From 1953 to 1979, the erotic title championed a new wave of architectural modernism that was broadly rejected elsewhere, writes Billie Muraben

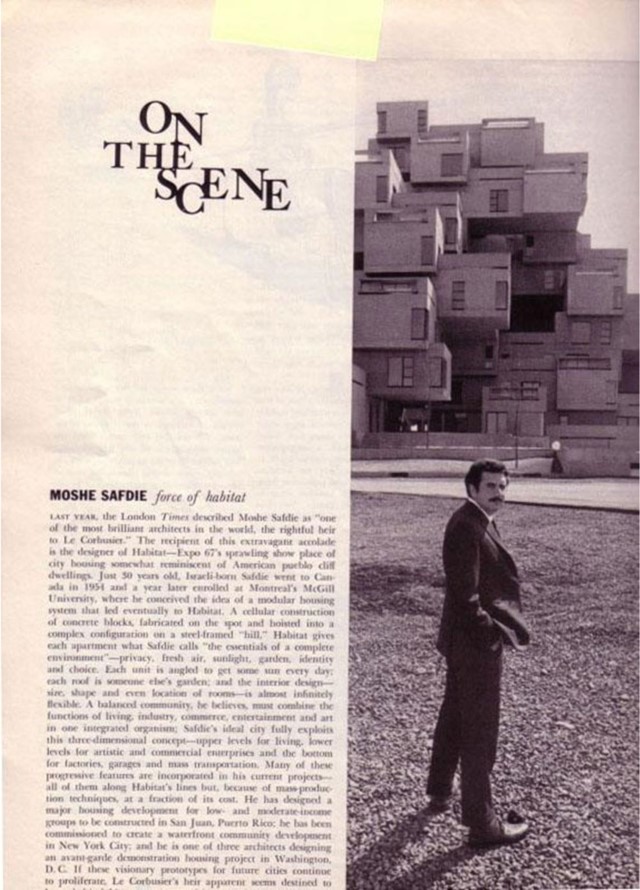

Architecture historian Beatriz Colomina first encountered Playboy magazine’s unexpected legacy in modern architecture by accident. She was interviewing several architects in order to book them for lectures at Princeton University where she runs the graduate architectural history programme, when she realised many of them, and their work, had been featured in the notorious sexy mag. Erotica and architecture make for an unusual pairing, but, she soon discovered, the publication had hosted stories on experimental architects including Paolo Soleri, Moshe Safdie and Ant Farm, as well as the founding fathers of Modernism – Mies Van Der Rohe, Charles Eames, Eero Saarinen and Frank Lloyd Wright.

