A new exhibition explores the life and work of the one-time beat movement footnote, who invented the cut-up technique and later became a talismanic figure

Brion Gysin is a touchstone for many contemporary artists, a one-time beat movement footnote who has subsequently become a talismanic figure. Much of his life was devoted to radical psychotropic experimentation with his close friend William Burroughs, but to understand him as Burroughs’s muse is misleading. In fact, he was an interdisciplinary artist who was years ahead of this time: a prophetic “idea machine” whose “cut-up technique” is a precursor to the dizzying information flux of modern life. Although his work spanned a wide variety of media, he is perhaps best known as the inventor of the Dream Machine: a stroboscopic device intended to allow viewers to paint pictures in their minds. Next month, Gysin is the subject of a major retrospective at New York’s New Museum. Here AnOther talks to the show’s curator, Laura Hoptman, about her intention to bring Gysin out from the shadow of “Il Hombre Invisible” and into the light.

Do you think that Gysin’s symbiotic relationship with Burroughs may have held him back as an artist?

The two were certainly joined at the cerebellum, but Gysin shines a tremendous light in his own right, especially in the field of visual art. Burroughs was an underground phenomenon and the platform for Gysin’s livelihood, but it’s true that he also shadowed him. One area of contention has to do with who invented the “cut-up.” Burroughs tried his entire life to tell people that Gysin invented the cut-up, but because Burroughs ran with the idea, producing numerous novels, he is the one credited. It’s important to think of Gysin as an idea generator above all. For instance, when Gysin created the cut-up, Burroughs would send him letters every couple of days with all these great ideas like, “Why don’t you write a poem in many different languages and cut it up?” But Gysin wrote back and said: “Know what? Collage is boring to me. I’m already on to the Dream Machine.”

Can you tell us about the genesis of the cut-up technique and the ambitious Third Mind project he embarked on with Burroughs?

The idea to equate the written word with the abstract language of painting or art-making was an innovation that Gysin began to think about in the early 50s when he learned Japanese and Arabic calligraphy. The Third Mind is simply the merging of words and pictures and the taking apart or deconstruction of them to divine new meanings once they have been put back together. It’s kind of like looking at tea leaves. Both of these guys were very interested in esoterica, and they felt there was meaning hidden in words and images that was not being allowed to come through. They wanted to reclaim consciousness from societal control. Burroughs felt it was important to get word out about the cut-up because he thought it could free people’s minds. The Third Mind book is actually kind of apocryphal. It never really saw the light of day and it now resides at the Los Angeles County Museum in bits and pieces.

Do you think they were driven by a desire to be subversive?

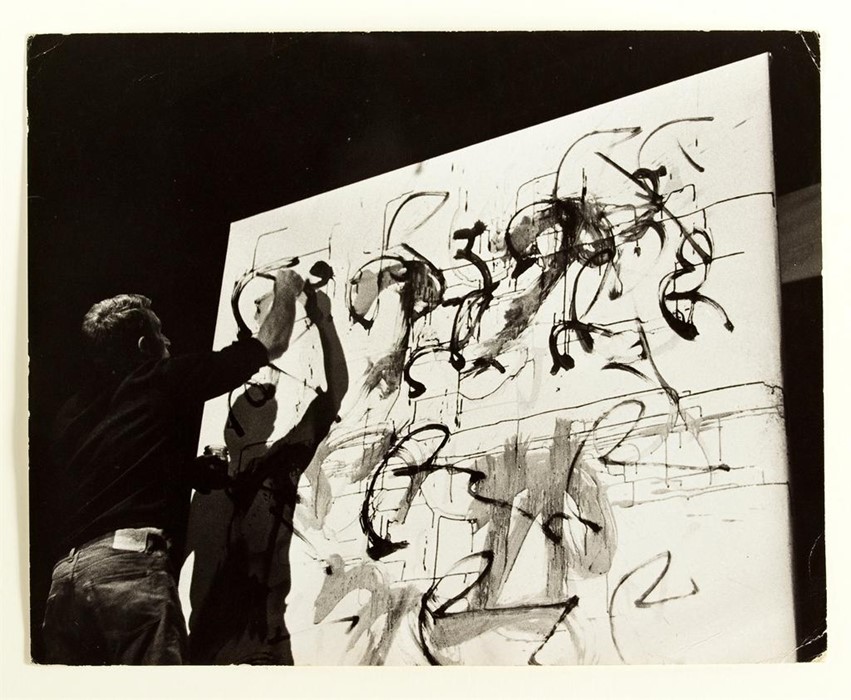

Yes, it was a choice for them. They took their energy from being counter, and I think it was enormously important for that generation to be counter to the structure of contemporary culture in every possible way. These were guys who were stateless, gay, psychotropic experimenters (and in the case of Burroughs, also a murderer and a junkie). They used drugs very consciously as tools that supposedly allowed them to get out of where they were. There is a lot of talk about cultural subversion now, but I don’t think anybody could beat these guys at that. Gysin was also interested in the straightforward notion of magic. The calligraphic style he created was a personal glyph that consisted of drawing his initials over and over again; it was, in its way, a spell.

Where do you think that drive towards transcendence came from?

They talked a lot about outer space and they had a sense of mission – a notion of being astronauts exploring new worlds. Gysin said he hoped that the Dream Machine would be in every home and replace the television, which was a wonderful idea, but I don’t think he really thought there was going to be a world revolution. Their world was a very subcultural one and they were kind of proud of that.

What made you want to host a retrospective?

I think what drew me to Gysin is the notion that the cut-up has dominated our cultural thinking now for the past 25 years – certainly since the inception of the internet. This idea of breaking down information and ascribing new meanings to what we thought were transparent symbols is something that is done daily now, and he predicted it.

Brion Gysin: Dream Machine is on show at the New Museum from July 7