As the first major exhibition dedicated to neon is set to open in Blackpool, we chart its luminous ascent from lighting device to modern artistic medium

The word neon immediately conjures up visions of lurid dance scenes in stuffy Soho nightclubs or underground speakeasies. It calls to mind advertising slogans, too – the illuminating clash of colours in New York's Times Square, or more simply, the fluoro Lucozade bottle advert that once livened up the M4 motorway. And thanks to a handful of progressive artists during the 1960s, it also became indelibly linked with modern art.

Next week, Neon: The Charged Line opens at Blackpool’s Grundy Art Gallery. The first major show dedicated to the medium, it spans 50 years of neon art history, demonstrating exactly how much has changed since it was first popularised as an art form in the 60s, having previously been reserved for lighting and signage alone. "In Europe – and France and Italy in particular – artists were exploring everything from geometric abstraction and Op Art, to using text either to respond to architecture, or within the fold of Arte povera," says Grundy Art Gallery curator, Richard Parry of the earliest creative innovations in neon. "In the States you had Joseph Kosuth interested in the philosophy of language, whilst Dan Flavin was using the fluorescent tube (a close sibling of neon) to set up a play of light and space, and Bruce Nauman was utilising it to create visual puns."

Skip forward to the 1990s and you see neon in the hands of YBAs Tracey Emin, Gavin Turk and Cerith Wyn Evans. Neon: The Charged Line represents "key trajectories in art practice", Parry explains, and features a broad spectrum: from the early conceptual work of Kosuth and the geometrical abstracts of François Morellet; to works by female artists Emin and Brigitte Kowanz; to a "critical snapshot" of how neon is currently used by artists, and by those working out of England’s North West. Running alongside Blackpool’s famous Illuminations – the annual light festival, founded in 1879 – the exhibition forms part of LightPool, a £2.4m project to support the centuries-old light display of the northern seaside resort. "There is definitely something enduringly magical about light – we can’t help but be drawn to it," Parry observes. "Perhaps we are all moths at heart." Here, ahead of the show's opening, we chart the integral influence of Emin, Turk and Evans on the medium, alongside an artwork from each set to feature in the exhibit.

