40 photographers from 17 different countries feature in Charlotte Jansen's new book about the female gaze: here, she introduces us to ten of them

The front page of the Daily Mail newspaper last week featured a photograph of two of the UK’s most powerful political figures, the prime minister Teresa May, and Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon. The headline screamed: “Never mind Brexit, who won Legs-it!”

Obviously, the outrageous front page – and the accompanying article by Sarah Vine – has been slammed as sexist, but what about the photograph itself (taken by Reuters’ Russell Cheyne?) If the headline text had been different, would we have read this picture any differently? The history of depicting women’s bodies as objects of heteronormative desire is so long-established and so widespread that our eyes are trained to pick up the cues, to survey the sexual appeal of any woman who appears in an image. In photography, this is particularly problematic, since nearly all the photographs of women we come across are trying to sell us something. If we cover the words, what do we really see in this photograph? Two powerful political figures? Or two women, with nice legs? We’re more familiar with the latter view.

Three years ago I started researching the photographs women have been taking, of themselves and of others. I interviewed 40 women from 17 different countries about their work, and these artists now feature in a book, Girl on Girl. Whether working in fashion, advertising, photojournalism, or art, I learned that women photograph women differently to men, and that women see far more than a female body when they point their camera on one.

Photography has a huge influence on us, and the fact that more women than ever are now getting behind the lens is significant, because we are seeing things about ourselves we’ve never seen before. Until now, most of the images of women we’ve been exposed to have been created by, or for, men. This is the beginning of the age of the female gaze.

1. Deanna Templeton

Deanna Templeton has been taking photographs since she was a teenager; at punk shows, skate parks, on the streets and at the beach. During the 1990s and 2000s, if Templeton hadn’t been taking pictures, there would be few documents showing how girls have been part of the skate, punk and surf scenes in California. Her ongoing, expanding portrait of women is tender and timeless, and she is clearly drawn towards women who she feels connected to – women on the cusp of realising their power: “a lot of the young girls remind me of myself when I was young, or how I wish I could have been,” Templeton told me. She’s long overdue an in-depth survey, and I really hope she will get one soon.

2. Maisie Cousins

“I’d probably be a vandal if I hadn’t had Instagram,” Maisie Cousins told me when I visited her at home to talk about her work. At school her teachers didn’t ‘get’ her art, but she kept going and made her own success. Inspired by the photography in vintage cookery magazines, among other things, Cousins’ work is sensory and sensual and her bodily compositions say something far more truthful about bodies than the usual photographs we find in magazines. She combines classicism with the high gloss of fashion magazines, but her images aren’t clean and neat; they visualise the messy relationship between indulgence, consumerism, and our bodies.

3. Isabelle Wenzel

Isabelle Wenzel’s work – also the cover image for the book – is, in my mind, the perfect visualisation of the female gaze. Wenzel’s photographs at first might appear as though they’re concerned with femininity, or feminism, because we see a female body before we see anything else, reinforced by the high heels, tights, and teacups Wenzel tends to use. But Wenzel isn’t interested only in the female body – she just happens to inhabit one, and this is what she uses in her spontaneous photographs which mix design, sculpture and architecture with photography, something like Erwin Wurm’s one-minute sculptures. She understands space and form intuitively – as she puts it: “My body organically knows what to do, in a way that the camera becomes almost like an extension of it, a synthesis of man and machine.”

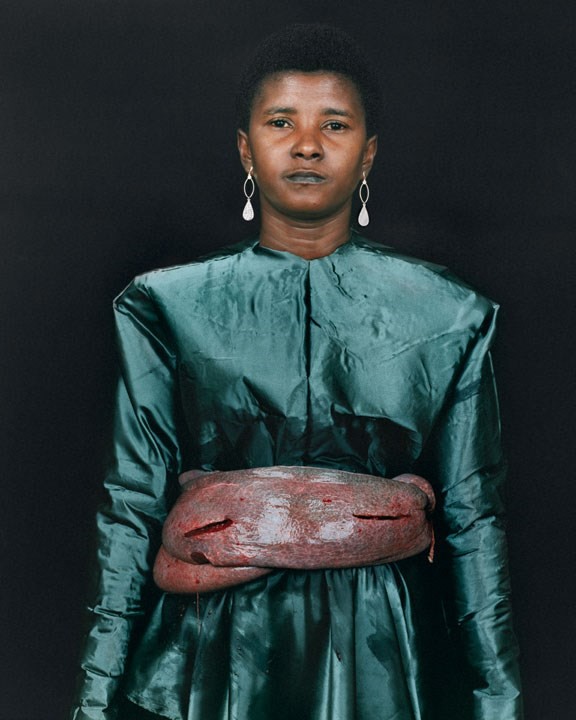

4. Pinar Yolaçan

Turkish-born photographer Pinar Yolaçan takes years to complete her series of photographs, which makes her unusual for a young artist. Yolaçan graduated in fashion from Central St Martins but then turned to photography, creating handmade costumes from meat, latex, fabric, or paint for her subjects. Her long process begins with getting to know the women she photographs, from those living in remote Candomblé communities in Brazil to BBW models in Los Angeles. Again, Yolaçan doesn’t see her work as feminist in the strict sense; she looks at how we treat bodies and flesh in art and photography, and as a woman, it’s only natural she should be interested in those of women, and what happens to them.

