Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman are better known for straight documentaries, The Times Of Harvey Milk or Paragraph 147, but when the Ginsberg Foundation approached the duo to make a film about Ginsberg’s totemic beat poem, Howl, it was a far less

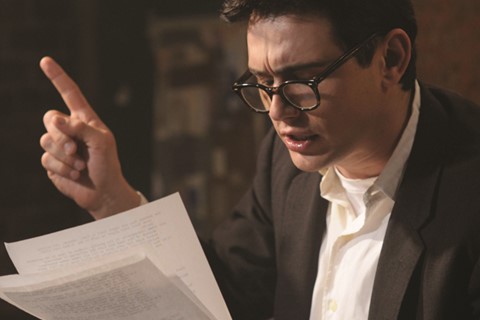

Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman are better known for straight documentaries, The Times Of Harvey Milk or Paragraph 147, but when the Ginsberg Foundation approached the duo to make a film about Allen Ginsberg’s totemic Beat poem, Howl, it was a far less likely treatment of reality that emerged. Using an unusual mixture of story-telling formats, the pair employ a blend of dramatised Ginsberg interviews with enlivened court transcripts from the 1957 landmark obscenity trial, together with a re-enacted incantation of the poem itself by Allen Ginsberg at the famous Six Gallery, in order to tell the tale. As a narrative feature film, Howl certainly pushes experimental boundaries that pull at the moorings of convention, but the real curve ball comes, however, with the injection of graphic novelist, Eric Drooker’s, hypnagogic Beat fantasia. A dazzling illumination of Ginsberg’s “holy vision”, this animated flight of fantasy is possibly the most impressive and a-typical departure for the directors. Epstein and Friedman talk to AnOther about their unusual choices and why it’s important to tell the story of Howl.

You’re documentary makers by trade, how did Howl come about?

Rob Epstein: Originally, we started immersing ourselves in the documentary possibilities of Howl, because that’s our orientation but we didn’t really see a documentary within it. We knew we wanted to make a film about the particular moment in Ginsberg’s life when he came to create the poem, and we wanted Ginsberg and all of his influences to live as their younger selves in the movie, so we knew that we would have to create that world… we just weren’t sure how.

Jeffrey Friedman: Through the course of our research, we found the graphic novelist Eric Drooker. He had collaborated with Ginsberg on a book of illustrated poems called Illuminated Poems and really understood where Ginsberg was coming from. I think he was missing piece of the puzzle for us. It was then that we realised that we wanted to visualise the poem; that we could imagine a trip through the mind of a poet, we could go anywhere.

What were your motivations to make the film?

JF: We certainly wanted to bring the poem to a new generation, you know, to keep it alive, but in the annotated Howl, Allen’s got a little quote about how he was interested in writing Howl in order to create a time bomb that would continue to go off in American cultural consciousness, in case there was a repressive police state or something like that. And we thought, “Okay, it’s time for the time bomb to go off!”

Were you nervous about compromising the essence of the poem through its translation into film?

RE: No, not really. Maybe it was naivety, maybe it was chutzpah, or maybe a bit of both. We likened it to adapting a novel; the novel will always exist in its form and the cinematic interpretation just becomes another interpretation of that novel. It’s just one telling of the story, but it’s using that story as the base.

JE: Everything had to relate to the poem though. Everything in the interview had to feed into the poem and everything in the trial had to feed out of the poem. The poem had be the central character.

How easy was it to gain access to research material for the film?

RE: We did research interviews with Lawrence Ferlinguetti, who published the poem, who still lives in San Francisco (he still has City Lights book shop). And, at the time, Peter Orlovsky, another Beat poet and Allen’s longtime partner, was still living. So all of that informed the movie, but it was the Ginsberg Estate that opened the doors to those people and they also gave us access to a lot of material. Whatever we needed, really.

Counterculture literature of the 1960s is still very much a rite of passage for emergent youth today, why do you think that is?

RE: The smart ones probably understand the historical importance of it, but I think what people continually respond to is the voice of authenticity that it represents and, really, that’s how people encouraged each other at the time: to be as true to themselves as they could possibly be. That’s where they found their own art and their own voice.

