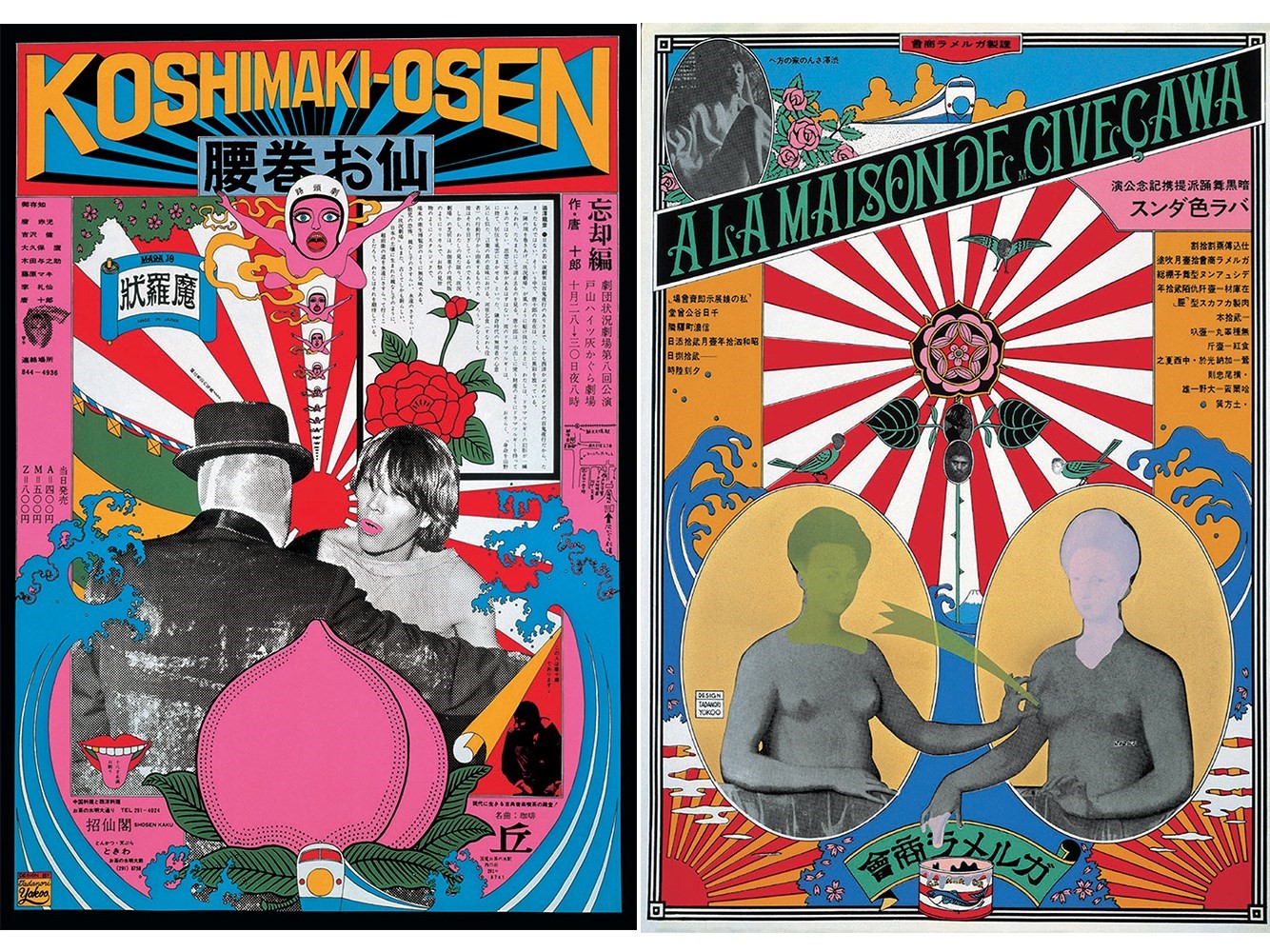

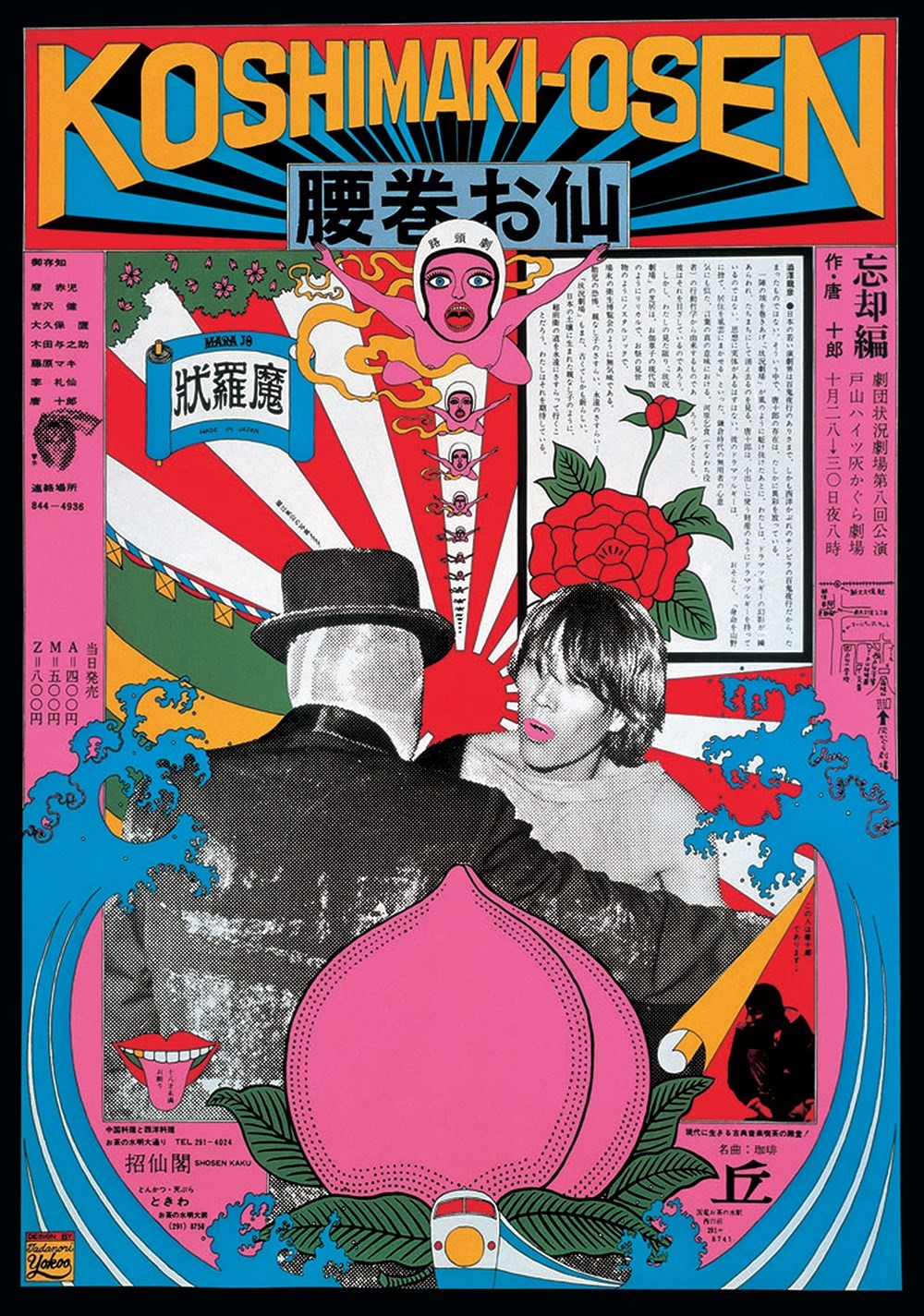

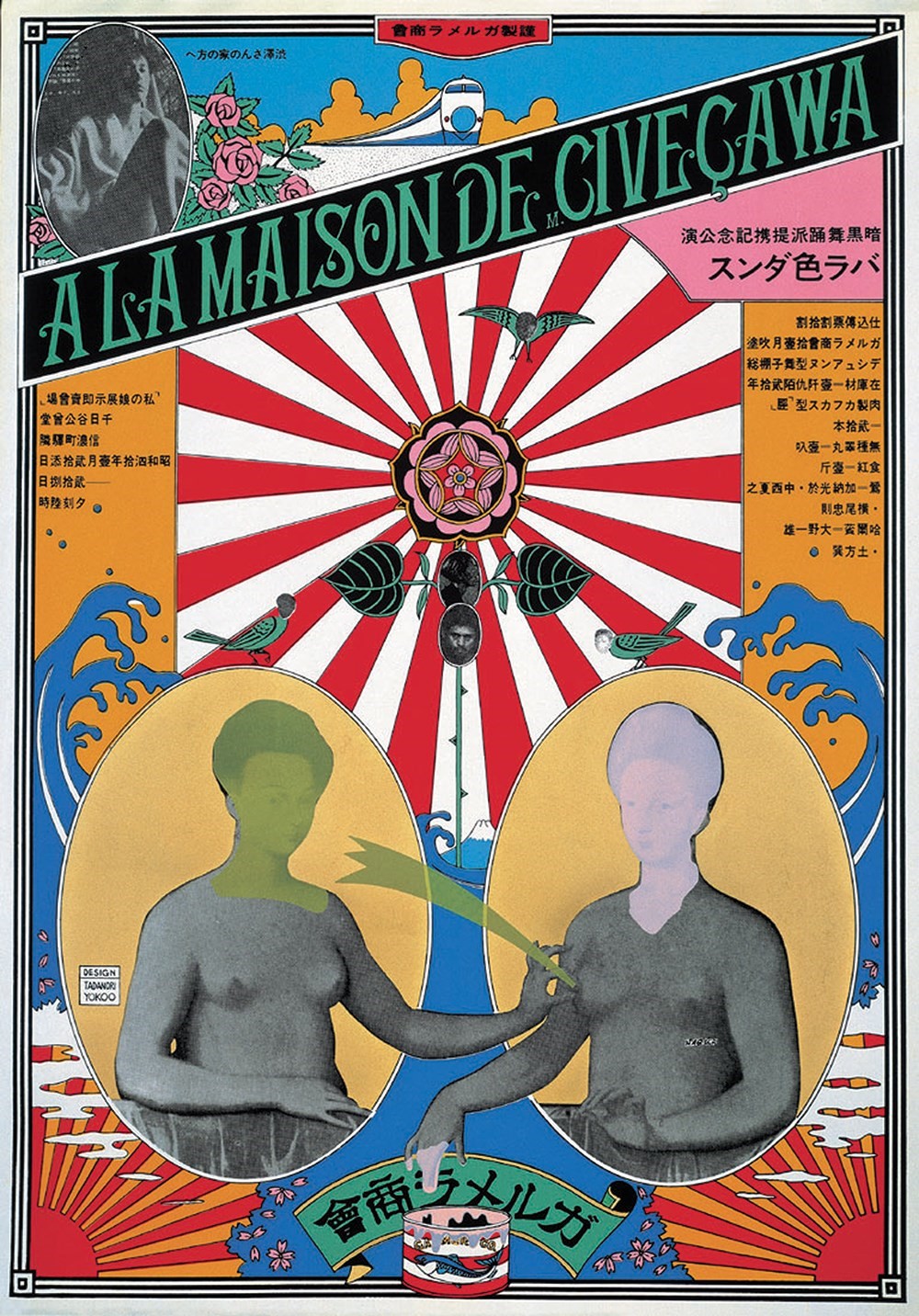

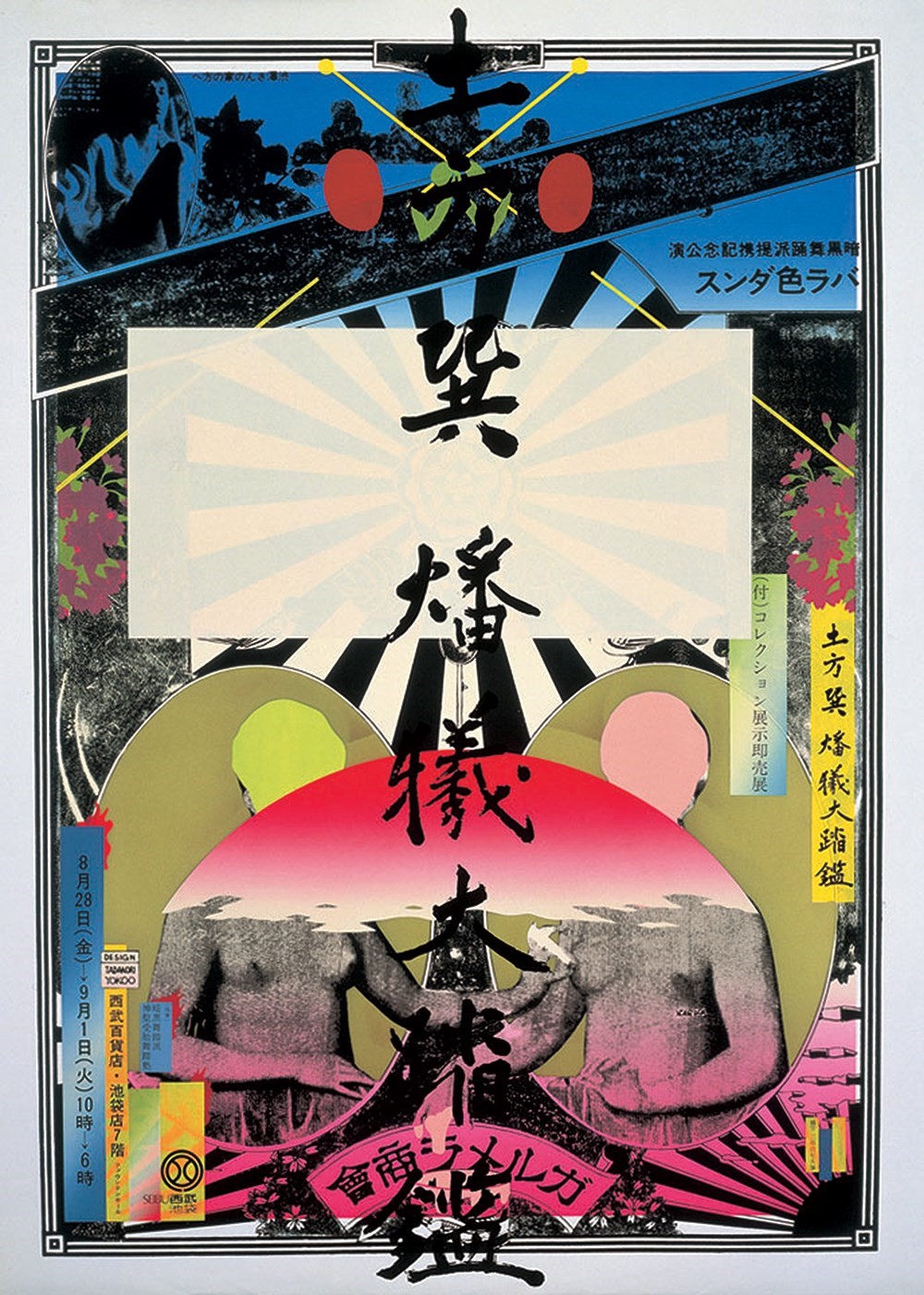

A talented 24-year-old graphic designer with dreams of becoming a painter, Tadanori Yokoo arrived in Tokyo in 1960, just as the city was erupting into civil disobedience. His timing was perfect: something was in the air; Japan’s youth were feeling disruptive and so was Yokoo. Mixing Andy Warhol’s pop and Peter Max’s psychedelia with traditional Japanese woodblock prints, known as ukiyo-e, his commercial work – mainly posters for theatre productions and movie releases – became crazed visual poems, pieces of pure creative expression that had little to do with the subject matter. His subversive, autobiographical and playful style (a 1967 poster for the play John Silver features an apology to the director for finishing the artwork late) immediately chimed with Tokyo’s growing counterculture, and Yokoo soon found himself at the epicentre