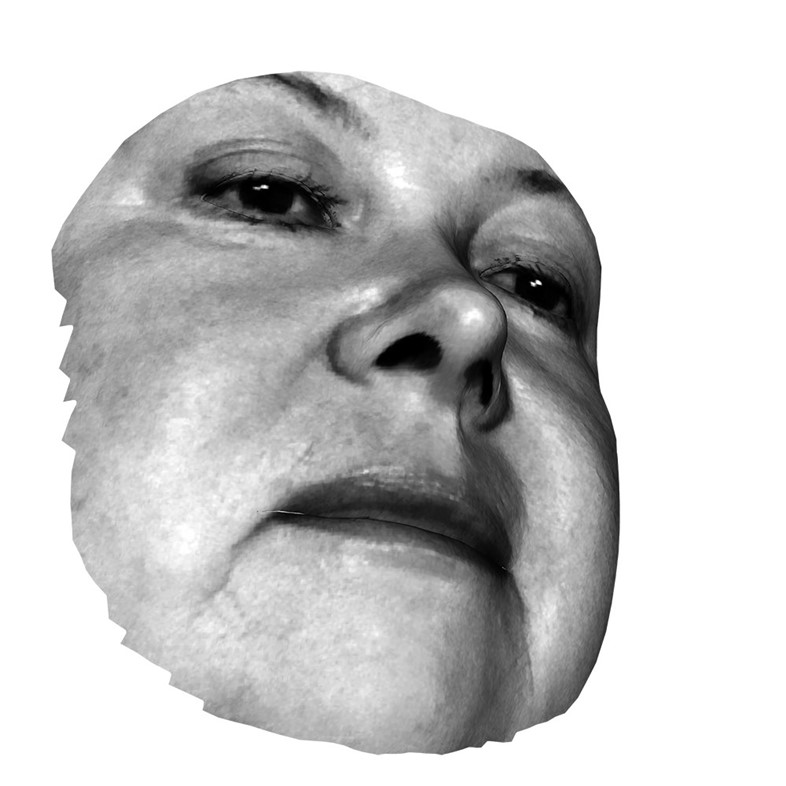

Broomberg and Chanarin's latest series repurposes equipment used to document citizens in modern-day Moscow, resulting in eery images the artists deem "the digital equivalent of a death mask"

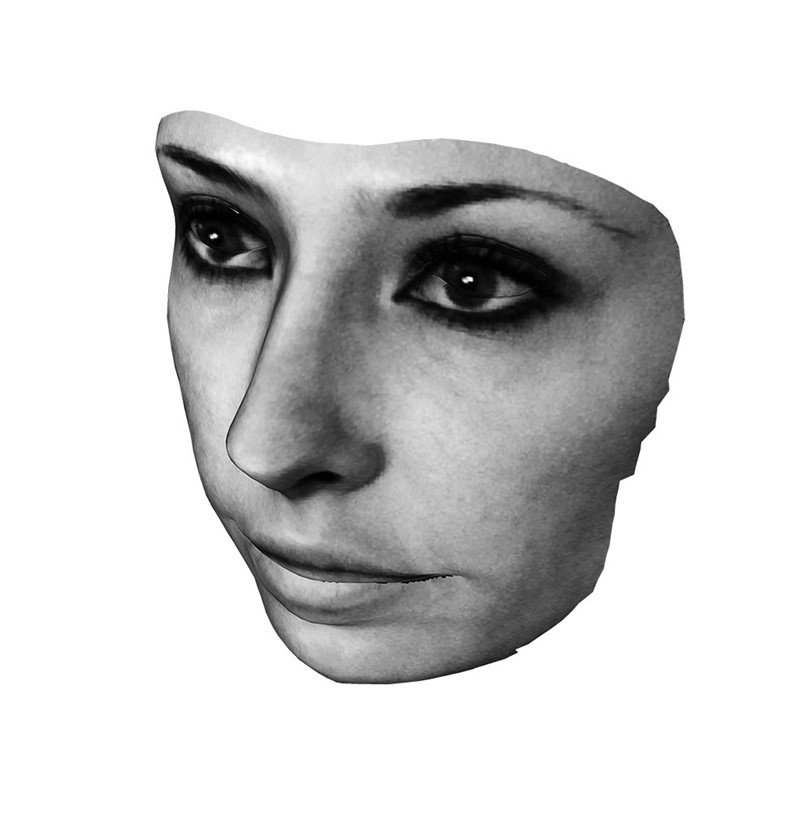

A strangely hollow greyscale face gazes out eerily from the cover of Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s most recent book, Spirit Is a Bone, occupying the liminal space somewhere between an X-ray and a photograph. Its anonymity is very deliberate – the image was created not with a normal camera, but with repurposed surveillance technology usually employed by the Russian government, where it compiles images from thousands of snapshots taken on street corners and in train stations 24/7 – a concept that the artists are very much ill-at-ease with. “This technology is accumulating hundreds of thousands of archival images every day,” Chanarin tells me over the phone. “There is an overwhelming flood of archival and historical information being recorded by the state. That’s a very frightening thought.”

Structurally, Spirit is a Bone is based on German photographer August Sander’s 1926 taxonomy of German society, People of the 20th Century, in which he attempted to create an exhaustive cross-section of what people in 1920s Germany were like by dividing them up into sections – ‘The Farmer’, ‘The Artists’, ‘The City’, etc. Likewise, Broomberg and Chanarin street-cast a selection of people on the streets of Moscow to fill the same categories, but with intriguing new subjects. “For example, we photographed Yekaterina Samutsevich, one of the imprisoned members of Pussy Riot, to replace Sanders’ ‘Revolutionary’,” Chanarin says. “Our ‘Poet’ was the conceptual writer Lev Rubinstein, who composed many of his famous ‘note card poems’ whilst working in the Lenin Library in Moscow.”

