Central Saint Martins graduate Anja Aronowsky-Cronberg started her career as editor of Acne Paper, the review published by the Swedish brand Acne.

Central Saint Martins graduate Anja Aronowsky-Cronberg started her career as editor of Acne Paper, the review published by the Swedish brand Acne. Since then she has moved on to curating programs for biennals and to editing Vestoj, a review on sartorial matters, that connects intellectual strength and aesthetic refinement. Vestoj’s upcoming issue, published at the end of this year, will deal with the issue of shame in fashion.

How would you connect fashion to elegance?

I find the division between fashion and elegance a bit frustrating. It’s very common to hear people say things along the lines of: elegance is something eternal and timeless, whereas fashion is this dirty business that changes constantly. But I think that kind of view forgets that elegance is just another form of fashion, albeit one that changes more slowly. The little black dress, that people often refer to when they talk about elegance or style, is something that has been in fashion for maybe ninety years, whereas a t-shirt hanging on the racks in Topshop, might be desirable for maybe three months. But what difference does it make in the long run, when all things are eventually ephemeral?

What is the role of history and art history in your conception of fashion?

Fashion is a part of art history and, as such, of history. If you read art history as a history of the different expressions of culture you could perhaps describe it as a sort of overarching umbrella, under which fashion fits well. Both are expressions of our time.

Would you describe fashion as a language and a discourse, as Barthes did ?

To me, it seems almost arbitrary that Barthes decided to focus on captions in fashion magazines. I imagine that for a philosopher and linguist this vernacular must have been almost irresistible in all its non-sequitur weirdness; I suspect that this is what attracted Barthes, rather than fashion as such. But if you talk about fashion as a language in general, rather than in relation to Barthes, I would say it has more to do with communication, with being in a room full of people and selecting who you would be the most comfortable talking to, the person who looks the most like yourself, or that you feel the most familiar with. In contemporary capitalism fashion is a tool in the creation of our identity, and as such a quite potent language I think.

The word "intellectual" was coined in a time of great political distress. Does fashion have a political role? And in which way?

Of course fashion is political, although not necessarily in a Katharine Hamnett political t-shirt wearing kind of way. Today, everybody knows about the abysmal working conditions that the fashion system implicitly supports, yet we continue to put distance between ourselves as fashion consumers and the dire production conditions of much of our goods. I recently interviewed a designer producing extremely exclusive collections, with a very pure vision of making garments of the best quality and in the most artisanal kind of way. It struck me that on the one hand you could say that this kind of production and consumption is something that you could engage with in a somewhat ethical way, by consuming restrictively and only garments locally produced. But on the other hand the garments were so exceptionally expensive, precisely because of the way they were produced, that your choice inevitably becomes political again; the only people who can afford to buy these sorts of garments are the very rich. With fashion we are always in a double bind, capitalism relies on consumerism, over-consumption arguably, to function so of course whenever you deal with a consumable good, it’s going to be political. Whether it’s a level of politics we want to engage with or not, is, of course, a different story.

How would you relate the concept of fashion to the one of style?

As I was alluding to earlier, I think that style, as well as its sister term “elegance”, are simply different expressions used when describing the way we relate to fashion. Often I find that “style” is used in some sort of almost self-congratulatory way, as if it is a better or more honourable way of dealing with fashion. In the end though, both the fast-paced trends of fashion and the more slower-paced changes in style are equally malleable. Ultimately everything always changes.

What does fashion have to do with intellectuality?

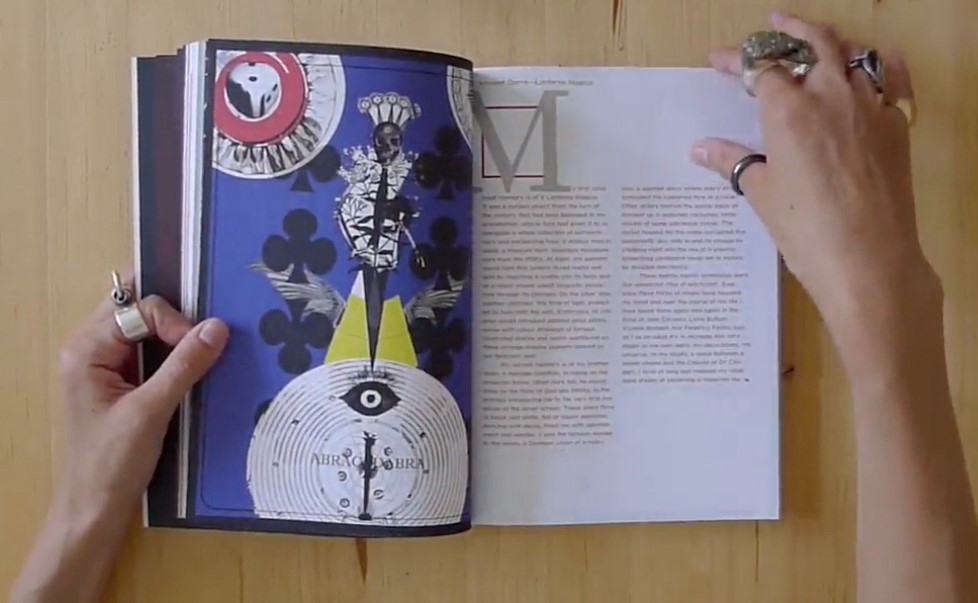

Everything or nothing really. Fashion can be appreciated on purely aesthetic terms, but as an expression of creativity or as a form of contemporary culture it is always open to intellectual interpretation. What I see as the purpose of my work and of Vestoj is to ensure that images and text are always somehow in dialogue with one another, that the creative mind meets the scholarly point of view. I’m not saying that fashion has to be intellectual, but I do feel that it is, more than perhaps any other form of contemporary culture, so symptomatic of where we are at right now – it talks about voracious consumption, this almost decadent need for pleasure that we have today, and about the speed with which we live. Not to analyse it, be it intellectually or creatively, would be kind of ludicrous.

Vestoj, the review you edit, is designated as a Journal of Sartorial Matters – what kind of relation would you see between the sartorial aspect of it and its intellectual approach?

I’m trying to take an intelligent and multi-facetted approach to sartorial matters. What I find the most interesting methodology is the one that deals with both the production and consumption of a garment, as well as with the analysis of it. There are journals out there written by and for academics, but they often don’t have much impact on the industry. And then you have lifestyle and fashion magazines that fit fashion in with all aspects of contemporary culture – film, music, art, celebrity and so on. What I want to do is produce a magazine that deals only with clothing, fashion, dress, style, ornament or whatever you want to call it, where every single page is dedicated to understanding this phenomena a little better.

In your editorial work, you pick themes, such as nostalgia, memory or shame, and then you see how they relate to fashion. Is fashion some sort of cornucopia for contemporary thinking?

That’s in fact what I like so much about fashion. You can view it, analyse it, under almost every lens under the sun. Through the study of fashion you can understand any given point in history, our desires, ideals, wants and needs. The aspect of fashion that deals with voracious consumption has spread into every way we relate to culture; today we consume ideas, knowledge and people as much as we consume goods. Fashion in that sense is nothing short of a Gesamtkunstwerk.

In two weeks Donatien will be interviewing the designer Rick Owens who is also featured in the latest issue of Another Man A/W11.