of all things avant-garde, collaborating with scandalous writer Yukio Mishima, theatre radical Shuji Terayama and even starring in Nagisa Oshima’s agitprop film Diary of a Shinjuku Thief.

Following a trip to New York in 1967, where Yokoo was introduced to Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, the West woke up to Yokoo’s inimitable aesthetic. From The Beatles and Earth, Wind & Fire to Santana and Emerson, Lake & Palmer, he became the go-to artist for far-out rock bands; he lent his dreamy visuals to a poster for Roger Corman’s acid B-movie The Trip; and, in 1972, he was honoured with a solo show at MoMA. Today, with a museum of contemporary art in Kobe named after him, the 79-year old indulges in his childhood fantasy of painting canvases.

When did you realise that imagemaking was your future?

During my last year at high school I won first prize for a poster design for a textile festival, which was then printed and put on display to the public. I decided to take advantage of the opportunity and two years later I became a graphic designer… but, really, I always wanted to be a painter.

Arriving in Tokyo in 1960, what was the atmosphere like?

The situation in Tokyo was totally political. There was a big campaign against the Japan–US Security Treaty, and the city was full of radical student movements. But there was no real cultural movement among young people back then.

Were you involved in any protests? Did you connect with that sense of unrest?

I only got involved once: it was in the mayhem in front of the Parliament house. Looking back, designers were ultimately on the side of the establishment but, personally, I was against it.

How did American culture begin to influence your work?

After a while, the political climate in Tokyo began to slowly calm down. By 1967, underground movements were beginning to emerge and, as a result, my inner Modernist totally disappeared. In its place I started fusing my innate Japanese aesthetic with American Pop Art, which produced all my major 60s work.

