If you haven’t encountered the paintings of British artist Phoebe Unwin, it’s only a matter of time. The 32-year-old artist burst onto the scene in 2007 with a solo show at Milton Keynes Gallery that had everyone, including Charles Saatchi, talking.

If you haven’t encountered the paintings of British artist Phoebe Unwin, it’s only a matter of time. The 32-year-old artist burst onto the scene in 2007 with a solo show at Milton Keynes Gallery that had everyone, including Charles Saatchi, talking. Now her paintings are on view at Wilkinson gallery and at the Hayward, where British Art Show 7, an exhibition showcasing the works of the UK's most ambitious talent, opens tomorrow.

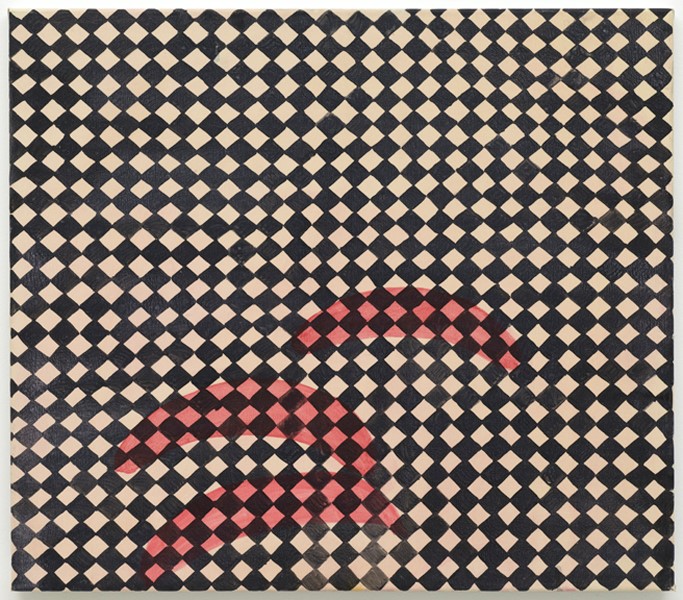

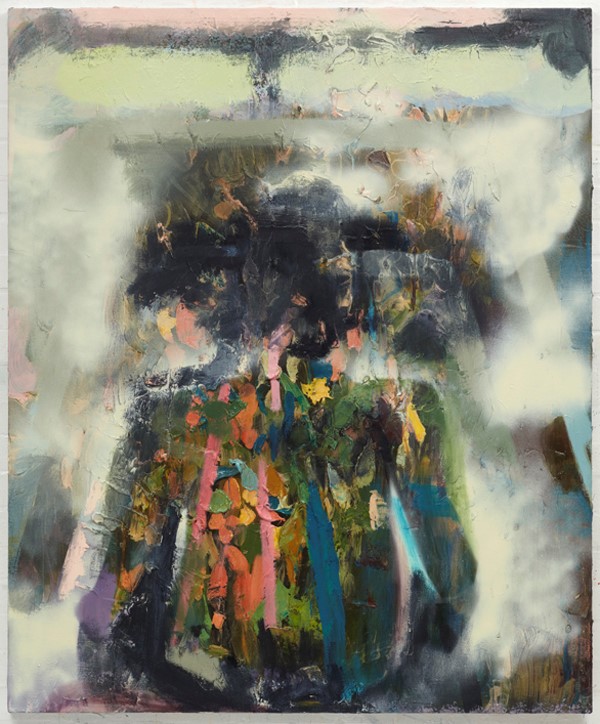

Working solely from her imagination, Unwin’s paintings often bear the playful quality of a child’s tribute to a beloved place or person left behind. This speculation may not be so far from the truth, according to Unwin, whose spectacular palette reflects the colors she discovered while growing up in California and Cambridge: figurative and abstract forms are rendered in eye-popping flamenco pinks, sorbet yellows and somber grays, a colour scheme which complicates our reading of these works as mere whimsical expressions. Here, Unwin talks to AnOther about her approach to colour and painting.

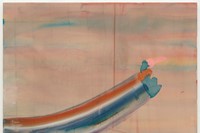

I understand that you paint from memory, preferring not to use photographs. Why have you chosen not to rely on physical source material and how, then, did you go about creating a work like Key?

I find memory a useful editing tool in the sense that it cannot isolate image alone. For instance, something might be remembered for its combined scale, texture, temperature or sound. In a way, a photograph is too much visual information for me as it’s full of superfluous detail. I am interested in painting what something feels like rather than what it looks like. I would describe my way of using memory as a way of getting to the essence of the subject itself rather than exploring a personal moment. I find that paintings which have a sense of being bigger than their edges retain a certain energy and movement. The arm in Key is curved rather than bent at an elbow as I wanted there to be a strong feeling of a rush and upwards of movement towards the door. The arm and background are similar stripy rainbow colours, which are in a way infecting and affecting one another: neither is distinct because, at that moment, the arm, key, door and environment are closely linked.

You've often said that your colour palette is influenced by your early years growing up in northern California. In some of your works, particularly Self-Consciousness, I'm reminded of San Francisco's enveloping fog, the way it can hover over the city like a diaphanous veil. How is your palette specifically influenced by California and is it still?

I do still feel tied to California. I have been back many times since and sometimes miss everyday Californian life! I lived in Palo Alto, near San Francisco, from when I was one to nine-years-old. I think my colour palette is very influenced by these formative years spent on the west coast: I remember well the beautiful bright sunlight, jewel-like flowers and wide, pale concrete paths. Aside from those environmental qualities, I also hold clear in my mind the Mexican Folk Art you often see in California. My palette, though, is equally influenced by my later years spent in Cambridge, England. I am also very drawn to deeper, more subdued hues, often executed with a controlled tension, which might be described as more European. I like to embrace this range of mood in my work. My very wide palette range means that my colour choices for each painting vary a great deal, often creating a stark contrast between works. I tend to see colour in painting as almost a subject in itself.

I gather you work first in sketch books and then transfer the works onto different size canvases. Do you follow the same process for every painting or does your approach shift from work to work?

I do often work in large sketchbooks filled with different types of coloured paper, using a variety of materials (pastel, charcoal, ink, graphite, acrylic, watercolour). This is where my first ideas are explored and worked through. All aspects of my work exist in these books: simple mark-making exercises; explorations of colour combinations I instinctively like; the creation of abstract forms; figurative images, some of which are from observation. These books are like a visual notebook for me, somewhere for my ideas to live until I feel ready to use an element of them. It is important to say, however, that I do not tend to scale up images directly from the book. It is vital to me that a painting has its own energy, which I feel comes about through the process of intuitive decision making combined with stern appraisal, not knowing what a painting will look like when completed. I use different sized canvases because scale is an important part of a painting’s subject: How we feel in front of a small painting compared to a very large painting is different. With every painting I have a sense of it’s personality and the scale choice is a key aspect of expression. My approach to each work changes in scale, medium, mark and surface. I don’t tend to see my paintings as windows to somewhere else but rather constructions of colour, form and material co-existing to communicate a subject’s image and feeling.

These days, what excites and challenges you most about painting?

The direct connection between eye and hand; seeing an individual’s visual voice.

British Art Show 7: In The Days of the Comet runs from 16 February until 17 April at the Hayward Gallery, London

Text by Tamzin Baker