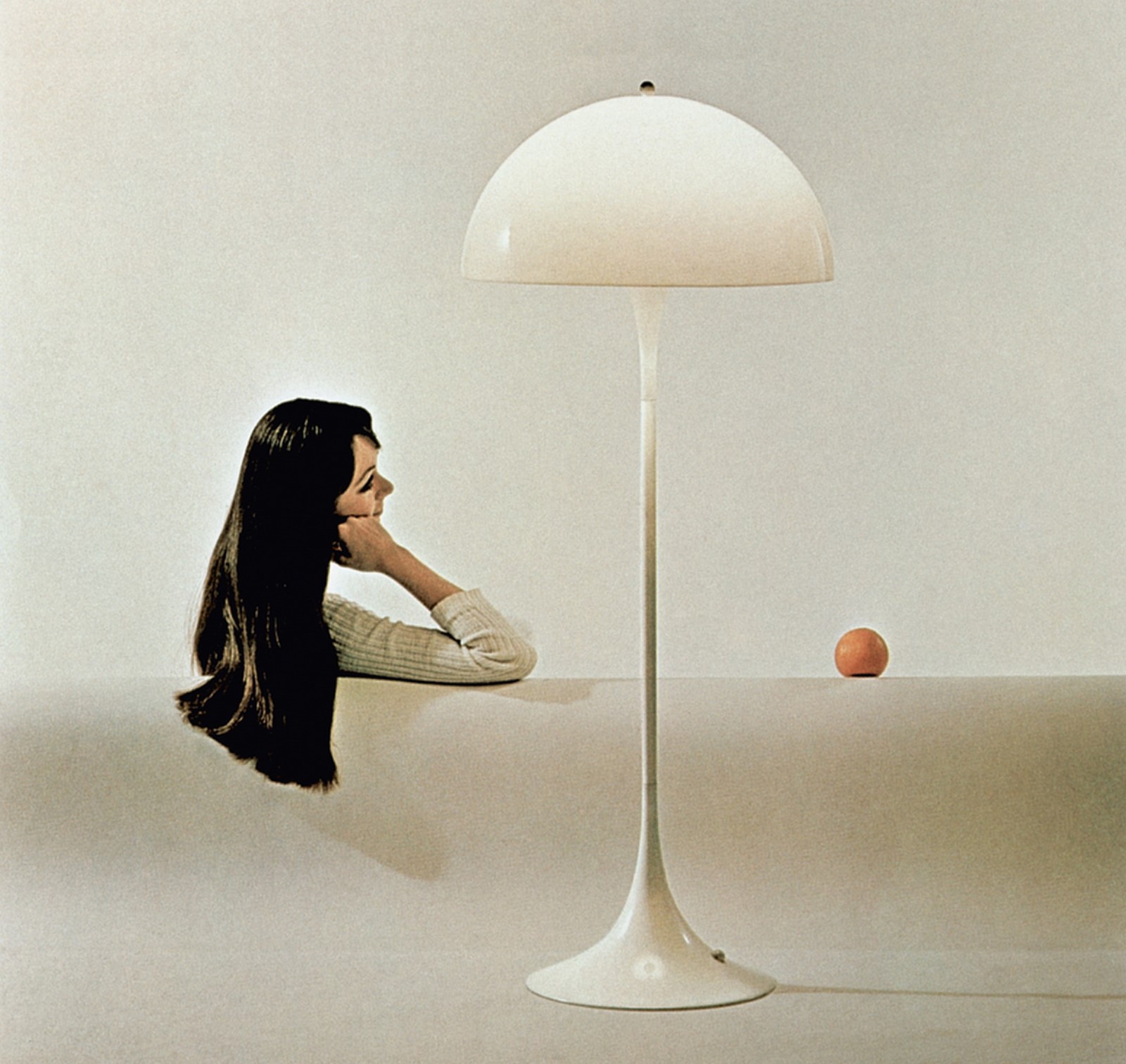

The irony of being celebrated as an icon of contemporary design would not be lost on Verner Panton. Two decades have passed since the Danish designer’s death, but as we dive head-first into a world of political and economic unrest, the desire to break social convention that defined his work in the 1960s and 70s is as enticing now as it was then. Considered the enfant terrible of his generation, Panton embraced what it meant to be a Danish designer while redefining the function of furniture.