Tracey Emin

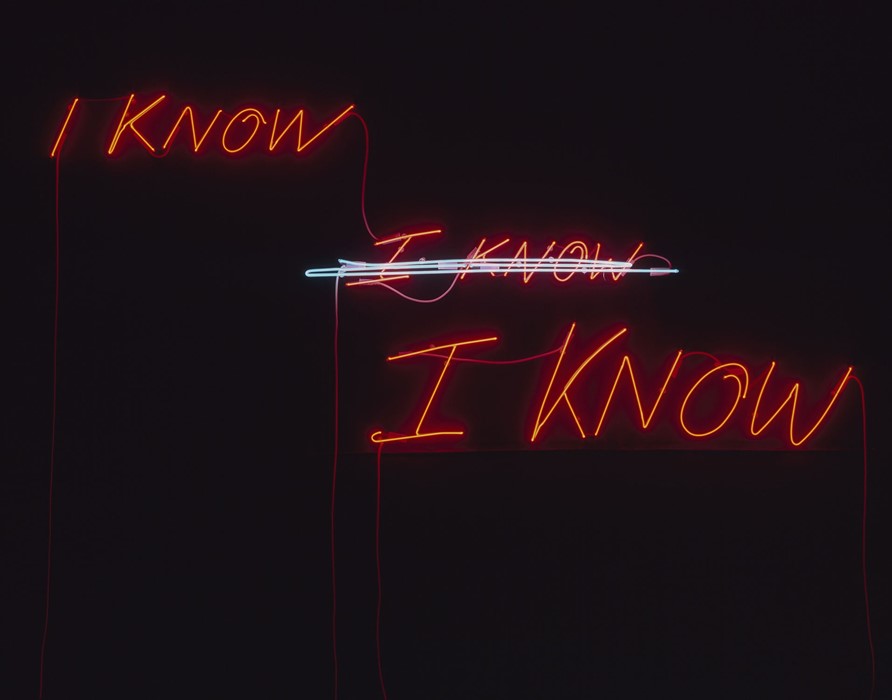

Unmade beds and tents aside, YBA Emin is perhaps best known for her works in neon, having experimented with the medium since the early 90s. Her text pieces, crafted to mimic her own handwriting, convey emotion, experience and thought. Open to interpretation, they range from such affirmations as The Last Great Adventure Is You (2014) – where the 'You' refers not to another but to the self, as if spoken to a mirror – to declarations such as the coral pink scrawl, More Passion (2010) – donated to the Government Art Collection, now hanging in Number 10 Downing Street – and messages of love: My Heart Is With You Always (2014) and The Kiss Was Beautiful (2013). On display at the Grundy Gallery, in red and blue neon, is I Know, I Know, I Know (2002); aggravated repetition with which many can identify.

Gavin Turk

Conceptual artist Gavin Turk rose to fame when he failed his MA at the Royal College of Art. Where for others a final show meant displaying bodies of work, Turk whitewashed his space and erected an English Heritage-style blue plaque at the end of it: "Gavin Turk sculptor worked here 1989-1999," it read. He infuriated college rector, Sir Jocelyn Stevens, but caught the attention of renowned art collector Charles Saatchi. Turk’s waxwork Pop (1993) later featured in Saatchi’s notorious Sensation exhibition (1997).

Turk’s oeuvre largely focuses on questions around authorship, appropriation, influence and identity. Regularly humorous and often referencing such figures as Andy Warhol, Turk’s 3D Trompe-l’oeil sculptures are arguably what put him on the map – think: Bag (2000), a stuffed bin bag cast from bronze and painted black, or Nomad (2002), another painted bronze cast of a figure concealed within a sleeping bag.

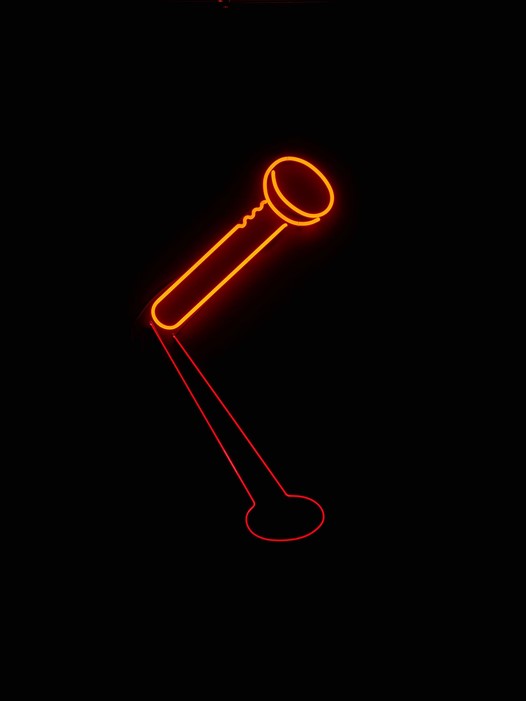

Turk’s neon works typically depict everyday images – a burning match, a lobster, a half-opened door. "Neon works tend to look like you could buy them off a shelf," he told The Spectator in 2014. "Neon is a threshold, it’s the sign above a shop door, commercial yet symbolic." Turk’s One Twenty Five exhibited in Neon: The Charged Line is a red neon nail, positioned so that it, and its shadow, appear as the time 01:25 would on a clock face. Turk’s most famous ‘nail’ is the permanent 12-metre bronze sculpture, Nail, positioned at the entrance of One New Change shopping centre in the City of London.

