As Lindbergh unveils his pared-back interpretation of the Pirelli calendar for 2017, we publish an interview with the legend himself at the opening of his Kunsthal Rotterdam exhibition

Last week, the 2017 edition of the world famous Pirelli calendar was unveiled in Paris. Titled Emotional, it showcased 40 un-retouched black and white portraits of prolific actresses, who range in age from 28 to 71 and are – for the most part – fully clothed. Kate Winslet, for example, bares only her hands, while Uma Thurman confidently faces the camera, a mass of freckles and towel-dried hair.

Given that the series upholds a subtle, painterly quality and an honest portrayal of its sitters, it should come as no surprise that it was lensed by veteran photographer Peter Lindbergh, who, aged 71, offered a powerful riposte to the calendar’s archetypally nude and exotic shots, instead expressing his desire to show “real women”. This time the calendar “reveals another kind of naked, more important than body parts,” he added.

Of course, this very notion of exposing a deeper, more truthful beauty – one that places personality and emotional frankness over artificially enhanced glamour – has continued to inform the German image-maker’s three decade-strong career. And in turn, his honest, predominantly analogue photographs have made an indelible mark on contemporary fashion and pop culture.

Let us not forget that it was Lindbergh who, in the mid-1980s, explained to Alexander Liberman [the former editorial director] of American Vogue that he simply couldn’t relate to the images of overly styled women that the magazine featured (much to the title’s dismay). Several years later, when Liberman exited his role and Anna Wintour took to the helm, Lindbergh tried again – and this time he succeeded. In fact, he shot the cover of the November 1988 issue of American Vogue, depicting the radiant Israeli model Michaela Bercu in a cropped jewelled Christian Lacroix jumper and stonewashed jeans. Captured mid-flow on a busy New York sidewalk, her eyes are closed, her head is turned away from the camera and she appears to exhibit a genuine smile. At the time it was a revelation, signalling a move towards an uninhibited, pluralistic beauty that women might feel more inclined to relate to.

This, and many more of Lindbergh’s photographic landmarks, are currently on display at Kunsthal Rotterdam, as part of a dedicated retrospective exhibition of his genre-defining works in Peter Lindbergh: A Different Vision on Fashion Photography, which shares its title with an accompanying Taschen monograph. “I spent three years working inside the Lindbergh archive in order to edit some 10,000 photographs down to just 220,” revealed the show’s curator Thierry-Maxime Loriot, “and I now love his work even more. He is an artist who has strong values, strong social messages and great humanity – which you will find in his images.”

