The oeuvre of Colin Jones – a ballet dancer turned prolific photojournalist – paints a powerful and honest reflection of post-war Britain, and is well worth revisiting in a new London exhibition

Who? The story of Colin Jones’ life, which has seen him go from evacuee, to ballet dancer, to photographer and then to treasured and prolific photojournalist, has more than a hint of Billy Elliot about it. He was born into a working class household in the East End of London in 1936, and was only a few years old when the Second World War saw him evacuated repeatedly to the countryside to escape the ravages of the bombings. The upheaval deprived a young Jones of an education – but fortunately for him, he was talent-spotted early on, and quickly picked up by the Royal Ballet.

"They trained him from a very young age, and he became part of their touring company," Clemmie Cooke, the director of the Michael Hoppen Gallery, explains, on the occasion of the institution’s new exhibition of his work. It was later, while touring in South Africa, that he first started taking photographs. "It was essentially around the time of the Sharpeville massacre – and of course there were always a lot of photographers around photographing the stage when he was dancing. He became aware of the power of photography, and he started buying his own cameras." It wasn’t until he returned to England, however, that Jones happened upon his first great subject: the mining life. "He was on a trip, I think, from Newcastle to Sunderland, and out of the window he saw all of the mining heaps. He ran away from his ballet class and went and photographed them, and developed them when he got back to his grotty hotel. And essentially from then on in he became obsessed with that."

Before long, Jones had been picked up by The Observer, and began working on the series which was to become Grafters – the world of ballet eventually giving way to that of photography. "The parallel between the life of a dancer and the life of a miner was something he was quite interested in," she continues, both being "incredibly physically challenging, and having very short shelf life." From Grafters, Jones went on to become an incredibly accomplished photojournalist, developing a sprawling body of work which would give representation to those he shot.