5. Yvonne Todd

Yvonne Todd was one of the most exciting discoveries for me in putting together Girl on Girl. Based in New Zealand, Todd’s work hasn’t yet received the recognition abroad it deserves. Her photographs – some in which she appears, others featuring models – are among the most unsettling and memorable photographs of women I’ve ever seen. Todd’s not empathetic towards her consumer addicted characters, but her criticism cuts deeper – we’re all part of this warped capitalist world, and women are both the victims and the perpetrators of it.

6. Phebe Schmidt

Also dealing with capitalism and consumerism – while simultaneously shooting for brands – Schmidt uses a really interesting visual language which is so different to that of women selling us stuff that we’re used to seeing. From the models she uses, to the way she juxtaposes discordant objects (eggs, butter and cheese with high fashion accessories, plastic bags with perfect beauty) Schmidt creates an ‘un-realism’ which erects a far more truthful reality than the airbrushed version of it we’re accustomed to.

7. Juno Calypso

It’s hard to miss Juno Calypso’s work – the London-based photographer has become one of the biggest names in contemporary photography in the past year, exhibiting from London to Lagos, and she’s still only in her 20s. What I like about Calypso is not only her extreme care in constructing her images – she famously shot her most recent series on solo romance at a love hotel in the U.S. – but the fact that she refuses to overproduce. It’s rare to find an internet famous artist who holds back like Calypso does, carefully considering every work she creates.

8. Marianna Rothen

When women want to make women beautiful, they know how to do it devastatingly well: Marianna Rothen’s female characters (some herself) are not just seductresses, however – they are complex heroines, caught in the midst of some turmoil, inspired by the protagonists of film noir, exploring the female gaze in cinema and photography. “I like my women to be more iconic than realistic. Showing something bluntly to me doesn’t have the same potential for narrative,” Rothen explains. Her narrative frames the question: who is looking? And at what?

9. Petra Collins

The biggest name to emerge from photography since the introduction of the front-facing camera is undoubtedly Petra Collins. What’s so interesting about Collins, on top of the fact that she knows how to take a good picture (she cut her teeth assisting Ryan McGinley), is that she’s introduced feminism to a generation of teens who might not have thought it was cool before. Love or loathe her, Collins is here to stay, and she’s going to be shooting a lot more of the photographs we see around us in years to come. Following in a long line of male photographers who document their own generation, it’s about time a woman took the lead.

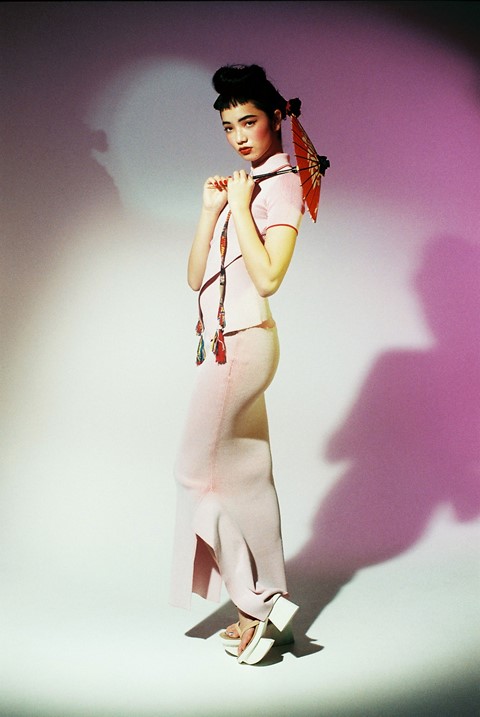

10. Monika Mogi

A young photographer working between New York and Tokyo, Mogi mixes work in fashion, advertising and art, and is one of several practitioners influencing a shift towards the female gaze in our day-to-day lives. Her work in the Japanese context is particularly rare and important, making an effort to cast all kinds of women, and to create images which don’t pander to stereotypes. It’s very obvious from Mogi’s photos that she has a good time with her subjects, and that sense of female-centred fun is a glimpse of women’s world, free from the male gaze.

Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze is published by Laurence King and available now.