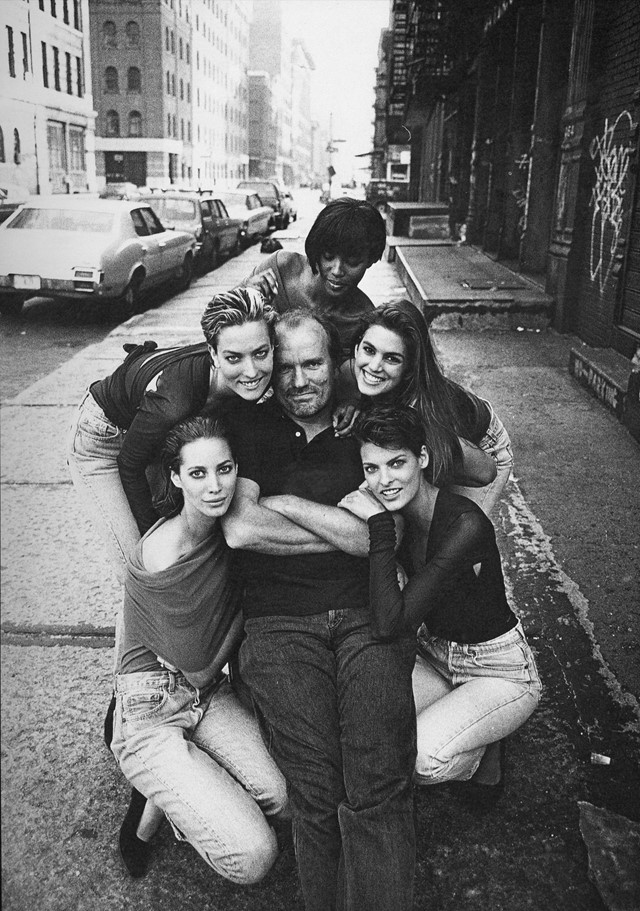

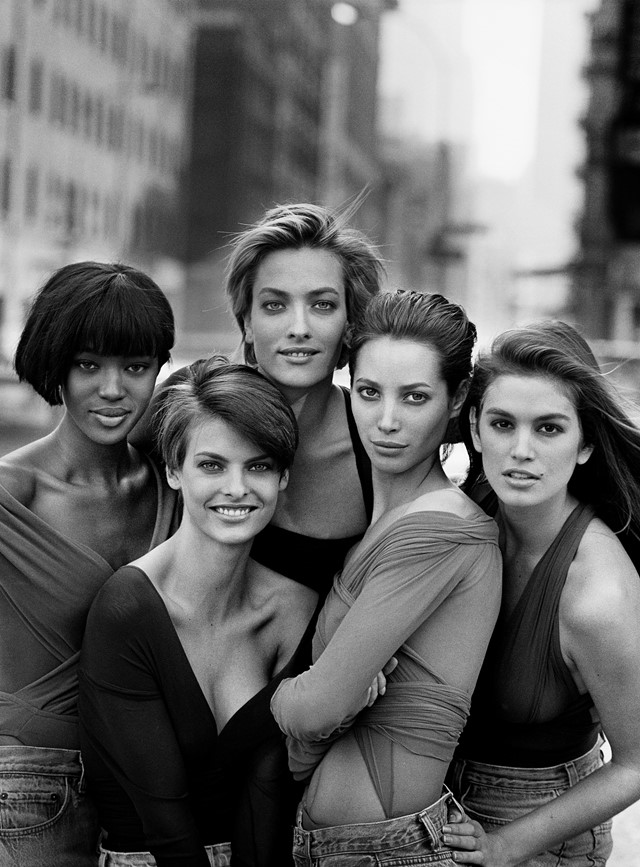

Organised thematically across nine rooms, the exhibition demonstrates Lindbergh's unique aptitude for using fashion to talk to, and about, women, through scribbled-on storyboards, Polaroids, personal notes, contact sheets and spectacular, large-scale prints. And while he has been the subject of many a fashion exhibition over the years, this show really does provide an unparalleled insight into his opus. Even Lindbergh himself, who is charming but famously straight-talking, seemed touched. “I could have never imagined this, it really is quite something,” he told AnOther at the exhibition’s press preview. “There is a whole lot of history in these photographs.” I reference his game-changing 1986 ‘white shirt’ shoot, which depicted a group of supermodels including Christy Turlington and Linda Evangelista, washed up (elegantly) on a sandy beach, wearing nothing but crisp white cotton shirts. “You know, those pictures were actually refused [by American Vogue] at the time, and we were all really upset about that,” he confessed. “I think they were just six months ahead of their time – it was too natural then.”

For a man who has spent a large portion of his life photographing some of the world’s most influential talents – from Tilda Swinton to Azzedine Alaïa, Charlotte Rampling and Kate Moss – he freely admits that he despises being in front of the camera himself. “I’m telling you, I just absolutely hate having my picture taken – I don’t like just standing there not really doing anything,” he said. He does, however, “continue to take regular self-portraits” as part of his creative practice.

Having had the pleasure of viewing Lindbergh’s powerful oeuvre up-close, it’s clear that his images have an enduring quality which, unlike today’s transient digital photo trends, renders them timeless. The S/S98 campaign he lensed for Comme des Garçons, for example, which was shot inside a factory (industrial backdrops remain a constant in his work) looks as current as the intimate, beautifully lit portraits of Alicia Vikander that he took for W magazine just last year.

One of Lindbergh’s current muses, Dutch supermodel Lara Stone, who accompanied him to the exhibition opening (clad in a white cotton shirt – a nod to his legacy), surmised her experience of working with the photographer rather aptly: “I just so desperately wanted him to love me, that what I didn’t expect was for me to fall completely in love with him right from the start.”

Peter Lindbergh: A Different Vision on Fashion Photography runs at Kunsthal Rotterdam until February 12, 2017.