James Hyman, the man behind the biggest magazine collection in the world, is not so much a hoarder as an avid collector of pop culture. His love of printed ephemera began in his teens, when he would hungrily consume new issues of magazines and records to source information for his role as a scriptwriter for MTV. “There was no internet back then, obviously, not until around 1995,” Hyman explains, “so I would collect magazines like The Face and Rolling Stone to come up with facts for the presenters to use when hosting playlists. Stuff like: ‘coming up now is Madonna! She’s currently on tour in Italy, and her most recent video was directed by Jean-Baptiste Mondino.’ That kind of thing.”

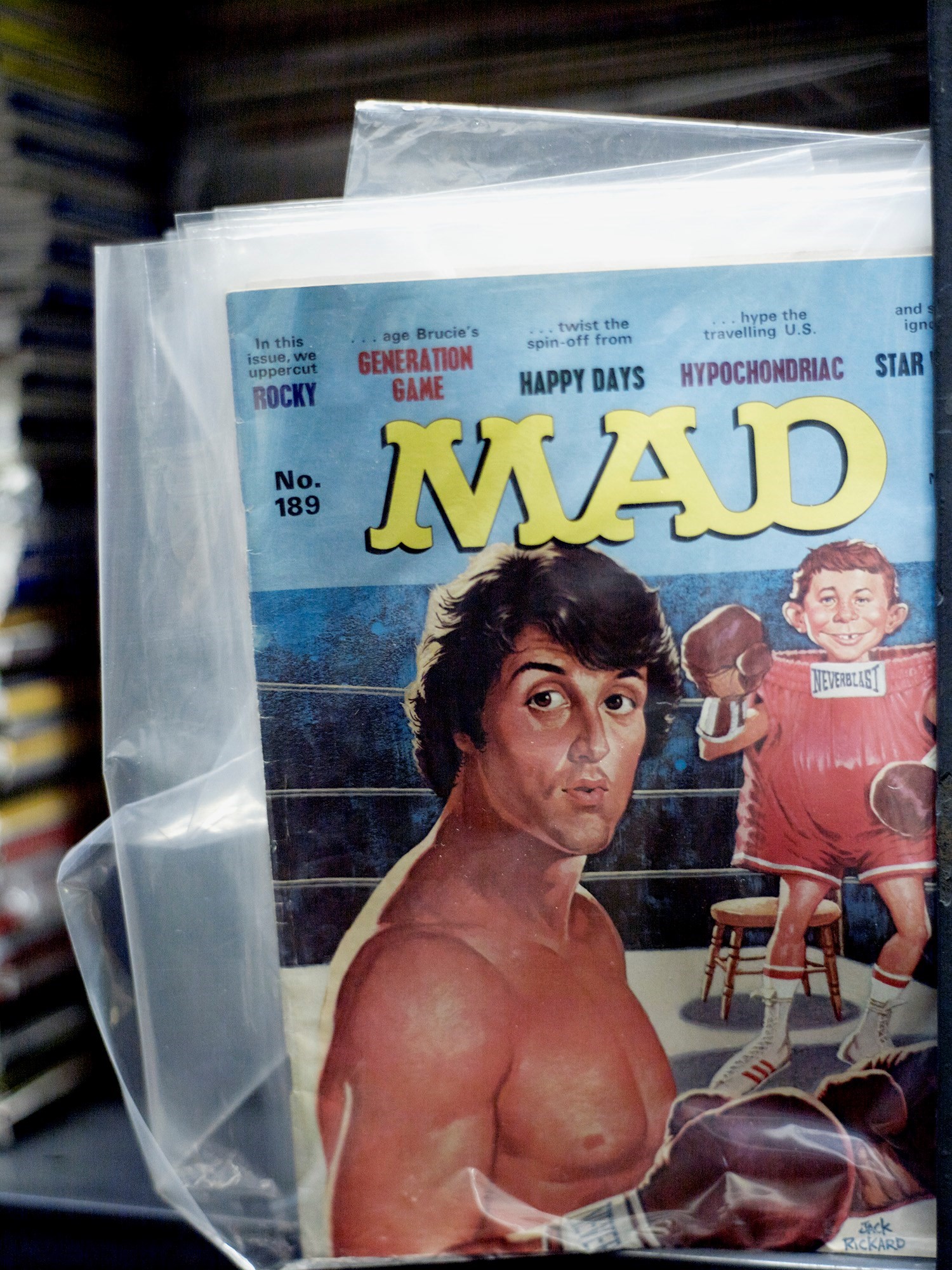

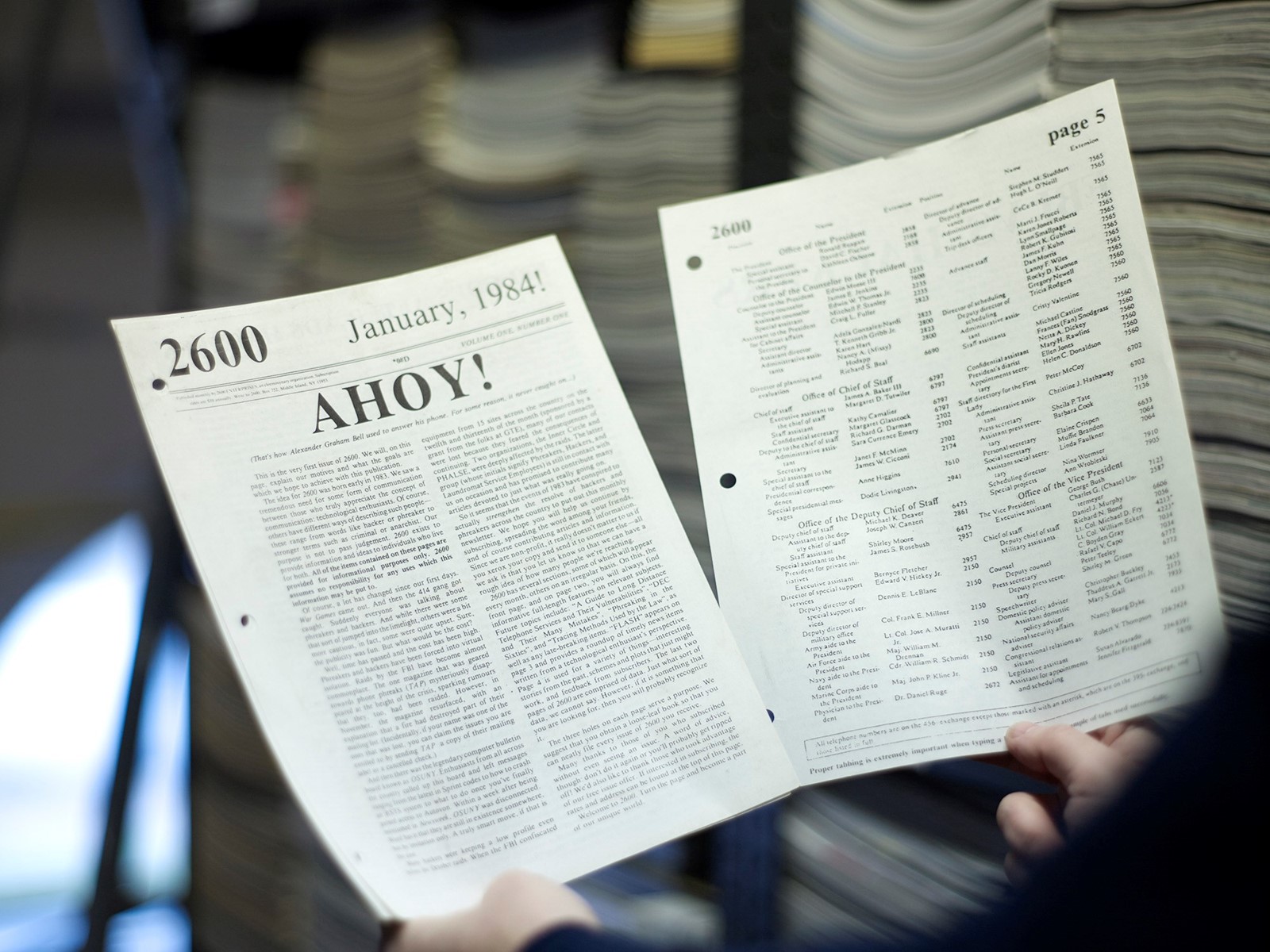

25 years on, the collection, which used to fit on a solitary bookshelf in his childhood home, encompasses 3,000 titles, 80,000 individual issues, and spans over a century of publishing history. More than half of the titles included in it can’t be found in the British Library. In short, collecting doesn’t come much more dedicated, or conscientious, than this.

As the collection outgrew both his spare bedroom and the storage he had outsourced, Hyman decided to move it to a warehouse space near the banks of the Thames, in south London. It’s in this space, and primarily from the comfort of an armchair nicknamed ‘the throne’, that exhibition curator and archivist Tory Turk is reorganising it in alphabetical and chronological order, with the intention