Art historian Noam Elcott shuns humanity's pursuit of light in favour of an alternative cultural history, viewed through invisibility suits and Bauhaus performance art

According to cultural historians, human fascination with light – especially artificial light – has transformed modern life. From urban environments and the theatre, to technological media and the cinema, not to mention the growing domain of light as an artistic medium in its own right, it pervades everything we touch. Now, however, a new book called Artificial Darkness by art historian Noam Elcott comes at light from the other end of the spectrum. Brilliantly researched and stunningly argued, it reveals ‘artificial darkness’ to be a historically specific phenomenon – an ‘arrangement’, to be more precise – which gave birth to a surprising array of spectacular visual experiences, effects and imagery.

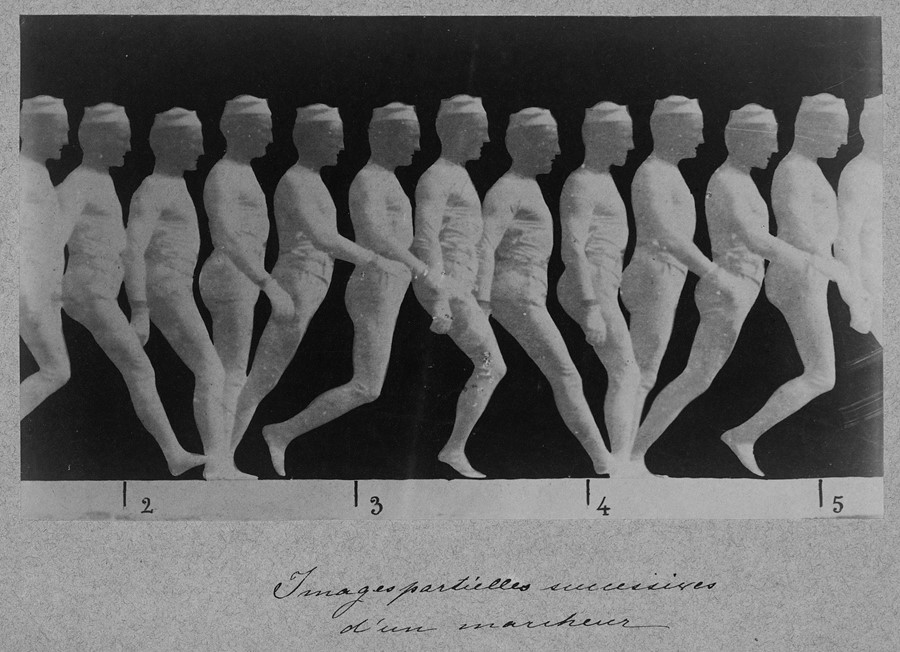

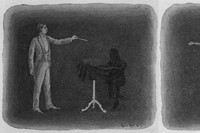

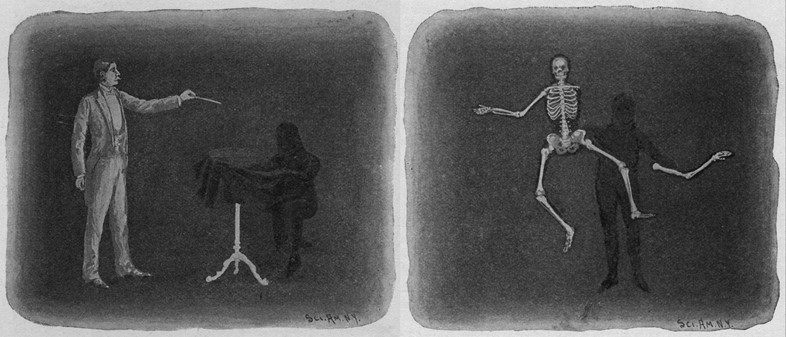

Think pitch-black theatre auditoriums in which light is made highly dramatic (the blueprint for later cinemas); Étienne-Jules Marey’s pro-cinematic experiments registering moving bodies against black backgrounds; Black Art magic; Georges Méliès’s trick films. Clearly, artificial darkness was very often light’s ‘hidden’ companion, and was almost as vital in the shaping of modern visual phenomena. Only, until now, it has been all too easily overlooked.

Elcott’s book zeroes in on the notion of darkness as a ‘controlled condition’, showing how it was harnessed across a range of different image-making contexts. A slippery phenomenon, darkness tends to succeed in its purpose of making itself obscure. Thus, the book reconstructs its use in great part from the spaces and texts surrounding that which was made visible: “Darkness only becomes perceptible,” Elcott notes, “when we track it across scientific treatises and laboratories, operating manuals for photographic studios and cinema owners, surrealist and Hollywood film, avant-garde dance, paintings, and books, and hosts of other venues.”

