From Superstudio's famous square to the genre-defying cactus chair, we pinpoint the pieces that defied convention and came to embody Postmodernism

The inaugural exhibition at Vitra Campus’ newly opened Schaudepot shows a collection of key works of Radical Design, the movement that defined Italian design in the 1960s. In its heyday, the movement generated manifestos, unconventional design vocabulary, trans-disciplinary methods and utopian ideals, while its followers argued for active and critical engagement, and worked determinedly against the establishment.

Likewise, the furniture that emerged from Radical Design critiqued both consumer society and the status of women, as well as challenging the status quo for materials – using foam, latex and occasionally flames to blow perceived boundaries. Heng Zhi, the show’s curator, says: “The pieces have a strong visual impact, but to me, it’s their socio-political critique that defines them. These objects show how designers can engage with problematic issues and elite culture. They also capture the changing domestic space, which was adapting to new technologies and bringing in elements of nature”.

The critical awareness implicit to the movement has continued to influence the work of designers and artists alike: odes to Radical Design, and movements such as Critical, Social and Participatory Design, continue to thrive. Here we commemorate five key moments from both the movement and the exhibition paying tribute to it.

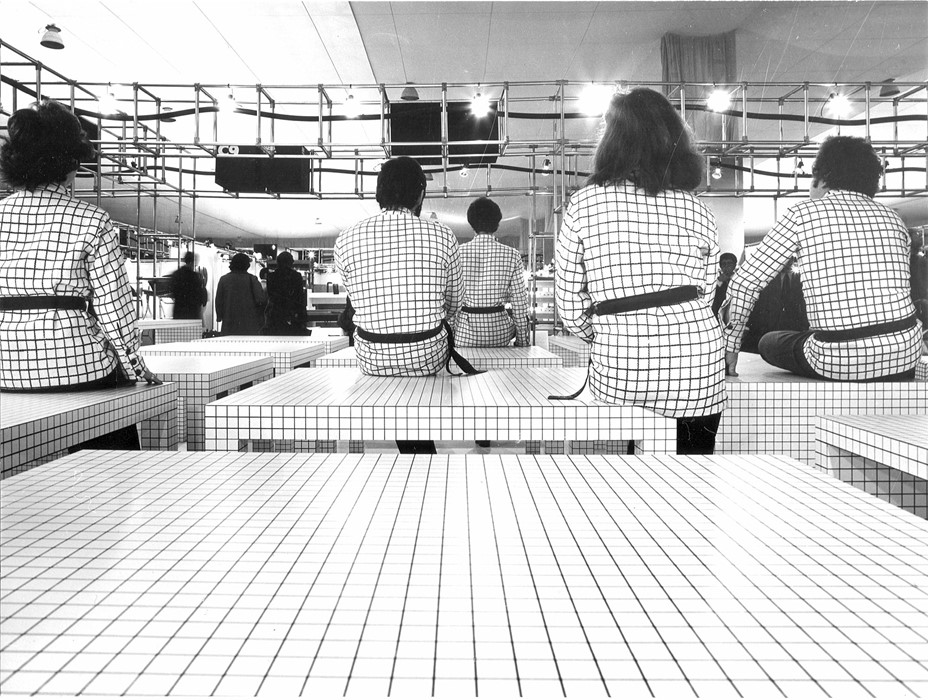

Quaderna, by Superstudio (above)

Superstudio, an architectural studio founded in Florence in 1966, designed their Quaderna range with the square pattern synonymous with their practice – it covered everything from their furniture and architectural plans to collages and films. The square pattern was a symbol of the studio's utopian ideals and an expression of their desire to overturn tradition. By establishing a sort-of 'Supersurface', Superstudio carried the rational views of modernism to their extreme – laying out their absurdities and carving out the role for the postmodern in furniture, and in everyday life.

