A new exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery pays tribute to the extraordinary visual provocateur

There are very few people who have so effectively toyed with our relationship to the projected image and the construction of identity than the British collage-artist John Stezaker, whose current review at Whitechapel Gallery is one of the truly great exhibitions of the year. It could be argued that Stezaker has not received the recognition he deserves until rather late in his career, and this show pays timely tribute to the idiosyncratic, and almost violent aesthetic that has made him one of most interesting visual provocateurs of our era. Here, the curator of the show, Daniel Hermann tells us why the artist’s minimal approach to his medium always garners maximum results.

AnOther: Why do you think Stezaker's work is important, and how profound has his influence been on contemporary art?

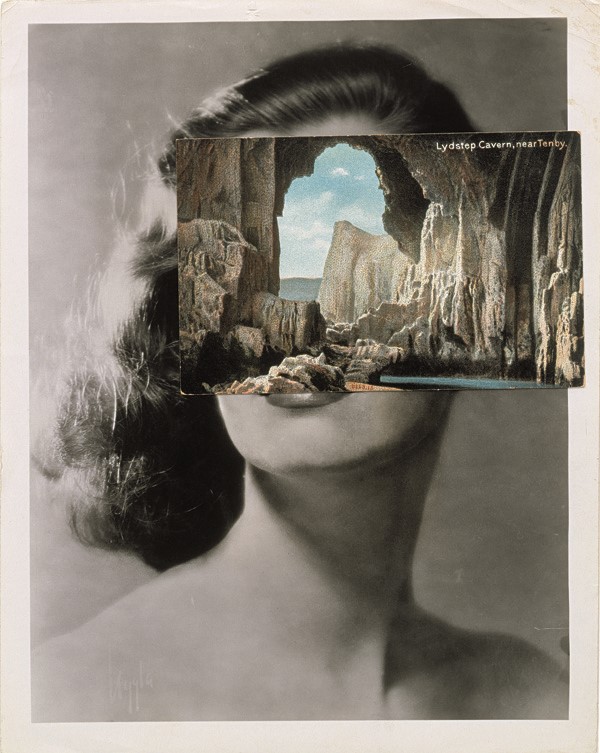

Daniel Hermann: More than anything, John Stezaker’s work is about the act of looking. His works focus on the power of the visual and the fascination of the image. In the past decades, images have become more ubiquitous than ever – we have images on the television, on buses, on our phones and in our homes. This ceaseless and ever-growing flow of images is largely one of function and usage: it serves to sell products, to communicate specific messages or to document particular events. Stezaker was one of the most significant artists to be drawn to the fascination images can exude over viewers, and by minimal intervention he started to isolate them from their original function and allow them to be viewed as works on their own. This re-consideration of the image and the visual as a valid line of artistic inquiry is of great interest to many artists today.

To what degree are some of John's works a comment upon the transience of celebrity, or at least the way in which we perceive such things?

I think ‘perception’ is the key word. Most of the filmstars employed in Stezaker’s works are long forgotten. We don’t perceive any actual likeness to an actual filmstar, but rater an iconographic type. We are remembering our own experience of ‘recognising’ in general, much rather than recognising anyone specific. That’s what makes the works so powerful: the faces are no longer expressive of particular identity, but have become projection surfaces of our own interests, desires and fears. That is infinitely alluring – and frightening.

In what sense did the artist push the medium of collage forward? How did his use of the medium differ from that of his contemporaries?

A lot of collage is very busy. From early Victorian beginnings to Hanna Höch and Kurst Schwitters to Eduardo Paolozzi, collage has often been defined by the quantity of its material. Stezaker is far more economical: his works stick to the law of minimal intervention; rarely using more than two parts. That restraint of the artistic hand is unusual, effective and affecting.

Much of Stezaker's work juxtaposes the male with the female, why do you think that is?

A lot of images represent certain gender roles. Since Stezaker’s work employs historic photographs, the historical distance highlights the artificiality of such roles. A series such as ‘Marriage’ plays with the construction of what we perceive as ‘male’ or ‘female’ and how such roles are staged. I would say the flux of identity is one of his key concerns and I think his work is unsettling because it allows us to bring our own thoughts to it.

Read an interview with John Stezaker in the spring/summer 2011 issue of AnOther Magazine, on sale now. John Stezaker at the Whitechapel Gallery until 18 March. A display of the artist's work is also on display at the Louis Vuitton Maison, 17–18 New Bond Street until 19 March.