The book does just that, cutting across these diverse creative fields with the same elegance and erudition with which it takes on a whole range of academic disciplines. Here, AnOther sits down with Elcott to discuss his motivations for writing the book, his thoughts on darkness in the age of Enlightenment and, last but not least, that quintessential black body suit.

On arriving at the subject of darkness...

“Like many others, I began writing the history of art and artificial light: photography (the writing of light), illuminated architecture, and so on. I soon realised that the history of artificial light could not be told without the history of controlled darkness. But only after years of research and thought did it occur to me that the story could be told differently – and more compellingly – from the perspective of darkness: the invention and patenting of photographic darkrooms; the darkening of theatres and cinemas; the construction of ‘black screens’ for scientific imaging, trick cinematography, avant-garde dance and other attractions.”

On why darkness has remained ‘invisible’ to the media, theatre and art historians...

“Darkness obscures; it cloaks everything it touches. Artificial darkness not only obscures object and bodies, but also itself; it cloaks the cloak. For example, when we are forced to grope in the dark, we become hyperaware of our immediate environment. But when we are in the cinema (a prime site of controlled darkness), we focus on the luminous image and forget entirely about our surroundings. In the words of the Surrealist poet and cinephile Robert Desnos: ‘the hall and spectators disappear’. Artificial darkness enables other types of vision, and so renders itself invisible. We can describe artificial darkness as a technology of invisibility. Artificial darkness is the invisible technology behind Hollywood blockbusters like The Invisible Man (1933). The black suit and traveling matte shots not only rendered [English actor] Claude Rains invisible, but also made themselves imperceptible to the viewer.”

On traditional versus modern connotations of darkness…

“The fundamental difference between ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ darkness is that the latter is controlled and deployed like other technologies. Traditionally, darkness is aligned with ancient or primordial chaos that is overcome through artificial light and Enlightenment. The name is more than a pun; it betrays the philosophical orientation of the West, if not the whole world. Artificial darkness – like artificial light – is a product of modernity, not its antithesis. Artificial darkness advances the rationalised, technologised project of modernity – but with different means. Modernity did not negate darkness so much as bend it to its will.”

On the persistence of narratives of terror and macabre in artificial darkness...

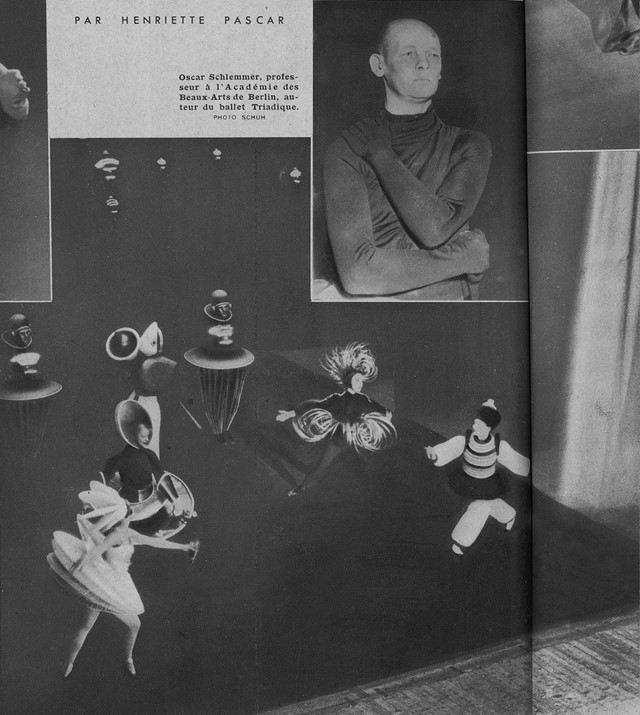

“There is no question that the historical connections between darkness and the macabre were not entirely severed with the rise of artificial darkness. [1933 science fiction horror film] The Invisible Man with Claude Rains, for example, is certainly a Gothic tale. But black screens were also used to insert the angel Gabriel into the annunciation scene in Ferdinand Zecca’s 1907 film The Life and Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ, or to facilitate the abstract dances choreographed at the Bauhaus by Oskar Schlemmer. Just as artificial light was an essential ingredient of film noir, so too artificial darkness traversed a wide range of cultural domains.”