of digitising the whole thing – 70,000 items, currently, and forever growing – in the near future. When AnOther stops by to speak to the pair, she is literally in the middle of the letter ‘R’ – stacks of titles from the Radio Times to Rave Magazine are piled high all around her. It’s something to behold, drumming home the enormity of the task at hand. “What’s amazing is that this whole thing has just come from one guy who really loved magazines,” Turk tells, leading us down rows of shelving that is buckling under the weight of so many pages. “He was dedicated to them. This is his bedroom, effectively, but 25 years later.”

The archive’s startling comprehensiveness is almost entirely due to this dedication. “I used to get real anxiety about missing issues,” Hyman adds. “When I went away on holiday I’d be like, ‘shit, am I going to miss that?’ I’d have the newsagents save them for me. When multiple covers started coming out, that really caused some problems – I think Dazed was one of the first to do those.”

Some of the most precious titles in the collection are the least expected. Cult zines Factsheet Five and Cheap Date are up there, as is Faerie Magazine. “I can’t remember the tagline for Faerie, but it was for people who are enchanted by the forest. It had Little Red Riding Hood shoots, and wolves, but it was glossy, it was beautiful.” Elsewhere, a 1947 issue of the New Musical Express, from before it was even known as such, is laid out carefully on a bed of tissue paper, in pride of place. “The old NMEs took me about a week to sort though,” James confesses. “The layouts, and design, and graphics, and illustration… You just kind of get distracted.” The ‘letters pages’ of old publications present an extra special source of treasure – many music and arts journalists reach out to Hyman in a bid to source their first submitted notes in favourite publications. “Morrissey’s first letter was in an NME,” Hyman tells me. “He was 14 years old, and it was published, along with his address. Imagine!”

In time, the archive will be available online via a subscription service, but Hyman is emphatic that his last concern is making money from it. “It’s about a cultural legacy,” he explains. As such, it will be carefully indexed and correctly credited, rivalling the online search engines we’ve come to rely on, and which, all too often, seem to breed imprecision and incomplete research. “Like Google, for example – it makes you think it is giving you everything you want, but because we have so much here that isn’t on there, we realise how much is missing from Google. You know? It gives you the illusion that what you’ve got is good enough. And it is good, but it can be far, far better.”

Does living and dealing so closely with the past make him nostalgic? “I don’t want to live in the past, but I do think it’s important to shape the future,” Hyman replies. “They say that if you don’t learn from history, it will just repeat itself, and you can apply that to pop culture, too.”

With special thanks to James Hyman and Tory Turk.