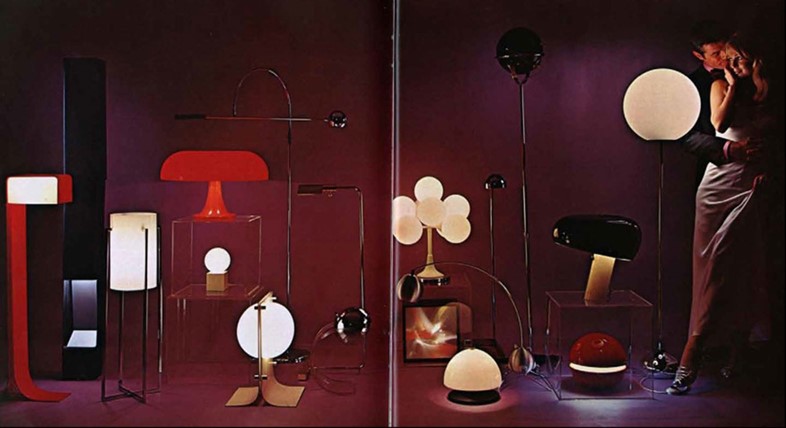

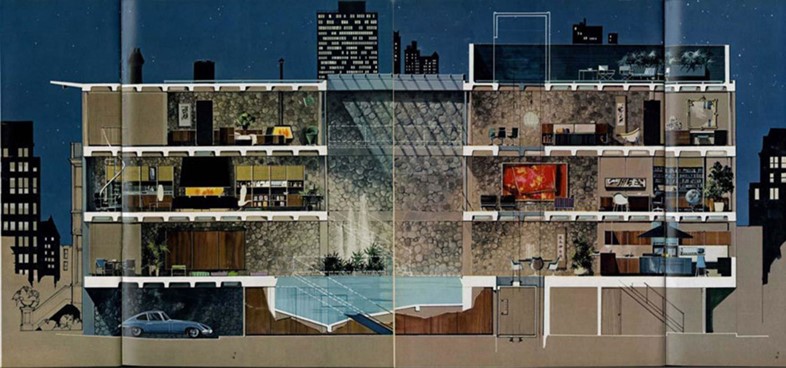

As it turns out, Playboy founder Hugh Hefner had taken his inspiration from the city of Chicago, where modernity played a key part in the city’s skyline. The movement had been broadly debunked by the American architectural press as a European coup to destroy their way of life, but Playboy indulged and promoted Modernism as a glamorous and forward-looking way of living. While the majority of publishers remained conservative in their design and architectural tastes, Hefner claimed the liberated aesthetic as an important tool for seduction.

