On Alfred Hitchcock's birthday, we select our favourite Modernist masterpieces on the silver screen – starting with North by Northwest's Vandamm House

Alfred Hitchcock was a master of many things – suspense, innovative camera work, technical effects, sly cameos. But it's his inimitable aesthetic that demonstrates his true artistry. He meticulously plotted out his films down to the finest detail, and was a great admirer of beauty, frequently casting Hollywood's most mesmerising women and creating sumptuous spaces for his characters to inhabit. The most memorable of these, in our opinion, is the breathtaking Vandamm house, home to the terrifying villain of North by Northwest, and the perfect example of Modernist architecture's powerful impact as a cinematic setting. Here, in honour of what would have been Hitchcock's 116th birthday, we take a closer look at the Vandamm masterpiece alongside our most-loved Modernist moments on film.

The Vandamm House – North by Northwest

When Hitchcock read Ernest Lehman's screenplay for North by Northwest, he envisioned his baddie, the sinister Phillip Vandamm, as the master of a splendid Frank Lloyd Wright house atop Mount Rushmore. This idea posed two key problems: Frank Lloyd Wright was the most in-demand Modernist architect in the world and a bespoke house for the film would have been utterly unaffordable, and the granite cliff face was far too fragile to build on. But the director was undeterred and commissioned designer Gutzon Borglum to create a ranch house, in Wright's signature style, on a Hollywood set.

The "limestone" exterior was in fact a matte painting (a pre-digital effect used to combine a real set or location with a painted construction) and the interiors – complete with covetable hardwood flooring – were built on a soundstage. As writer Sandy McLendon explains, "The interiors were masterpieces of deception: nearly nothing was what it appeared. The limestone walls were mostly plaster, real limestone was used in a few places where the camera would be very close. The expanses of window were mostly without glass; glass reflects camera crews and lights." All scenes involving the house were shot at night so that the effects would look more realistic, and the results are mind blowingly convincing to the degree that many people still believe the house to be a first degree piece of Wright architecture.

The Sheats Goldstein Residence – The Big Lebowksi

The iconic setting for the Dude's memorable encounter with porn king Jackie Treehorn in The Big Lebowski, the Sheats Goldstein Residence is the handiwork of legendary American architect John Lautner. Built for artist/doctor duo Helen and Paul Sheats between 1961 and 1963, the house is a harmonious medley of concrete, wood and steel designed to interact with its hillside setting. Lautner conceived every element of the house, including the complementary furishings, and was given free reign to update it in 1972 when businessman James Goldstein bought the property in a state of some disrepair and turned to the architect for help. Now a Koi fish pond runs under the living room, and the doors and windows are motorised and can vanish at the touch of button.

When the Coen brothers' location manager Robert Graf came across the house in his search for Treehorn's abode, he was smitten, his imagination captured by the 750 drinking glass skylights that punctuate the concrete coffers in the living room and its tan coloured leather couches that conjure up visions of swinger parties past. "There were a couple of other houses we liked on the beach, but we kept coming back to the Launtner house," he recalls. And we're very glad they did.

The Villa Necchi Campiglio – I am Love

It's not just Tilda Swinton's Emma Recchi that beguiles in Luca Guadagnino's brilliant film, I am Love – the starkly beautiful house that she and her family inhabit is equally unforgettable. A wonderfully accomplished example of Italian architecture of the inter-war period, the Villa Necchi Campiglio was built by Milanese architect Piero Portaluppi between 1932 and 1935, with later renovations by Tommaso Buzzi. A melodic synthesis of architecture and decorative arts, the house represented a new idea of luxury typical of the period, favouring technological innovation and fine materials over classicism. And it was this that caught Guadagnino's attention. "I wrote a script that called for a cube of marble with a big staircase and sharp surfaces," he told Port Magazine. "I was banging my head trying to find a home that suggested great wealth but also a restrained sensibility."

He saw the villa in a book some years later and immediately resolved to shoot there. "It shows the obsession with perfection and details that the Milanese bourgeoisie have. Old money always comes with great charm. Their real success is making others believe that money doesn't exist – and luxury, as most people perceive it, doesn't really exist in this house. It's very severe, and feels almost unmoveable, like a piece of rock."

