The lauded director discusses his latest film, Carol, and the photographer who inspired its sumptuous shots

Patricia Highsmith first published the groundbreaking lesbian romance The Price of Salt in 1952 under the pseudonym Claire Morgan. The tale of an affair between a tremulous young store clerk and a worldly housewife in 50s New York was a departure from Highsmith's previous work and its starting point stemmed from personal experience. At the age of 27, in need of money to pay for therapy, Highsmith was working as a sales clerk in a department store in the run up to Christmas when she glimpsed a glamorous blonde in a mink coat among the fevered shoppers. This scene is beautifully brought to life in Todd Haynes' captivating new film of the book, Carol. Starring Cate Blanchett as the titular Carol and Rooney Mara as Therese, the film crackles with erotic tension. Carol is an unhappy New Jersey châtelaine about to divorce her husband; Therese is a gamine in a santa hat who excites the older woman's senses.

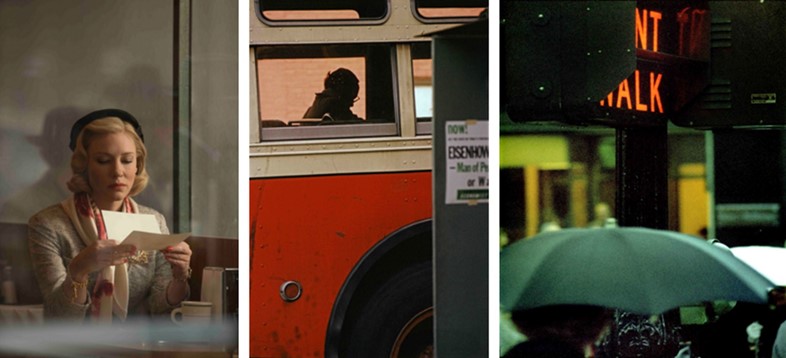

This is the second 50s-set film Haynes has directed but where 2002's swooning Far From Heaven was inspired by the lush melodramas of Douglas Sirk, the visual language of Carol is grittier, spiced with threat and mediated through windows, mirrors, and camera lenses, in an homage to the New York photographer Saul Leiter. Haynes, who launched his career with a biopic of Karen Carpenter enacted by Barbie dolls, came to prominence in the early 90s as part of the New Queer Cinema movement and is known for intelligent films that are usually focused on female characters. Indeed, he has worked with the top tier of Hollywood actresses, from Julianne Moore to Kate Winslet and Blanchett, who memorably played Bob Dylan in his omnibus biopic I'm Not There. Here, on the eve of Carol's release, he discusses his creative process, working with Blanchett and Mara, and the female photographers of the 50s who inspired him, along with Leiter.

On Patricia Highsmith...

"I'd read a bit of Patricia Highsmith before that but not a lot. As I read a bunch more Highsmith after The Price of Salt, I saw it's sort of unique but I really did see a continuum in her work that made me even more impressed with the way she handled a story about love and how unsentimental the novel is – how clear-eyed and almost tough it is. Her work has always been great for film, which loves to tell crime stories and illicit situations. She creates a sense that anybody could stumble into these circumstances, they're very relatable. The mental workings of the subjects are immediately identifiable as human; they're discomfiting and they're fascinating and you can't stop reading. You find yourself in the actions of the characters."

On Nabokov...

"One of the published versions of the novel, maybe when it came out as Carol in the 80s under Patricia Highsmith's name officially for the first time, features a quote – and I've been meaning to track this down but I haven't had the scholarly time to do so – which says it inspired Nabokov. Maybe he read it and maybe he said something about it at some point and it was extrapolated from that. Obviously the age difference is a major factor in Carol and it contributes to the lesbian challenges of being two women in the world at that time. It's certainly a major challenge in and of itself."

On how falling in love makes you an outlaw...

"I always love it when something extremely universal and human is described for all of its illicit aspects and the ways in which the mental processes get excited to such a degree that you are an active and incessant and obsessive producer of narratives in your mind. You're stewing and brewing with possible stories and outcomes. You're thrust out of society, in a way, you don't feel like you can relate to normal, banal situations, they have no relevance to you whatsoever. Your actions and your desires exclude you and in a sense elevate you to something completely your own, in your own world. But you are also completely and totally powerless to your fate, which in the lover's case is, well, do they love me back? And in a criminal's case, is will I get caught? You're helpless but there's a weird pleasure. The isolation produces all of this stimulus."

On the photographs of Saul Leiter...

"In Carol, we definitely keep returning to the predicament of looking as a visual strategy in how the film is put together. It was very conscious, as something that puts the subject on one side of the glass and the object on the other and filters their access to each. I think that visual language is a way of just revealing the act of looking as a predicament to begin with and one that is never completely easy to achieve. There's always something in the way of what you want. [Saul Leiter] is a clear influence because he loved to do that and he did it so beautifully, disrupting his subject matter and finding planes of intersection and abstraction in his colour photography. While at times you think you're looking at an abstract painting, it actually gives such a specific sense of time and place because of the kind of light and how it plays on glass and how it interferes with dust and dirt and grime. The real conditions of being in that city at that moment are revealed as palpable and beautiful and elemental in a way."

On Leiter's female contemporaries...

"[There are] these female photographers who we discovered in the research as well, who were working in the colour medium at the time. Esther Bubley, Ellen Levitt, and Ruth Orkin are three key women photographers from the period. Ruth Orkin is really interesting because she also collaborated with her husband Morris Engel on docudramas. The films that they made were in were black and white, but they were shot in real places, on location, with real actors and real natural light and all the background noise of a real New York City and so they were really useful documents for our research. The best known one is Little Fugitive, about a little boy who runs off to Coney Island for the day, but Lovers and Lollipops was the one that we watched the most because it had a woman at the centre of the story and it had locations that were more relevant to Carol, including the doll floor of Macy's department store. It looked like a war zone, Macy's toy floor – just how messy and crazy and dirty and un-fancy and un-glossy New York City in the early 50s really was. These women photographers were sort of a revelation given that Therese in the story is an aspiring photo journalist herself."

On working with Blanchett and Mara...

"When I came on board, we needed to cast Therese so that was one of my big tasks. But Rooney's work had made it easy for me to do that. She holds up, man. She's so serious, she's so smart, she's so prepared – she's very similar to Cate. They approach their work with a similar quiet intensity and preparation and professionalism and yet they're both incredibly kind on set and incredibly easy to be around and lovely to share the days with. I had heard that about Rooney already; I talked to directors who had worked with her already and they just said it was such a pleasure. She doesn't really play the Hollywood promoting game like other actors do."

On New Queer Cinema, Chantal Akerman, and resisting labels...

"The mantle of the New Queer Cinema that I and my earlier films were associated with was so specific to that time and place and to a really unique set of circumstances which had everything to do with the AIDS crisis and which created a kind of artificial urgency – a serious need for speaking out at all levels and in various kinds of ways, including artistically, about what was going on. So that produced not only invested and committed and driven artists making work but audiences that shared the same interests and wanted to kind of take on the status quo.

These days, the identity politics moment, particularly in the United States, has reached a kind of frustrating extreme that I just sort of thought we'd moved past. I think the resistance that [fellow filmmaker Chantal Akerman felt] against naming and categorising is one that I feel around identity politics in general and I totally understand it. But she did understand and explore the lives of women and the sadness of women in film, with her own body sometimes at the centre of that in ways that I do think is important to name. Maybe that's not something she had to do at all but we can do it – while realising that she was doing so much more in the process."

Carol is in cinemas from November 27. The exhibition Through a Lens: Saul Leiter and Carol is at Somerset House until January 10, 2016.