Born in Louisiana, Scott Campbell studied Biochemistry at The University of Texas, a discipline he soon abandoned in favour of tattoo artistry, honing his craft at the infamous Picture Machine in California; a notorious street shop which, since its

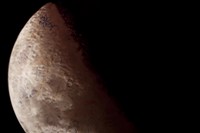

Born in Louisiana, Scott Campbell studied Biochemistry at The University of Texas, a discipline he soon abandoned in favour of tattoo artistry, honing his craft at the infamous Picture Machine in California; a notorious street shop which, since its foundation in 1976, has housed some of the world’s best known tattoo artists. Today, Campbell owns Saved Tattoo in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, but most recently, he has turned his attention from skin to fine art, carving sculptures out of money and experimenting in watercolours. His latest exhibition, They Say Miracles Are Past, details a series of lunar landscapes. Suspended in resin, each sculpture of the moon is ‘defaced’ by the language of tattoos; symbols, signs and sketches which tell narrative stories of personal experience.

On the eve of his exhibition opening, AnOther caught up with Campbell to talk about his work, tattoo artistry and why he chose to spend six weeks in a maximum security prison in Mexico City.

What inspired your current exhibition?

I made the first moon piece because I was obsessing over the texture of the lunar landscape and the craters and the 'organicness' of that. I made one and it was beautiful. The light that it reflected was so unique. But it was so pretty, so nice, that my instant reaction was to make it dumb. It was almost too nice for me to relate to. In order to make it real I had to deface it and make it my own.

Before they were encased in resin, I drew on each one – a stream of consciousness, childish drawings. I’ve always loved drawing and writing, but felt they had to be ‘nice’. With these, it was the opposite. I had already made something that was beautiful and was therefore free to be really playful with it. I would carve out each moon and just sit there with it for a week, writing on it. Each developed its own personality and evolved into its own narrative.

You said of the exhibition, “Sometimes I think the mystery was worth more than the knowing.” What did you mean by that?

It was an acknowledgement of our relationship with the moon specifically. There was a race to be the first person to stick a flag in it. We sent a missile there to see what the vibrations did and to test for water, but the moon has historically been such an inspiration for fairytales and mythology. It’s a magical thing. All efforts have gone into demystifying it and a part of me thinks ‘What if humans like having those fairytales and that mystery, more than knowing what the rocks are made of?’ I want to have magic things around me. I don’t want to know what percentage of nitrogen is in the rock. I’m a hopeless romantic.

"One of the most important things about being a tattooer is really paying attention to the emotional responsibility of the tattoo and not just the aesthetic"

What is it about tattooing that you like so much?

I like the human aspect, the emotional interpretation that’s involved. You meet someone and take their emotional situation and figure out a way to summarise it, in a phrase or a symbol or an image. One of the most important things about being a tattooer is really paying attention to the emotional responsibility of the tattoo and not just the aesthetic. It should address why that person is getting it and what the meaning in their life is at the moment.

You spent six weeks in a maximum security prison in Mexico City for a series of watercolours about the prisoners there. What was that like?

I went down there to document the tattoos that people were getting. Prison tattoos are intensely fascinating to me because prison is a community of people all dressed in orange jumpsuits, all assigned a number, all living in cages. It’s a system that does everything it can to remove the humanity from a person. Tattoos become this last-ditch effort to claim some sort of individuality; the only way you have of discerning yourself from the gang. I feel what people choose to get in the gravity of that situation is really interesting. So I went down there to photograph the tattoos for my records and inspiration. And being there, a lot of the guys really warmed up and I ended up tattooing a bunch of them. I would go there every morning and leave whenever they kicked me out. They wouldn’t let me take in tattoo equipment so I had to make the machine out of whatever I had. It was really cool – making little Frankenstein machines out of toothbrushes and walkmans and electric razers.

Do you prefer tattooing or the fine art you are currently working on?

Everyone asks if I’m still going to do tattoos and I do love them, but now I divide my time between the two. I really love working in other mediums because there are a lot of ideas that I explore, but I’ll always have tattoos in my life to some degree because there’s purity in them and no re-sell value. I like that nobody gets a tattoo because they think they might be able to sell it for more money.

Scott Campbell: They Say Miracles Are Past is at OHWOW Gallery until October 13.

Text by Edwina Langley