Googie Diner – Pulp Fiction

The dreamy diner in which Quentin Tarantino shot the intro and outro to his 1994 cult classic Pulp Fiction is another marvellous Modernist moment on film, albeit a less extravagant one. The restaurant – complete with pastel-tiled detailing, sweeping wooden benches with red leather cushions and enormous windows – was situated on Hawthorne Boulevard, south of Los Angeles airport and originally opened in 1956 under the name Holly's (it was later changed to The Hawthorne Grill). By the time Tarantino decided to shoot there it had been closed for four years but after the success of the film, local resident Chris Garnreiter reopened the grill in 1995. Alas, he went bankrupt a year later and the building was demolished in 1999. Happily it remains immortailsed in one of the most iconic scenes in film history.

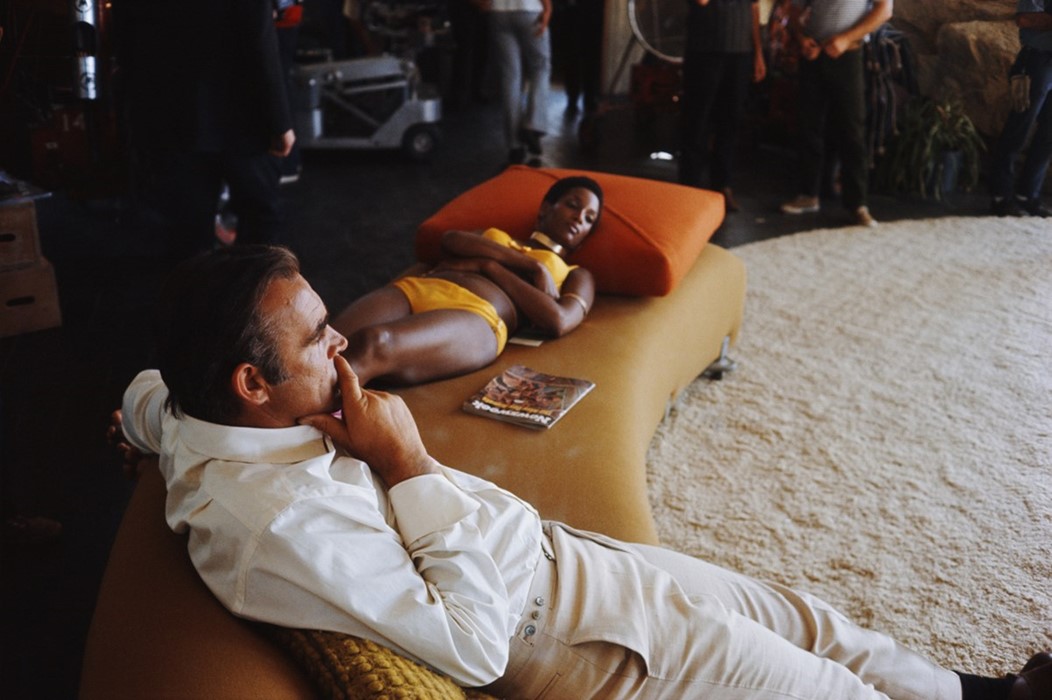

Elrod House – Diamonds are Forever

John Lautner was behind another of our favourite film dwellings – the Elrod House in Palm Springs, which stars as Willard Whyte's winter retreat in Diamonds Are Forever. Much like the Sheats Goldstein residence, the building is designed to complement and incorporate its natural surroundings – the exposed rock of the desert floor encroaches into the living space to dramatic effect. The vast domed roof is designed to shade the house from the strong desert sun and is divided into raised sections to accomodate skylights for an indirect light source. James Bond production designer Ken Adam was looking for exotic Palm Springs locations to house the film's villain and was delighted when he came across the building. "It was absolutely right for the film," he recalls. "It was a reinforced concrete structure, very modern and fabulous. I said, 'It's as though I designed it. I don't have to do anything!'"