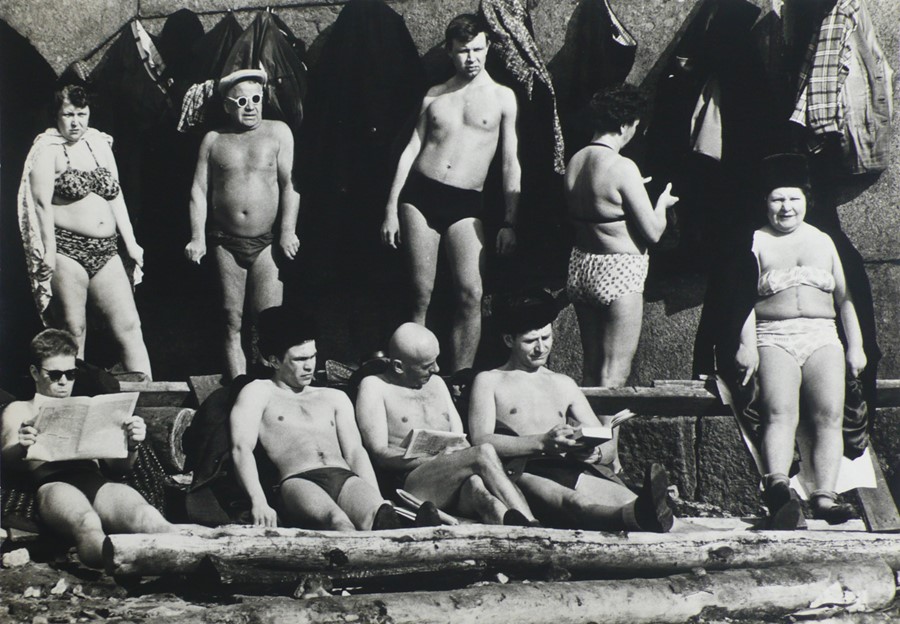

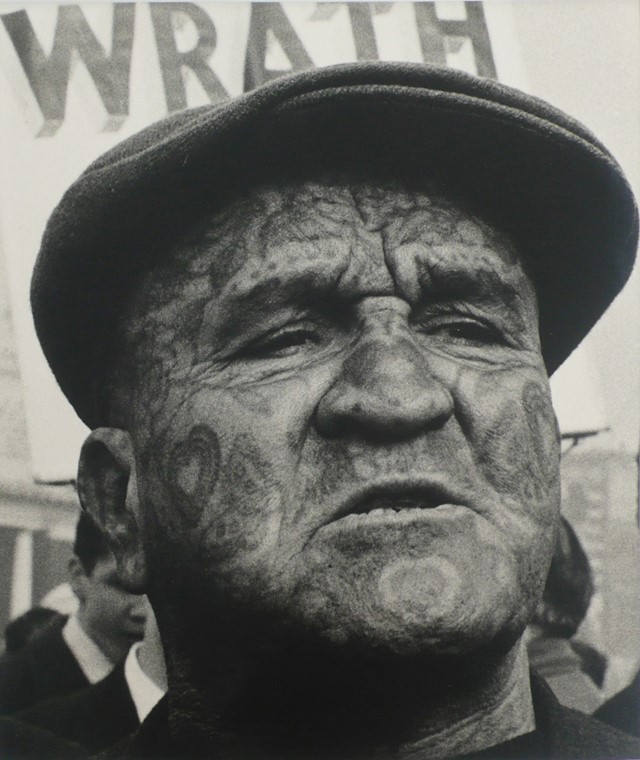

What? Jones was a keen documentarian of life as he discovered it around him, in the cracks and crevices of the mid-20th century, and with the benefit of hindsight, his archive now serves as an invaluable historical resource. "He has documented a lot of Britain that no longer exists," Cooke continues. "It is a eulogy to a way of life that has a past. For example, if you look at the herring fisherman's wives, they are wearing these extraordinary little white bonnet caps – I think the date on it is ’68 – to keep the herring oil out of their hair. So I think there is also this sense that he has captured, and sort of plotted for us in time, these moments and these ways of life that no longer exist."

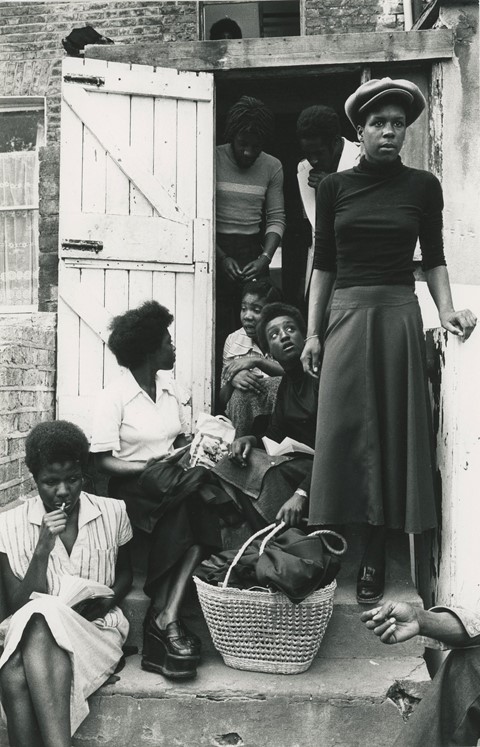

Jones' technical skill is a thing to be admired – his crisp, clear shots and niftily constructed compositions give a transparency to all manner of difficult subjects – but it is the warmth and rapport with which Jones approaches his subjects which most resonates throughout his oeuvre. Each shot seems to have been watermarked with a striking and unmissable empathy. "He has a really non-judgemental eye, and I think that is relatively rare within documentary photography," Cooke explains. This comes into its own in his series The Black House, made between 1973 and ’76. Harambee, as it was officially called before it became derisively referred to as the Black House, was a community project intended to house vulnerable black youths, many of them second-generation Caribbean migrants, who were discriminated against by local authorities, and who, as a result, struggled to stay in school or to hold down a job.

Harambee, set up by a dynamic Caribbean migrant, offered an alternative – and Jones spent months building up the trust of those who lived in the house in North London's Holloway in order that he might photograph them. "He did it initially as a Sunday Times commission, but of course it grew on from that, and he became very good friends with them," says Cooke. "He used to be used as a reference when they went to jail, and things like that. Though entirely different in subject matter to when he was photographing the Liverpool docks, and the demise of industrialism in this country, it is the same eye – it is that very empathetic, very quiet, unjudging eye. And I think his subjects really could tell. There is a comfort in the way people let him take their photographs."

Why? Now, as Colin celebrates his 80th birthday, the Michael Hoppen Gallery in London is serving a second exhibition of his startlingly extensive body of work – the first being the show which opened the gallery 24 years ago. The eponymously titled retrospective is an exhubrant celebration of his life and experiences – though selecting the works to be included in the display, this time as before, was no mean feat. "Colin is pretty prolific, and there is an incredibly large body of work, so what we have tried to do is show all the different areas of his work within the context of the exhibition – and a lot of the slightly lesser known works as well," Cooke says. What's more, the time lapsed between the two shows places a new emphasis on the timelessness of the work on show, while the change in context shifts its meaning.

The key takeaway from this newest exhibition of his work? Jones' astounding contribution to the documentation of British culture. "The 20th century is littered with fabulous documentarian photographers, but in Britain we don't have nearly as many as, say, North America, where they are much more into documenting their traditions, or Paris even, where there is much more," Cooke says. "I feel like our own small island hasn't been as well documented. Colin definitely did that."

Colin Jones, Retrospective runs until June 3, 2016 at Michael Hoppen Gallery.