On camouflage, and the surprising star of the book…

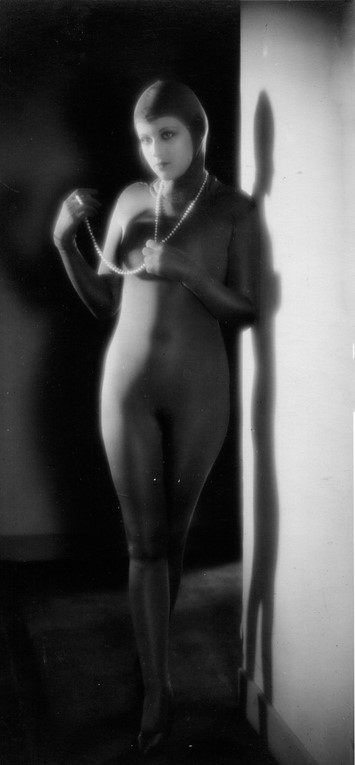

“The invisible star of the book is the black body suit. Scientists like Marey (or, more precisely, his assistant Demenÿ), magicians and early filmmakers like Georges Méliès, and avant-garde artists like Oskar Schlemmer all used it in their work. When worn before a black screen, the black body suit allowed its bearer to vanish, entirely or in pieces. To the horror and delight of his audience, Méliès used a black velvet bag to decapitate himself; Schlemmer likewise made legs and arms disappear in favour of abstract shapes like spirals and spheres; the Russian theatre director Konstantin Stanislavsky too envisioned innumerable uses for the black costume on a black set, including the fabrication of thin actors from fat ones, but he only got to realise few.

Today, black suits and screens have yielded to blue-screen and green-screen digital effects, or they’ve found contemporary descendants in the form of various Cat Woman suits, which, like their early 20th century ancestors – such as Mudisora in Feuillade’s serial thriller Les Vampires (1915-16) or Le Perle (1929), a Belgian Surrealist film directed by Henri d’Ursel – are black bodysuits that infuse eros into everything they conceal. And yet, there are still a number of artists who marshal the black costume and black screen toward fantastic, artistic, and erotic ends, like Polish artist Aneta Grzeszykowska. Historically, the black suits facilitated disappearances and horrible acts of self-dismemberment when worn by men but when worn by women, they were pure eros. Grzeszykowska’s work surprisingly and compellingly combines these two strands.”

On researching the invisible…

“Many of the most important practitioners of artificial darkness kept their techniques a closely guarded secret. Méliès did not reveal his tricks until the final years of his life – and then only in an obscure conjuring magazine. Schlemmer never owned up to his debt to variety theatre and magic. And, of course, critics could not write about techniques that remained invisible. What’s more, few philosophers or aestheticians bothered with the technology of darkness. So I was forced to delve into technical literature – all the treatises and manuals – and I had to see techniques of invisibility even when they remained invisible in images or unstated in texts.”

On working across disciplines…

“My primary interest lies in avant-garde art. So I was especially pleased to discover that artificial darkness generally – and the black screen in particular – held the key to the enigmatic abstract dances and ballets choreographed by Schlemmer, the head of the theatre workshop at the Bauhaus, which was perhaps the most important art and design school of the twentieth century. But avant-garde art and dance alone cannot explain the phenomenon of artificial darkness. I gradually realised that it wasn’t so much a question of whether this history could be told across different sites and contexts but, rather, that it had to. Indeed, this is another reason why artificial darkness has largely remained invisible – it exceeds the purview of any one discipline, and requires an interest and knowledge in the history of art, film, science, magic, theatre, architecture...”

On the book’s relevance for today’s image-making technologies and media…

“The uniquely modern forms of darkness enumerated throughout the book are now history. Taken separately and together, darkrooms, cinemas, and black screens figure marginally, if at all, in the production and circulation of contemporary media images and subjects. Modern artificial darkness has yielded to ever more luminous and ubiquitous screens. And yet, new aesthetic and historiographic possibilities emerge. The media guru Marshal McLuhan once observed that as an airplane breaks the sound barrier, sound waves become visible on the wings of the plane. He wrote that ‘The sudden visibility of sound just as sound ends is an apt instance of that great pattern of being that reveals new and opposite forms just as the earlier forms reach their peak performance.’ I think in a similar way, artificial darkness has now become visible only because it is technically obsolete.”

Noam Elcott, Artificial Darkness: An Obscure History of Modern Art and Media is available now, published by Chicago University Press.