Coming of age in a post-war economy, Panton was familiar with the habits and needs of the ordinary person. Intelligent design, to him, should not be reserved for the wealthy, but made accessible to the mass market. The revolutionary designer blossomed as part of a movement that believed in widespread social progress through sophisticated design solutions and reforms which ultimately paved the way for social welfare models that continue to create global change. He was a maverick and an outlaw, yet his work is now synonymous with the unprecedented shift of an entire industry. Panton famously said, “A less successful experiment is preferable to a beautiful platitude”. While resilient and progressive, the world he set about building with his dedication to pragmatic design was not without its challenges, but it was a world that promised social mobility and an optimistic future.

As some of his most recognisable works, Panton’s truly radical concepts were his environments, the most famous being 1970’s Visiona 2. Defining the signature curves and colours of the era, these “social uteruses” were a figurative interpretation of an idea belonging to art theorist Bazon Brock. Visiona 2, the designer’s contribution to an international movement channelling the innovation of post-war technologies and systems as environments for modern life, sits elegantly alongside architectural projects Archigram in England and Archizoom Associati in Italy. The difference between Panton and his architectural contemporaries was his approach to change. While many collectives focused on the wider environments and societal changes, Panton maintained a focus on the behaviour of individuals, perhaps hoping that by altering one individual’s experience of design he could spark a domino effect.

Panton is often compared to function-led designer Dieter Rams. The two have had similarly profound impacts on the world of design – Rams’ principles of “good design” have famously shaped the work of Apple designer Jony Ive – and while many were quick to condemn Panton as a clown or, at best, a fantasist, it is with the benefit of hindsight that we can see the appeal of both approaches. Rams was efficient, effective and restrained in his approach, while Panton sought out emotional experiences and challenged us to feel something in our environments. Referred to as neo-avant-gardism, Panton’s highly expressive designs are a product of an industry set free. During the first and second world wars, materials and manufacture were defined by military needs and a basic commitment to survival. While this limited the production and design development of furniture, it did inspire innovation and, when the dust settled, designers like Panton were faced with a brave new world of opportunity.

Arguably one of the most iconic chair designs of all time, the arrival of the S chair (often referred to simply as the Panton chair) in 1967 firmly established the designer as a true innovator. This groundbreaking seat, while elegantly simple in design, was the first time any designer had successfully manufactured a chair that could be moulded from a single piece of plastic. When the S chair was presented to the public and press at Cologne’s famously influential furniture fair it became an instant sensation but the design, in prototype form, had in fact existed since 1962, and the five-year journey to reach a point of mass manufacture was one of great political manoeuvre.

In the early 1960s, Panton was attempting to create the sinuous form in plywood, but his efforts were swiftly refocused on designing a curved chair in plastic. This would not have been possible had the designer not collaborated with Danish plastics manufacturer Dansk Akrylteknik, which helped to fabricate a prototype in 1962. Within the same year, Panton moved to Cannes in search of a European producer, but it was in Basel that he found Willi Fehlbaum, a manufacturer finally willing to take on the risk. Fehlbaum decided that his own company, Vitra, would invest in the chair. Soon after making this arrangement, Panton left Cannes to relocate to Basel, partly to assist Fehlbaum in the painstaking development of this revolutionary product. It wasn’t until 1971 that the ideal material had been found for the chair: thermoplastic polystyrene, also known as ‘Luran S’, produced by the chemical company Bayer, who were familiar with Panton’s work having helped him realise the Visiona exhibitions.

While the S chair is just one of Panton’s extraordinary designs, the conversation surrounding it exemplifies the somewhat confrontational relationship the Danish icon maintained with his industry throughout his career. Many have speculated on the true inspiration behind the chair. Some designers of his day believed he stole the idea from them, and was simply a copy-cat, whereas others argue, as stated in Phaidon’s newly published book Verner Panton, that the chair is the “ultimate demonstrative expression of Panton’s impatience with the handed-down tradition as well as an attempt to outperform, once and for all, the sculptural-artistic tradition of Danish applied art at its home ground”.

One thing that is unflinchingly evident in Panton’s work, from the S chair to Visiona, is that he believed in the choice of the everyday individual. Through careful study and application of pattern, systems and colour Panton created mass-produced products that could be curated by the end-user to build their own unique world, inspired by his.

Verner Panton, by Ida Engholm and Anders Michelsen, is out now, published by Phaidon.