His signature blue was a key influence in Céline's S/S17 show, and a major retrospective of his work is currently on display at Tate Liverpool: here, we uncover the makings of a true artist and innovator

Italian writer and painter Dino Buzzati called Yves Klein ‘Imp’, ‘Puck’ and ‘Peter Pan’ after meeting him in Paris in 1957, where he fell victim to a characteristically surreal performance by the artist. Klein held a Plexiglas box filled with sheets of gold leaf, which he passed to Buzzati. He then wrote a receipt “for 20 grams of gold in payment for a zone of immaterial pictorial sensibility”. The two traded; Buzzati – as instructed – burnt the receipt, and Klein released the shining stream of gold into the Seine. Buzzati was dumbfounded by this “deliciously spiritual and absurd ritual”; as Klein had planned, his audience was amazed by the immaterial.

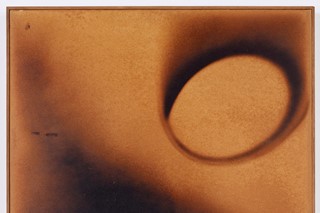

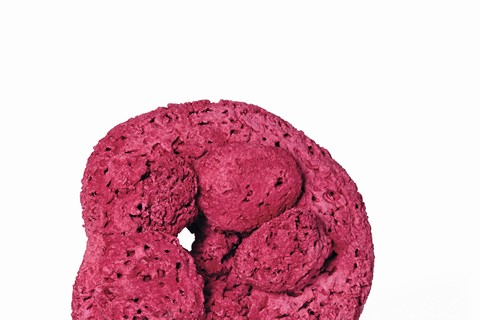

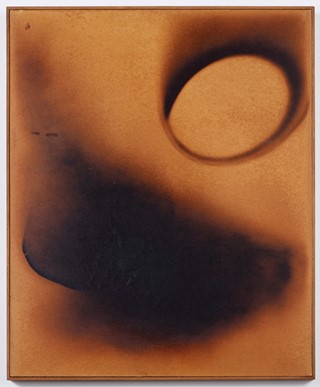

This autumn Tate Liverpool brings together major works from Klein’s self-proclaimed ‘ashes’, many never before seen in the UK, to bring the same sense of bewildered disbelief as Buzzati experienced that day 60 years ago. Tamar Hemmes, the assistant curator, observes that Klein’s focus on the immaterial is a vital aspect of his practice, the exhibition highlighting “his aim to revolutionise our perception and experience of art”. Fire paintings created using flamethrowers sit alongside planetary reliefs and monochrome paintings. Hemmes notes that Klein “aimed to remove himself from the work”, opting for distancing techniques ranging from using rollers to apply pigment, to choreographing others to apply paint in his stead (in Anthropometries). It seems ironic that despite these efforts, it is Klein’s presence that most informs his paintings – described by the artist as “poetic moments” filled with “poetic energy”. Despite the brevity of his career – he died at 34 – he was one of the most experimental and innovative artists of his time, as the Tate’s exhibition duly enforces. Here we examine the foundations of one of the art world’s true avant-gardes.

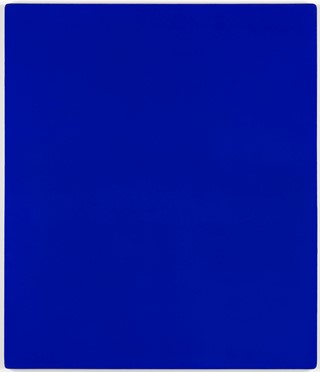

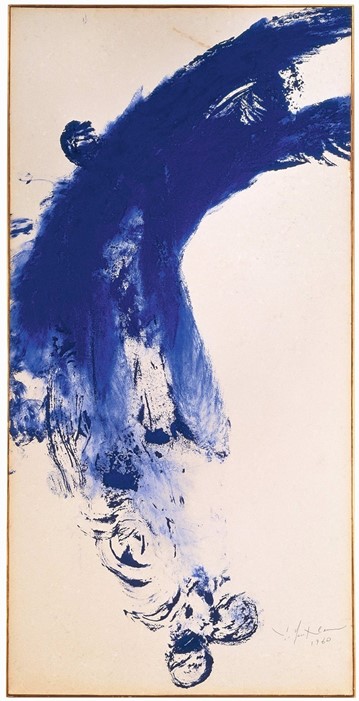

1. Colour

Colour was a crucial element in Klein’s work, particularly his invented colour ‘International Klein Blue’ (IKB), which he prepared and ground himself. He wrote beautifully on his famous monochromes, describing “each nuance of a colour” as “in some way an individual, a being who is not only from the same race as the base colour, but who definitely possesses a distinct character and personal soul”. From his first declaration to friends on a beach that “the blue sky is my first artwork”, Klein went on to appropriate many objects with his new shade, from sponges and sculptures to women’s skin.

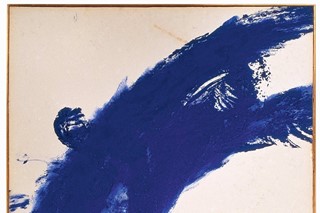

2. Painting as Performance

Klein released 1,001 blue helium balloons in St-Germain-des-Près for his solo exhibition in 1957, making it clear that he relished surprising his audience. Drama in all its forms radiated throughout his oeuvre, most notoriously in Anthropometries, where women painted their naked bodies before an audience while a small orchestra played a Monotone Symphony, composed and conducted by Klein. His use of ‘human paintbrushes’ remains controversial even today, yet he paved the way both for a new kind of performance art and a new kind of painting. In Klein’s own words, his practice saw the human body become “the theatre of the world”.

3. Spirituality and Magic

Klein was raised Catholic, and spirituality remained a central element of his work and a key theme throughout his life. He adored magic, was interested in Zen philosophy, and was obsessed with the arcane rituals of the mystical Rosicrucian society. A knight of the Order of the Archers of St. Sebastian, Klein was particularly devoted to Saint Rita of Cascia, the patron of impossible cases. Before his first show he even flew out to her shrine in southern Umbria to pray that she would protect him from his own “dangerous rituals”.

4. Travel and Exploration

Exploring other countries and traditions was important to Klein. He travelled all over Europe, and in 1949 moved to London for several months. While there he worked in a framing shop on the Old Brompton Road, where he first assisted in the preparations of colours. In early 1952, a few years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he travelled to Japan. Despite arriving at a time of immense difficulty, he stayed for 15 months. Klein returned to France a master of Judo, even writing a book on the sport, but after his foreign qualifications were rejected he returned his attention to art.

5. Self-Fashioning

Klein was the son of two artists, and as such he was conscious of the power of identity from a young age. He became a publicity machine, always aware of the influence of the press and public presentation, and quickly learned how to entertain an audience and please a crowd – features which inevitably became important in his own art practice. He regularly commissioned photographs and circulated images (notably by Ida Kar) in order to present very specific versions of himself, whether as a “visionary showman” or a “judo master”; Klein always ensured his life, as well as his art, was documented for all to see.

Yves Klein runs until March 5, 2017 at Tate Liverpool.