Muse, model and lifelong love to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the sole sister in the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood's tragic tale is one worthy of remembrance

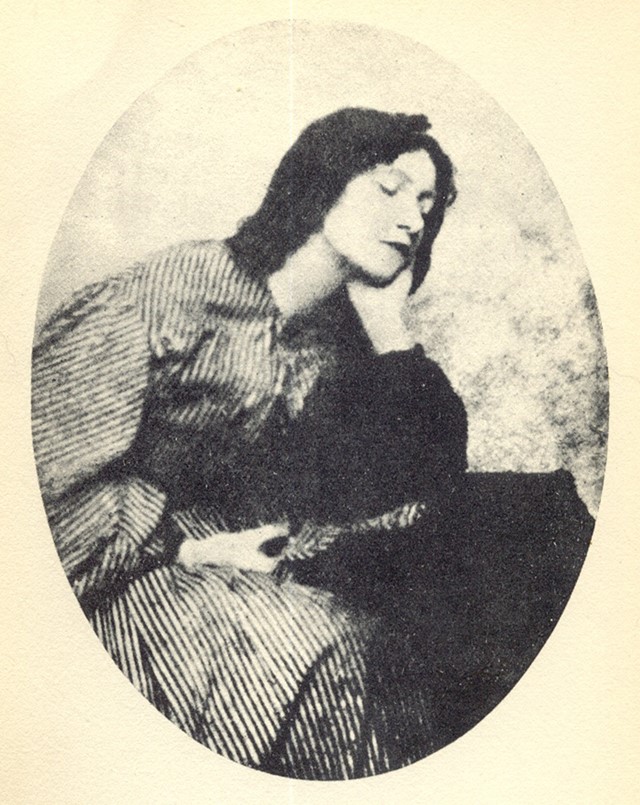

A thick rope of claret red hair, milky white skin and piercing blue-green eyes; Elizabeth Siddal’s recognisable features have become a trademark of the pre-Raphaelite era, in which the classical stylings of artists Raphael and Michelangelo were once again brought to the forefront of contemporary thinking. Above and beyond her physical appearance, however, Siddal’s legacy lives on thorugh her artwork, poetry, and the tragic but powerful story of her life.

Defining Features

Though she came to be remembered for her beauty, Siddal was initially spotted by artist Water Howell Devreell on account of her indiscriminate appearance, as artist’s models often are. “She’s like a queen, magnificently tall, with a lovely figure, a stately neck, and a face of the most delicate and finished modelling,” Howell Deverell wrote after discovering her. “The flow of surface from the temples over the cheek is exactly like the carving of a Phidean goddess.” Indeed, she was especially astounding to artists for her resemblance to the classical goddesses who appeared in the works they so revered – her alabaster skin, vermilion red hair and long neck setting her apart from her contemporaries. By her brother-in-law William Michael Rossetti’s account, her self-regard equalled her appearance. “A most beautiful creature with an air between dignity and sweetness with something that exceeded modest self-respect and partook of disdainful reserve,” he added. “Tall, finely formed with a lofty neck and regular yet somewhat uncommon features, greenish-blue unsparkling eyes, large perfect eyelids, brilliant complexion and a lavish heavy wealth of coppery golden hair."

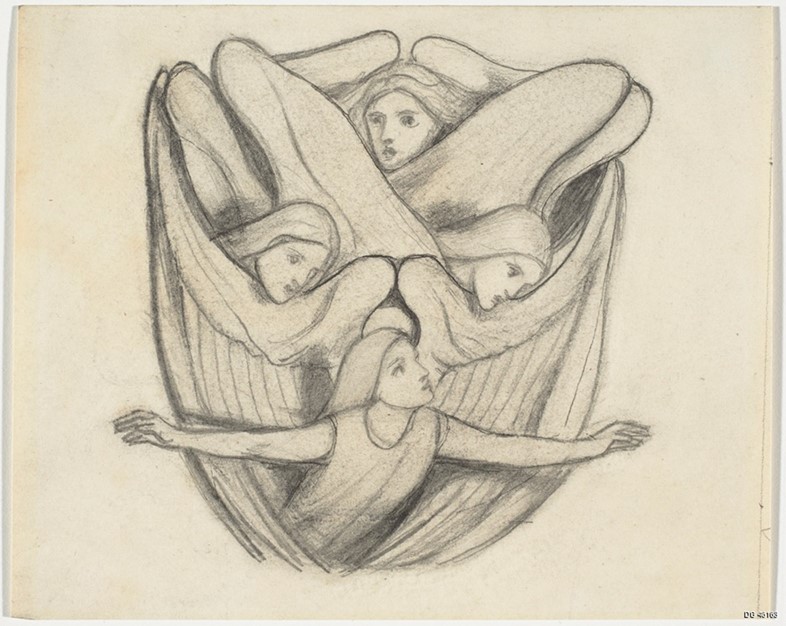

But Siddal’s gifts extended beyond her appearance; she was a talented poet and artist in her own right, creating an archive of work which continues to be shown today. She pursued her creative ambitions in spite of the societal restrictions on the women of her time, and perhaps most markedly, it is partly due to her influence that the name initially attributed to the era – the pre-Raphaelite ‘brotherhood’ – was dismissed in favour of a more inclusive title.

Seminal Moments

Tragically, Siddal’s own life seemed to follow the same trajectory as one of the characters in a classical tragedy she so readily played. She was plagued with bad health throughout her life, taking trips to France and Italy in an attempt to cure it – one particularly famous bout striking her after sitting for John Everett Millais’ now famous painting Ophelia. In the winter of 1852 the artist began working on the epic work, with Siddal posing in a bath full of water as his tragic subject – but the hours in the cold gave her pneumonia so extreme that she almost died.

Her enduring love, particularly that for artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti, was similarly troublesome. She met the artist not long after her discovery by Deverell in 1849 and soon fell deeply in love with him, but their difference in class – Siddal being born into a working class family and Rossetti an upper class one – prevented them from marrying immediately. Nonetheless, within two years he had dismissed all other models in preference for her, and she, expressing her interesting making her own artwork, began to study with him. They became engaged several times, but Rossetti broke it off repeatedly – and perhaps as a result her poor health was accompanied by stretches of severe depression, which she self-medicated with laudanum. “I sit in thy shadow but not alone,” she once wrote, in a haunting but affectionate allusion to the artist – and likewise, her goddess-like image to her lover became a heavy burden on Siddal herself.

By the time Siddal and Rossetti finally married, in 1860, she was so frail that she had to be carried to the church. She miscarried her first child one year later and, heartbroken and defeated, took a deadly overdose of laudanum not long afterwards. Even in death, however, Siddal’s legacy continued. So destroyed was Rossetti by his grief for the flame-haired beauty that he buried his only manuscript of a series of poems he had written about her in her coffin. Seven years later, plagued by the belief that the manuscript was the best work of his life, and lost forever, he had the coffin exhumed to retrieve the poems. As the legend goes, he found Siddal as beautiful then as she had been alive – rumours that her hair had continued to grow, and by now filled the coffin, delight fans of her story.

She’s AnOther Woman Because...

If Siddal was first propelled to fame through her aesthetic appeal to the pre-Raphaelites, then her legacy is preserved by her merit. Over the course of her short life she created a collection of artwork which continues to be shown today, most recently in exhibition Pre-Raphaelites on Paper: Victorian Drawings from the Lanigan Collection, currently on display at London’s Leighton House, while her likeness continues to gaze out longingly from such masterpieces as Millais’ Ophelia, and Rossetti’s musings on Botticelli’s Venus.