Cerith Wyn Evans

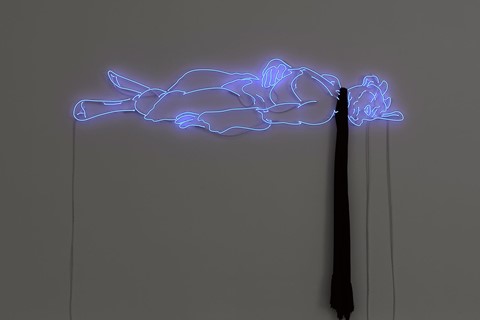

The oeuvre of Welsh conceptual artist Cerith Wyn Evans largely centres on language and communication – of new ways of looking at communicatory practices. Text from film, literature and philosophy, as well as the influence of John Cage, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Marcel Proust and Andy Warhol (to name a few), regularly infiltrate his art. Much of his work is site-dependent too; exhibition spaces are used as springboards enabling his installations to accumulate a number of meanings, leading to varying experiences.

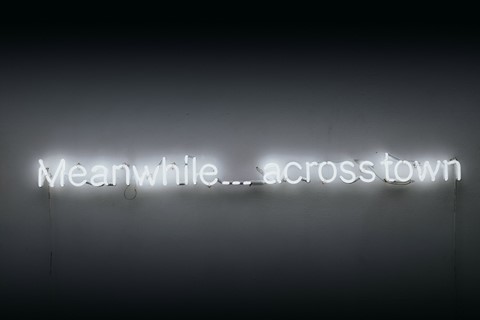

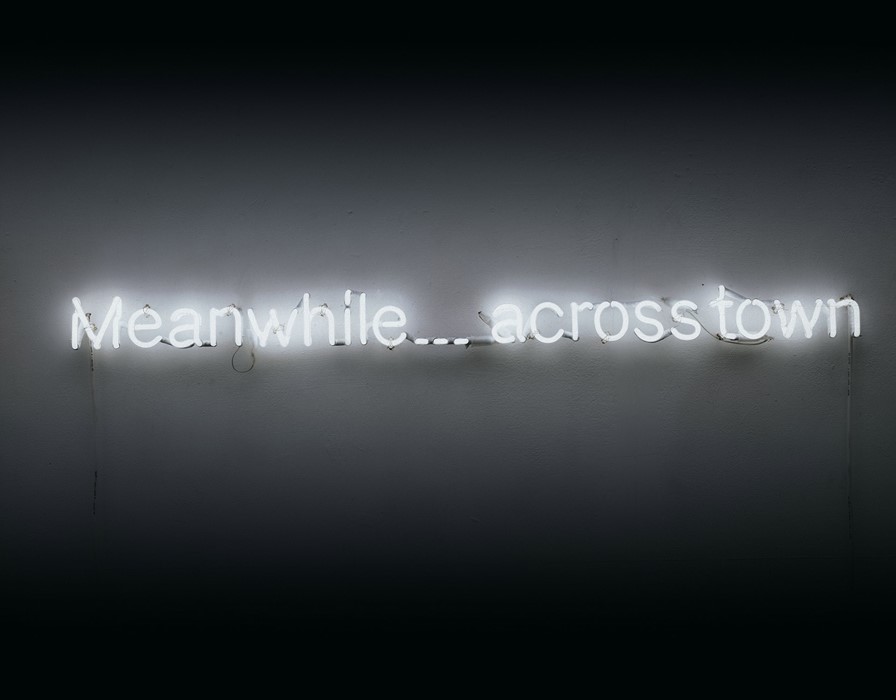

His neon texts and Morse code-transmitting chandeliers are amongst his most critically acclaimed work. Starting out as a filmmaker in the early 70s, it was not until the 90s that he turned his attention to installation and sculpture. He has continued to work with these mediums ever since. Meanwhile… across town (2001) is an installation of white neon text with undeniable associations to film, while TIX3 (1994) – ‘EXIT’ spelled backwards – invites the viewer to consider notions of space. Both these works are to sit amidst eight rooms of others, all contributing to the luminous spectacle that is Neon: The Charged Line.

Neon: The Charged Line is at Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool from September 1, 2016 – January 7, 2017.