The shooting process was an uncomfortable one for Chanarin, largely due to the intensely impersonal way in which the photographs were made: the equipment was set up in a Moscow studio and subjects invited to walk through it while the cameras recorded their image, to create the ghostly, death-mask-like imprint. Partly as a result of the impersonality of this process, the overall impact of the book is unnerving above all else. Still, it is effective in its aim. “We're living in an age when the notion of privacy is being redefined in favour of power," Chanarin says. “What we want to do with this book is to invite people to think about what it feels like to be watched.” In the below quotations from their conversation with architect Eyal Weizman, Broomberg and Chanarin discuss the historical and cultural implications of the work, and question the resonance of the photographic portrait in contemporary society.

On the technology they used to create the portraits…

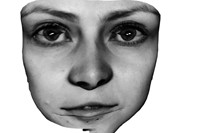

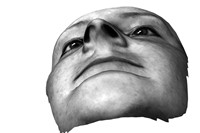

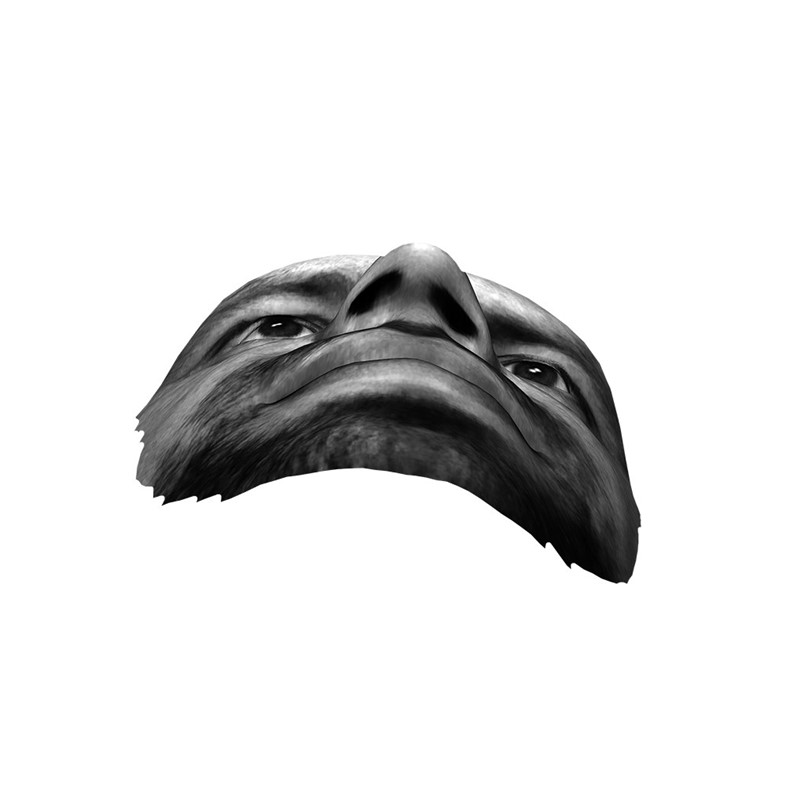

“The portraits in this book were produced by advanced facial recognition technology that is being brought into use, as we speak, in cities around the world. Software engineers in Moscow developed the technology from an existing system built to recognise car number plates. What first sparked our interest when speaking with these engineers was the technical challenge they faced in producing what they call ‘non-collaborative portraits’ – where the subject is neither consensual nor necessarily aware of the camera. These portraits, essentially three-dimensional data maps rather than photographs per se, form a digital archive that can be rotated in space on a computer screen. There is never a moment in the capturing of the ‘image’ when human contact is registered; the subject’s gaze, or any connection between photographer and sitter that we would ordinarily rely on in looking at a portrait, is a complete fiction in this space. What we’re seeing is the negation of that humanity: the digital equivalent of a death mask.”

On the influence of August Sander on the project…

“Thinking about the human face, of portraiture and the defunct histories of physiognomy and phrenology, it’s impossible not to also think about August Sander, who set out to document the society around him during Weimar Germany, after the end of the First World War. He starts with the wholesome person who works on the land, he then moves on to employed people – the Banker, the Baker – and then he progressively moves on to the Poet, the Artist, the Artist’s Wife, and then to more marginalised people: the Unemployed, the Vagrant, the Revolutionary, and ends with ‘The Last People’, comprised of a single portfolio documenting ‘Idiots, the Sick, the Insane and Matter.’

The last of these categories, ‘Matter’, is possibly the most illuminating for our purposes – these were photographs of the dead, one male, one female, followed by a single final photograph, ‘Death Mask of Erich Sander, 1944’, Sander’s son. This image is stripped of any background context, the mask floats in empty space, eerily reminiscent of the portraits in this book."

On the relevance of creating a series about surveillance in present-day Russia…

“Sander was determined to show a full and complete record of Weimar society but unfortunately his project was interrupted by the Second World War and the rise of Nazism. There’s a moral tale embedded in his project that even Sander could not have foreseen. Incomplete at the time of his death, his archive has been subjected to a constant re-reading and re-presenting. On the one hand it’s a heroic attempt to capture and preserve an image of a society reeling from one destruction and on the brink of another; on the other hand his portraits take on a new and sinister meaning when seen through the prism of Aryan supremacy, itself built on the foundations of colonial rhetoric of superior and sub-human hierarchies.

We see disturbing parallels of this totalitarian regime in present-day Russia: from the threat of imprisonment where individuals to all intents and purposes disappear from society to the illegal annexation of whole countries, and the kind of assassination plots so brazen and sensational that you would think they could only exist on a film screen. And all with relative impunity.”

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin's Spirit is a Bone is out now, published by MACK.