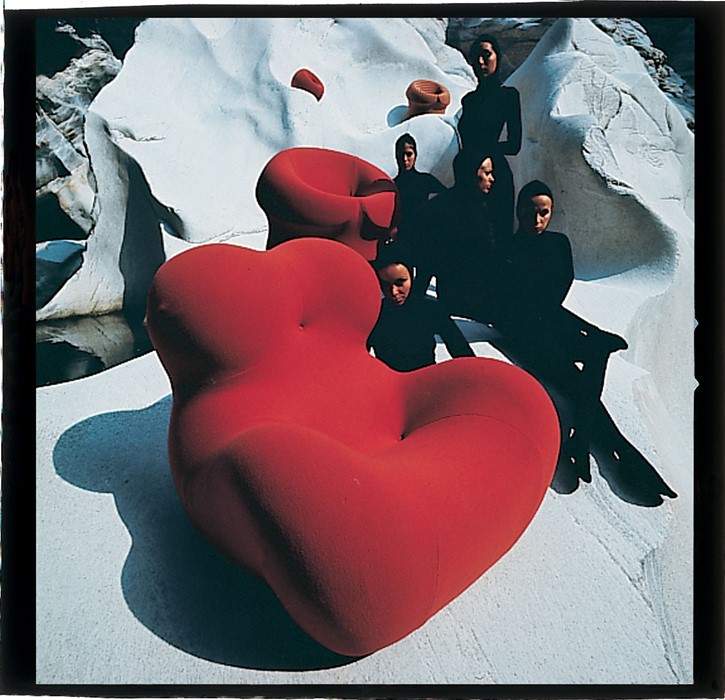

Donna, by Gaetano Pesce

Italian industrial designer Gaetano Pesce’s furniture had long been concerned with mirroring anthropomorphic shapes, and for the Donna chair, he based his design on prehistoric female fertility figures. Aesthetically, the chair has a ball attached, a sort of footrest that, according to Pesce, symbolises the prejudice and oppression that he saw to be holding women captive in the 1960s.

It was unconventional in its manufacture, too – the chair was made from a dense, foam rubber that was revolutionary at the time. It could stand without any supporting structure and be vacuum-packed and stored at around 10% of its size. This allowed customers to transport the piece with ease, and watch their chair re-inflate as it popped out of the box.

Lassù, by Alessandro Mendini

In 1974 Alessandro Mendini, a journalist, architect, artist and designer, set two identical chairs on fire outside the office of Casabella, the magazine he was then editing. One was burned almost to the ground, the second bore only superficial traces. The burning of the chairs was heavy with ritual symbolism, Mendini’s intention being to, quite literally set the chairs within the context of life and death – as he described, “mini-monuments for spiritual use”.

The chair also challenged what was plausible for a functional object; as well as being set on fire, the Lassù was built at miniature scale atop a pyramid structure. As with much of Postmodern design, functionality wasn’t the focus, it was the Lassù’s role in its own mediation (via the cover of Mendini’s magazine).

Cactus, by Guido Drocco & Franco Mello

Guido Drocco and Franco Mello designed their Cactus with the intention of blurring the lines between the indoor and outdoor. Their “hall-tree”, made from polyurethane foam, is equal parts sculpture and coat-rack. An ironic totem, it played a great role in Radical Design’s revolution of the domestic landscape, and set a tone of humour and ambiguity that continues to this day. The Cactus has been reproduced in collaborations with designers such as Paul Smith and the magazine ToiletPaper.

Capitello, by Studio 65

Inspired by a photograph of the Acropolis in Athens in which exhausted tourists were resting against truncated columns, in their Capitello chair Studio 65 deconstructed and quite literally overturned the Corinthian column. Their seat transforms both the function and symbolism of the column, taking it from the elites and giving it – in the form of pliable polyurethane foam – to the masses. Franco Audrito and Piero Gatti, the founders of Studio 65, were pioneers of Postmodern design, their ironic adaptations of classicism predating most and some of the most effective in favouring fantasy over function.

The Schaudepot, designed by architects Herzog & De Meuron, opened in June of this year. The building holds Vitra’s permanent collection, which includes the estates of Charles & Ray Eames, and Alexander Girard, and hosts a revolving exhibition of key objects.