It’s long been considered a classic, but the film’s production was a horror story all of its own, a new book reveals

In 1968, film director Roman Polanski brought Rosemary’s Baby to life and forever changed the way we imagine horror films. In a genre best known for its gruesome and grisly tropes, Rosemary’s Baby made the realm of the supernatural all too plausible in a delectable mixture of the mystical and the mundane.

The exquisitely cinematic film, which moves at a dreamlike pace, takes place inside New York’s stately Dakota building on 72nd Street and Central Park South, where a coven of witches decides to impregnate a young Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow) with the child of Satan. Rosemary’s Baby is meticulously crafted so that every moment slowly unfolds in an exquisite tension that denies release until a denouement so quiet you realise there is no escape.

Yet, despite – or perhaps because of – the aesthetic perfection of Polanski’s work, the film production was a horror story all its own, one that is meticulously recounted in This Is No Dream: Making Rosemary’s Baby by James Munn (Reel Art Press). Set for release on June 12, the 50th anniversary of the legendary film, the book takes behind the scenes and on to the set, where drama was ever present.

“There was never a dull moment,” set photographer Bob Willoughby observes, as his photos help to convey the dark undercurrents at work. Although Polanski was riding high, at the height of his stardom while making this film, his countless scheduling delays put his job in jeopardy. At the same time, actor John Cassavetes, who co-starred as Guy Woodhouse, was ready to fight Polanski over creative differences.

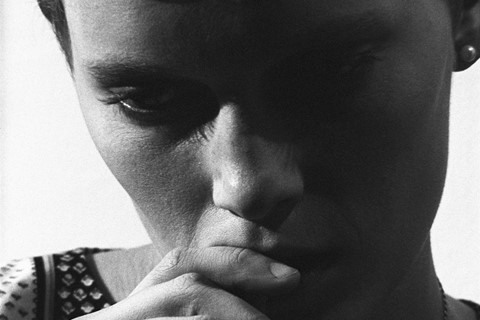

Farrow’s then-husband, Frank Sinatra, cared nothing for her work, and threatened to leave unless she abandoned her career to become a full-time wife. Farrow did no such thing; she dug her heels in for her craft, going so far as to eat raw liver in a scene even though she was a staunch vegetarian. The off-screen stress added to the harrowing intensity of the film, creating a sensation of agitation and strain that is seemingly everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Munn captures all of the drama and spectacle in his vivid prose, while Willoughby’s photographs bring this kaleidoscopic crew of characters to life.

“Bob Willoughby remembered a day during filming when Farrow was particularly happy: ‘Mia was seeing Frank Sinatra during the filming ... He had taken her to lunch this day, and had wined and dined her and Mia returned to the set full of the joys. She was like a giggling school girl, tipping over the assistant director’s chair, climbing on top of the wardrobe. She was a panic, and of course I was clicking away. As she was being bundled off to her dressing room, she leaned in to me, giving me a most memorable parting line: ‘Older men always try to spoil me!’

‘There are 127 varieties of nuts,’ Polanski once said in an interview. ‘Mia’s 116 of them.’ Farrow, by Polanski’s view, was ‘heavily into the whole range of crackpot folklore that flourished in the 1960s, from UFOs through astrology to extrasensory perception.’ Said Farrow, ‘The sixties were in full bloom. Roman was humming, “If you’re going to San Francisco, be sure to wear some flowers in your hair,” and I painted the walls of my dressing room with rainbows, flowers and butterflies.’ Added to that were dragonflies, birds, a sunburst, a large heart, the words ‘peace,’ ‘love,’ ‘live’ and a color scheme of purples, reds, yellows and greens. Farrow quipped about entering it for competition at the Los Angeles Museum of Art, if only she could move it.

‘They gave me a ping pong table because I was a kid, and I was getting no exercise,’ Farrow said. ‘I wouldn’t even see the light of day. One night I even slept on the set.’ Countless and sometimes fiercely competitive games ensued involving Farrow, Polanski, the Sylberts Anthea and Richard, various crew members and even Cassavetes’s Dirty Dozen co-star Jim Brown, who was visiting the set. But it was Cassavetes who dominated many of the matches. Only Hawk Koch could best him. ‘I beat John Cassavetes for a lot of money,’ recalled Koch.

During lulls in the filming, the energetic director practiced quick draws with a prop six-shooter and, at the end of the shoot, the crew bestowed upon him a real one with his name inscribed on the ivory handle. ‘He’d have his six guns out and he had a cowboy there that was a six gun draw expert who was one of the best in Hollywood,’ said actor Craig Littler. ‘So he’s teaching, and Roman would be sitting there—he’s a little bitty guy—and I’m sitting there, as a young actor looking at all of this, going, “So this is moviemaking, huh? This is, this is the big time?”’

This is No Dream: Making Rosemary’s Baby by James Munn is out now, published by Reel Art Press.