The Berlin-based artist has built her practice around interrogating the notion of identity through art, as her expansive new exhibition at the Baltic demonstrates

Exhibitionism sometimes feels like a dirty word: but what if that exhibitionism is in the name of art? Would you, say, use a toilet right in the middle of a busy London street, seemingly in full view of the suits and students and any other Tom, Dick or Harry strolling past? Would you feel comfortable using a toilet if it’s explicitly positioned as art? Or is it too sacred? What’s the price you’d pay for being caught short? These and so many more questions are the ones posed by Berlin-based, Venice-born artist Monica Bonvicini. In the case of the toilet, this was in her work Don’t Miss a Sec, a lavatory with two-way mirror glass which meant that from the inside, you could see everyone outside, yet they couldn’t see you. It opens up the potential to be both a thrill and utterly shameful.

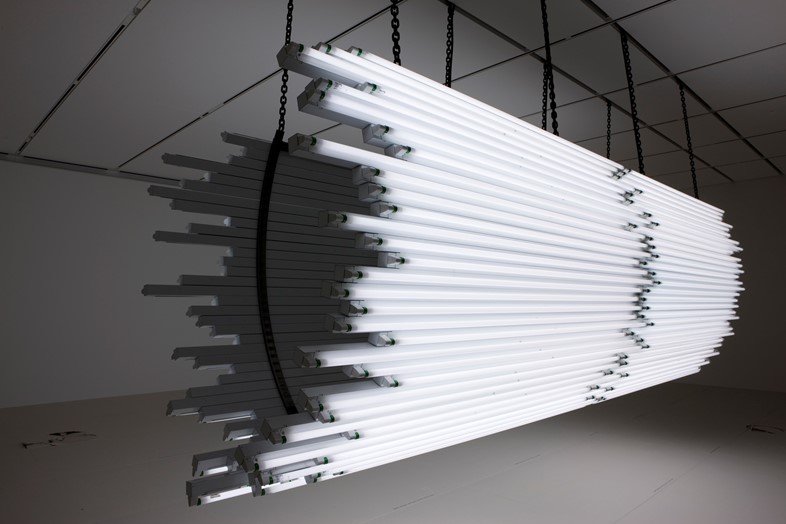

Don’t Miss a Sec is perhaps the most famous of Bonvicini’s works, and thematically it’s very similar to much of the rest of her oeuvre, which uses large architectural structures to examine ideas around the body, sexuality, and how we relate to cities and buildings. Other pieces, such as the vast light work Light Me Black, deliberately overpower the viewer in a different way, by using such brightness that it feels almost debilitating. This month, a major survey exhibition of Bonvicini’s work opens at the Baltic gallery in Gateshead, presenting sculpture, installation, video, photography, text and drawing works across two floors from throughout her career. We spoke to her about confrontation, reflection and how buildings shape our sexual identities.

On the links between sexuality and architecture...

“Architecture defines our identity. Books like Discrimination by Design by Leslie Kanes Weisman really opened my eyes to how much urban architecture influences us. The home you grow up in, the city you go to uni in and start living your life in… it’s definitely these things that define your identity, including your sexual identity. Is that city right or left leaning? Is it dark at night? How a city defines perversions and the physical environment is still an important issue.”

On confrontation in her work…

“I’m totally afraid of confrontation, but in my work I can be very confrontational as it’s not really about me. I do things I like to look at, or that I’d like to see somewhere but I don’t. Working with installations and architecture is quite natural to me, and I think it can be confrontational as it has a lot to do with reality and reality isn’t hidden, it’s up in your face. I think that the political attitude I have towards art is that it can make you think, and even more now than ever you need to be heard and seen. My piece Light Me Black for instance [a 2009 piece which overpowers the viewer with light from bright white fluorescent tubes] was for the Modern Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago built by Renzo Piano, and looks at what dialogue art can have with architecture when architecture is so much bigger, more powerful and more expensive.”

On the performative aspects of her work…

“I’ve never actually performed, as I’m too shy, but once in São Paulo I had four actors doing a play. Maybe it was a performance, but it felt more like a short theatre piece. The interaction between the viewer and my work is more to do with the 90s and the political ideology that you should interact, and not just look at something beautiful and feel intimidated. When you touch something, sit on it, use it, you understand it in a very different way. I like the communication and discussion between a viewer and the work I make. I use a lot of reflective surfaces partly because they initiate a performance when people get reflected in them, even if people are not aware they are performing and being seen doing it.”

On what to expect from the show at the Baltic…

“On one floor I’ve designed a large space that you walk into with different corridors and rooms inspired by how a darkroom works. You have to make decisions about whether you go left, right, or straight forward, without knowing what to expect. In a darkroom like the ones in a gay club you don’t know where you’re going, but it’s not like a labyrinth where it’s about finding your way out. Instead it’s about losing control in your environment.

I’m showing works from the 1990s until today, and I’ve never really put them all together in this way, I’m very excited about it. Most of the pieces have an S&M-like aesthetic and in their totality they remind you more of the idea of dwelling – not really living, or about an apartment, but the idea of constructing a place where you build your identity.”

Monica Bonvicini: Her Hand Around the Room runs until February 26 at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art.