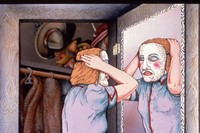

Suzan Pitt’s image of a woman fellating an asparagus plant in her 1979 animation Asparagus seared itself on to the minds of anyone who’s seen it, and is one of the most joyous scenes in film. Sure it’s humorous, yet it appears like an alarm bell in

Suzan Pitt’s image of a woman fellating an asparagus plant in her 1979 animation Asparagus seared itself on to the minds of anyone who saw it, and is one of the most joyous scenes in film. Sure it’s humorous, yet it appears like an alarm bell in a surreal world deep with meandering bleakness – it is fitting that the film’s first tour was with David Lynch’s Eraserhead. As with most of her films, Pitt brings together odd dichotomies of mood and colour; bold, bright tones illustrating desperate, lonely characters caught in a milieu of crises.

Pitt is currently in the UK with her new film Visitation, which premiered at the Flatpack Film Festival in Birmingham. Visitation is certainly her most abstract film to date, departing further from the narrative found in her other work. Though it shares the arresting emotional jolts of El Doctor (2006), being shot entirely in black and white only underlines its lack of playful humour.

Pitt taught herself animation in the 1960s from a book she found in the library. Having lived in the Lower East Side during the 70s, in 1988 she moved from New York to teach at Harvard. She currently teaches Animation at California Institute of the Arts. While animation has been overhauled in the digital age, Pitt’s films are all still painstakingly and beautifully hand painted. Here Pitt talks to AnOther about where her images come from and her interests in Asparagus...

"The ideas for the movies just happen inside of me as I move around inside of the world."

I first saw Asparagus play when it toured with Un Chien Andalou – do you consider yourself a surreal filmmaker in the same vein?

Certainly I never think to myself: "I want to go into the world of the surreal," I never think that. If someone sees a relationship, I could sort of see why, but it’s not anything that I consciously think of. Surreal means above reality, so definitely, in that sense, my films probably all are. I really work in a between-mind area, daydreaming. I’m a big daydreamer. I love being alone and letting my mind play. We don’t let our minds play enough. My films come from when I’m walking or sitting or staring or whatever. Over time I’ve built up a way in which my mind ponders ideas.

Visitation is a lot darker than your previous films, where did the imagery come from?

I have this little cabin in the woods in Michigan that’s very remote, a long way from anybody. I was alone in the woods in the cabin reading H. P. Lovecraft – early Gothic writing, almost a better writer than Poe. It was very late at night and I heard wolves, and wolves are very rare. It’s such an amazing sound – it sends a chill down your whole body, it just stops your heart. It’s just the most primal, dark, pre-history feeling going back through time forever. And so the combination of reading this archaic early English language and hearing the wolves just came together and I thought that’s the psychic place I want to go to. When I woke up, I wrote about the eternal ballet of death and life and waiting to be born and making dreams and the alchemical desire to find and understand the nature of things. I didn’t want to actually illustrate the text, I wanted to make images that in themselves took you for a few seconds into that feeling. I also tried to make the process of the film and the materials in the film, the way I was using it, emblematic of the idea. So it was kind of different, it was a shorter film, it’s much more direct, it’s much more spontaneous under the camera.

Who were your contemporaries? Did you ever feel part of a filmmaking scene?

I lived in New York in the late 70s. There weren’t people in animation that I looked at their work and thought: "Oh that blows my mind." Later, after I made Asparagus, people became aware of me, and I in turn became aware of the films that were being made. When I met David Lynch it was at the time our films were running together. He’s rather quiet, he’s nice and that’s about all I can say about him. He’s a genius, not everything he’s made is great, but he really is a great artist. Eraserhead, to me, is one of greatest films ever made, it’s fantastic, but then that’s just my taste.

There’s a playful sexuality in Asparagus, where did that image come from?

I was incredibly depressed when I made Asparagus. I know it doesn’t look like it. It’s beautiful, it’s colourful, it’s dealing with deep themes, but I was actually in a very depressed state when I made it. So out of that I brought out what I wanted to say. Sexuality for us humans is one moment in time when you meet another human being and you grapple and you search for some kind of deep contact. There’s the pleasure aspect of course, right? But there’s something that you reach for; this incredible contact of closeness, like one thing understanding another thing, even though you never can, but in that act it feels like you can. So she’s looking to nature, she’s trying to understand the world, she’s absorbing and trying to make contact with the world, she’s inside of herself. So the sexuality is just an analogy for understating and contact.

What fascinated you about asparagus as a plant in particular?

When I was married we made a garden and I planted asparagus seeds. The first year it was like a hair, to me that was so magical. And also asparagus has a dual sexuality. It comes up and it’s very phallic looking, that’s the asparagus we know and we eat, but if you don’t cut it, it becomes a really tall, lovely, flowing, feminine fern. So it’s a creature that has two sexualities, and I really like that about it.

Suzan Pitt is appearing at London International Animation Festival this Saturday, March 31.

Text by Simon Jablonski