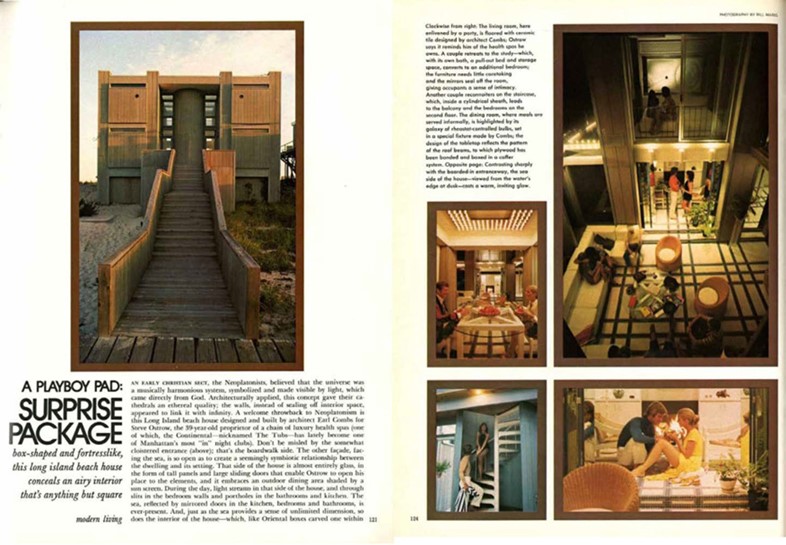

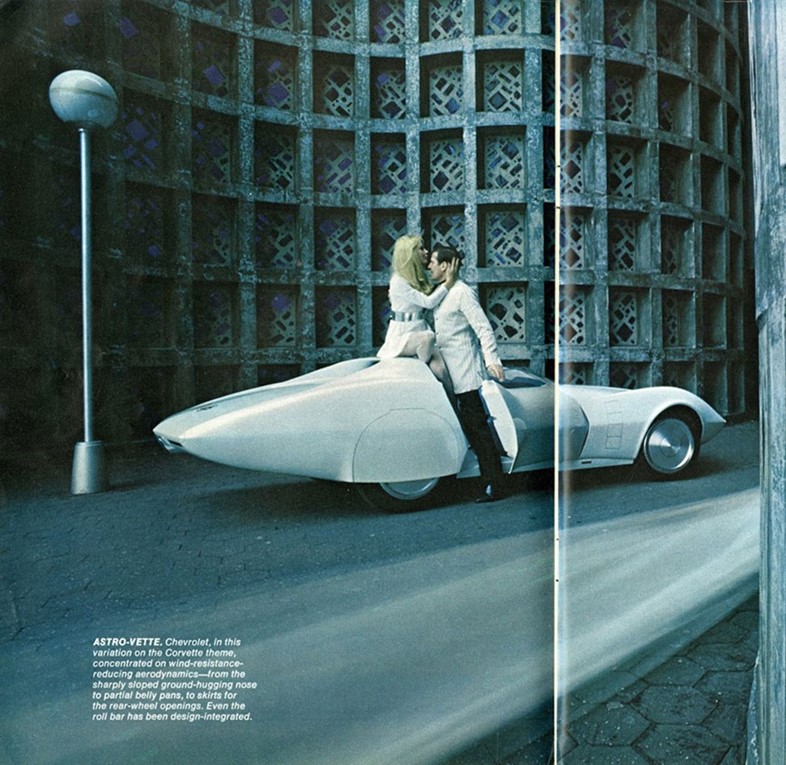

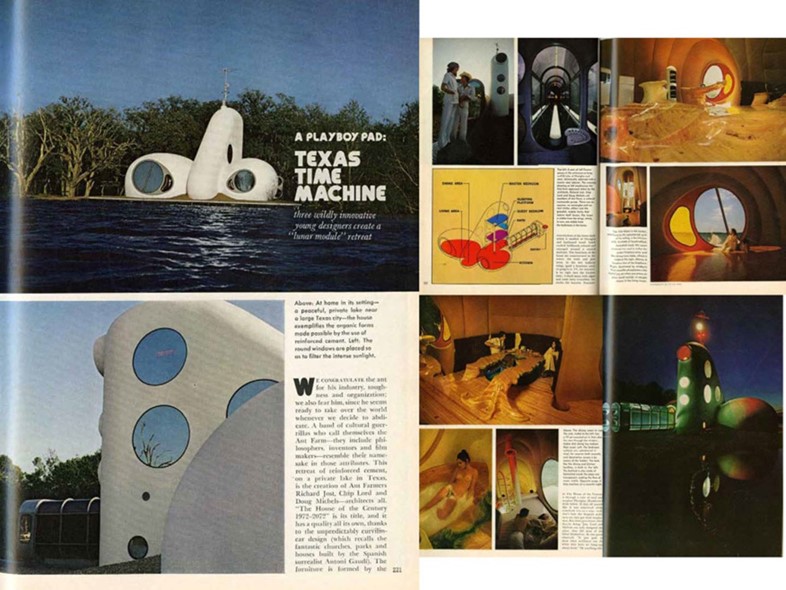

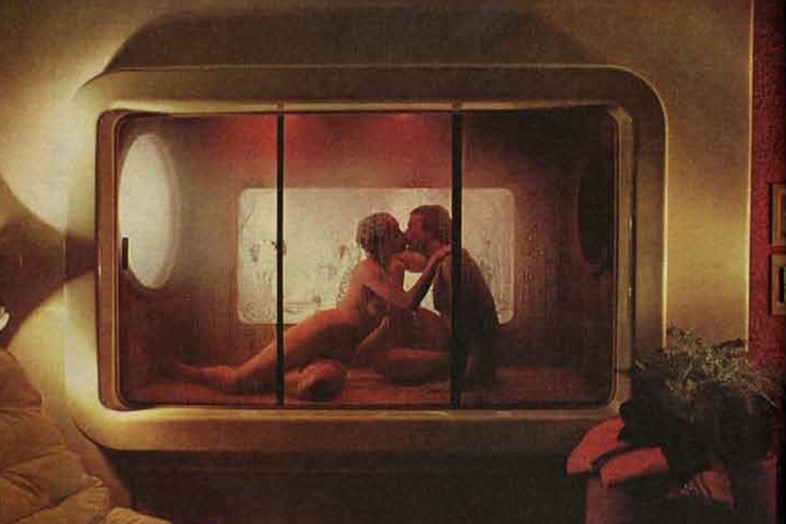

It was over a 20-year period, from 1953 until the late 1970s, that Playboy presented homes as seduction machines, from the Bubble House of Chrysalis to the House of the Century, and then Yale dean Charles Moore’s home. The architects behind them were featured as significant cultural figures, alongside the likes of Vladimir Nabokov, Salvador Dalí and Jean Paul Sartre; and included notes on their zooming sports cars and controversial love lives, too.

But Playboy’s role went one step further than handing out cursory advice, or dressing the magazine up in theory. In Colomina’s opinion, “the magazine did more for promoting modern architecture and design than any architectural magazine or institution”. An early lifestyle publication, Playboy not only defined a new identity for men; what to wear, listen to, drink and read, but also how to engage with design. The features on and of Modernism and radical design conveyed the potential to redesign your surroundings, and respond productively to change. These pieces had a mixed reception, however – historian Sigfried Giedion characterised the movement as “rushing from one sensation to another and rapidly bored”, while Reyner Banham promised he’d “run a mile” for the title. Perhaps these gentlemen really did read the magazine for its taste-making articles, rather than just its bawdy bunnies.