One of the successes of the Rencontres d'Arles – the annual festival of photography – in 2014 was an exhibition curated by Christian Lacroix on the subject of l'Arlésienne, the eternal (and unattainable) paragon of the region. It was a strange show, mixing historical and contemporary documents under the baroque ceiling of one of Arles' many chapels, high art and low. The majority of the works shown were by Katerina Jebb: some conventionally presented on the walls, but also almost life-size images of women in the distinctive Arles costume, standing up in the middle of the space.

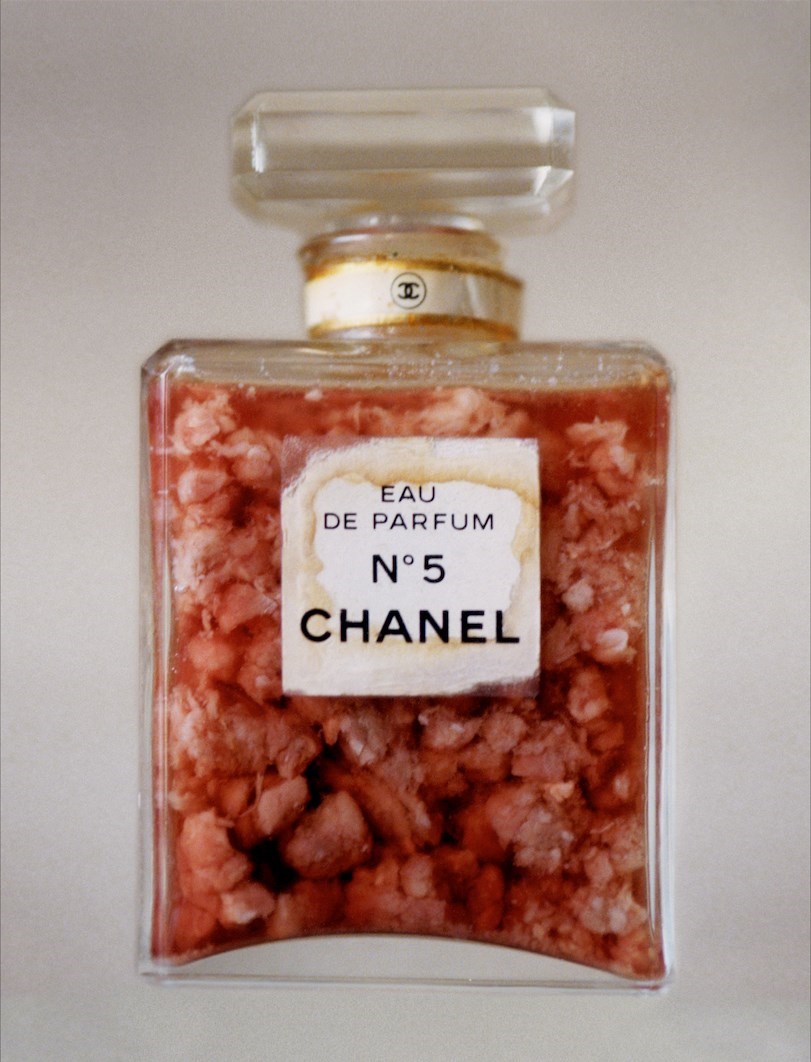

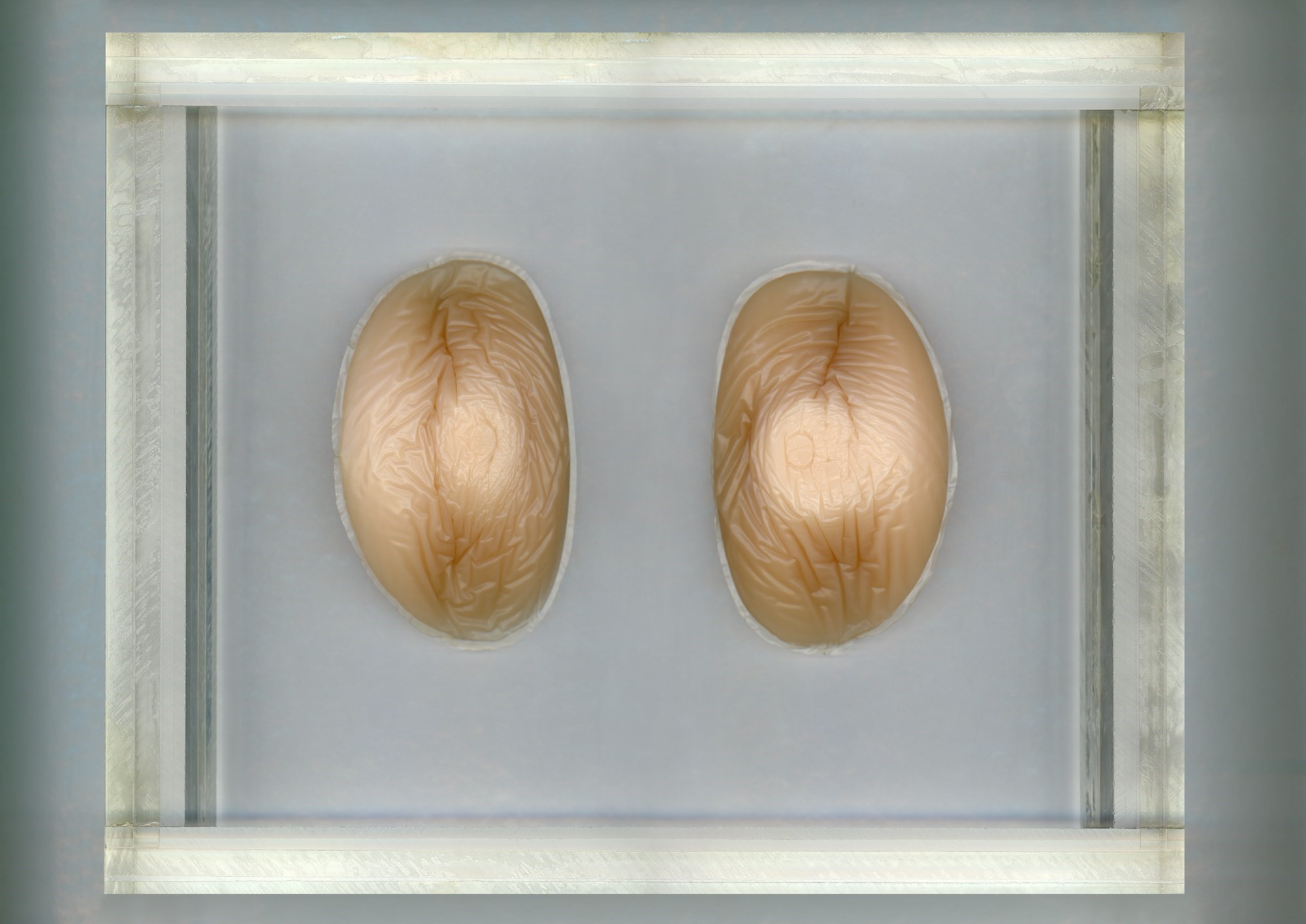

These images were scans, and they were remarkable. Made with excruciating slowness with a number of passes of a hand-held scanner (which Jebb then later stitched together in a computer) they had a weight of gaze which compelled attention. It wasn't just that they were rich in detail. That was a pleasure, it's true, and it suited the heavy embroidery of the Arlésienne costume very well. Richer than that, though, was a remarkable discovery about depth of field. Scanners are made to see flat things with great clarity. Beyond that, they don’t make much of the world. Operate one with its lid open, and it becomes myopic, struggles to discern anything beyond the few very precise millimetres it's focused upon. The result is that objects float in a haze, which acquires very strong metaphorical readings. The haze might be memory, or it might be a degree of uncertainty about the thing photographed, or it might be a poetic blank, an invitation to dream.

That technique is one central key to what Katerina Jebb has done. She manages to balance the technical – even clinical – character of her peculiar medium with her own human artistry. Her scanning reminds me of windsurfing. It's fancy engineering, but take away the human and it collapses, goes nowhere. You could say Jebb's scans look like this or that: her portraits, arrived at by very different means, do remind me of the wonderful refusal to be instant of Richard Learoyd. They do have some of the fascination with shifting technology that has enchanted David Hockney for so long. But Jebb's pictures are couched in a language both all of her time and all of her own.

She works often with fashion houses, without ever becoming their servant. She has something of the archivist about her, and loves to catalogue objects and relics. She has catalogued the things left by the artist Balthus, loves the stacks of the Musée Galliera in Paris (the museum of the history of fashion, where she has made remarkable work), even started a series on artists' telegrams. It's not surprising that she