Was scriptwriting a new thing for you both?

JF: It was and it wasn’t, because it was all based on transcript. Coming from a documentary background, we’re used to working with existing material and shaping it into a narrative. But you know, this was like taking it to another level.

RE: It’s not unlike what we do with our documentaries, where we transcribe everything that we shoot and then we basically create a script from those transcrpts. Except here we did it in reverse order with this: we created the script first and then we shot that script.

What about the Ginsberg interview in the film, did that actually take place?

RE: That came from multiple interviews that he did over the course of his lifetime. We read a dozen different interviews that he did between 1955 and 1997 and culled from the interviews to create one single interview. It was inspired by a supposed interview that he did for Time Magazine at the time of trial. It’s mentioned in his biographies, but there’s no other evidence of it.

JF: The more that we tell that story, the more I wonder what was going on in that hotel room with that Time Magazine reporter. Did they just get high? [laughs]

You also spent a bit of time at the Sundance Writers’ Lab.

RE: Oh yeah, that was great. Basically, you apply and they select 10 to 12 projects every year and we were lucky enough to be selected. It was kind of a Catch-22 for us though, because right when we got accepted the producers came on board and they were ready to go. They also knew that James Franco had a limited window and they didn’t want us to go to the Lab.

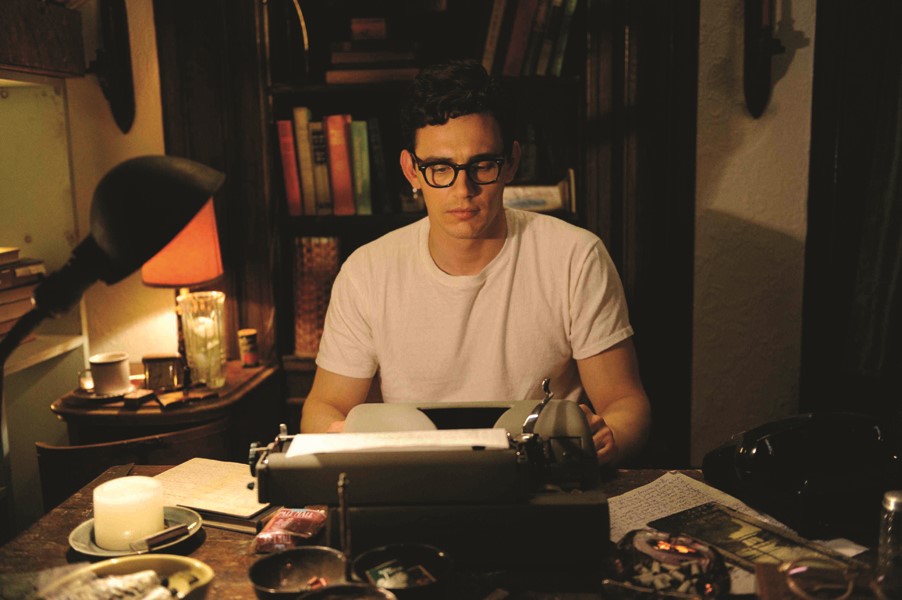

How did you decide on Franco for Ginsberg?

RE: We saw him Pineapple Express and we said “We want him!” [laughs]. “He can play Allen Ginsberg!”

JF: No, he came to us through our Gus [Van Sant] and it just felt like a natural fit. We found out that he was a poet and a student of literature and that he’d been a fan of The Beats since he was 14. He was really excited about the idea. It required some real acting and some real thinking; it was a lot research and a lot of emotional work for him.

Would you agree that Howl potentially testifies to how little has changed, as well as how much has changed?

JF: The obscenity trial certainly reminds me of how little has changed. The trials that we have today could practically be the same trial: what is permissible speech; what is the role of an artist; should there be limits to artistic expression; can sexuality be obscene? Those are all things are still issues. Allen’s talking about corporate mind control through media advertising and controlling the population through mind control. This is where we are now. They were just figuring out how to do it back then.

Howl is released in UK cinemas on 25 February.

Text by Melissa Osborne