You’ve collaborated with so many amazing people – from the writer Yukio Mishima and fashion designer Issey Miyake to theatre director Shuji Terayama… How did these projects come about?

I’ve never personally asked to do a collaboration. Almost all of them were the result of requests by other people. I’ve always been a kind of passive person: my motivation has always come from others. But through these projects, the consciousness of my collaborators would activate my inner self.

Describe your first experience of New York in 1967…

Back then, of course, people couldn’t instantly share their experiences with everyone around the world, like it’s possible to do today. So all the movements that were happening in New York were totally unknown to me. But, in the midst of the hippie revolution, I suddenly discovered Indian and Japanese Zen.

In later years you’ve focused more on painting… Do you have a different mindset between painting and design work?

For me, design is a job and painting is a life. Painting is something you can struggle against with your entire body and soul, and I believe your life and creating should be totally free. Your mind changes everyday, so painting should ceaselessly change. Your body will become old but your artistic creativity should never age. Like your body, painting should never stop changing. Change is creation. So creation is always unfinished.

Do you have an unrealised ambition?

At the moment I’m trying – in my own way – to create a picture that interprets and then deconstructs Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp changed the very idea of art. But I have no particular ambition; I think it can mislead you and you can lose yourself in it. I believe a painting should be created naturally, and has nothing to do with your ambition.

This story appears in the S/S16 issue of Another Man.

Tadanori Yokoo is represented by Albertz Benda gallery, New York. His exhibition 49 Years Later ran between November 12 and December 19, 2015.