has agreed, many times, to make pictures of shoes or bags or jewellery, the staple currency of the brands. She thrives on collaboration and has accumulated a remarkable portfolio: Comme des Garçons, Hermès, Lacroix himself of course, many others. It's work, but she refuses steadily to identify herself as a fashion photographer. She once called herself an 'underground artist' when I pressed her to explain a little of how she saw herself. Even when, in the summer of 2015, she made a set of scans of the season's clothes for the shop windows of the Galeries Lafayette, she did them as works of her own and not a job of the industry's. It's a fine balance. Maybe one can say she works with the industry, not for the industry.

There is another key in Jebb's work. However she works, in film, making imagery for record covers, more commercial or more 'artistic' (are these things really antithetical?), she always takes a woman's view. It's not just a principle. It's the full expression of her personality. Women like working with her, and she has had a very fruitful interaction with numbers of women artists and collaborators. As far back as 2008, in a show also at Arles, also curated by Lacroix, there was a remarkable duet between her scans and Nancy Wilson-Pajic's photograms. She has done this again and again. She thinks, as she explains, with what she is. And if that means she thinks like a woman, so be it. She embraces that. She doesn't make pictures that aren't her own.

This year at Arles she has another show, a bigger one, almost a retrospective. Because it is at the Musée Réattu, and therefore associated with the festival without being a part of it, the show is open longer than the usual weeks of summer. It doesn't come down until the end of 2016. In that show is an unforgettably moving room. It's a medieval priory, and high in the rafters is a dark space lined with Jebb's looming scanned portrait heads of women, again approximately life-size. They have something of the Renaissance, like those portraits on medals whose relief is not quite high enough to see details in full. They carry distortion to take us away from literal photography, while holding on to enough clarity to keep us anchored in the real. They are feminine, affectionate, unsentimental, exquisitely composed and lit, and they give rise to much thought.

Katerina Jebb, Deus Ex Machina, is on view until December 31, 2016.

Katerina Jebb will be signing copies of the accompanying tome to her exhibit at the Comme des Garçons Trading Museum, 54 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honore, 75008 Paris from 6pm-8pm on September 15, 2016.

With special thanks to Katerina Jebb and Professor Francis Hodgson.