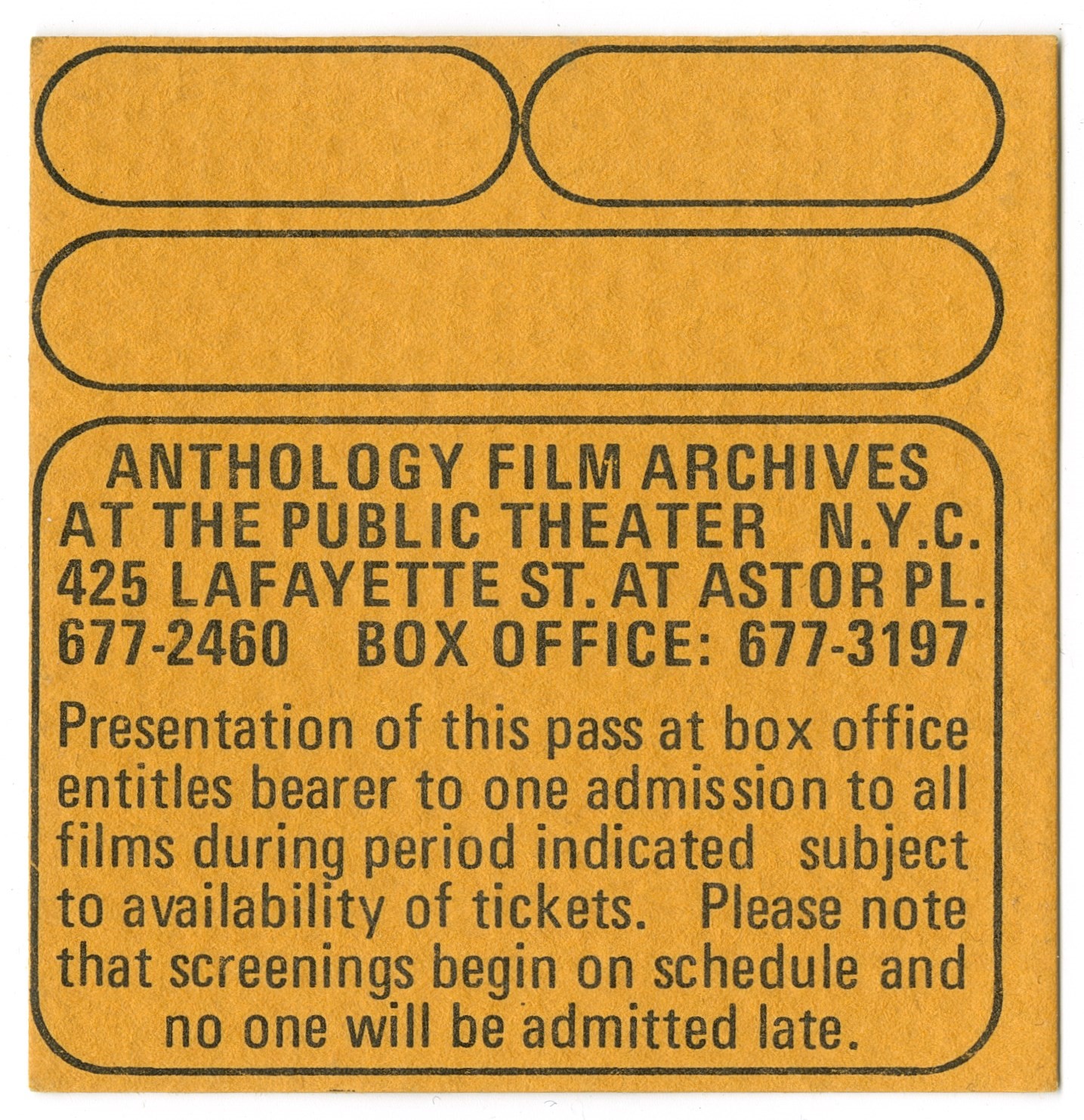

In the ever-changing cultural landscape of New York City, Anthology Film Archives has stood strong as the bastion of independent cinema for the past 47 years. It is one of the world’s largest and most important repositories of independent and avant-garde film and a New York cultural landmark.

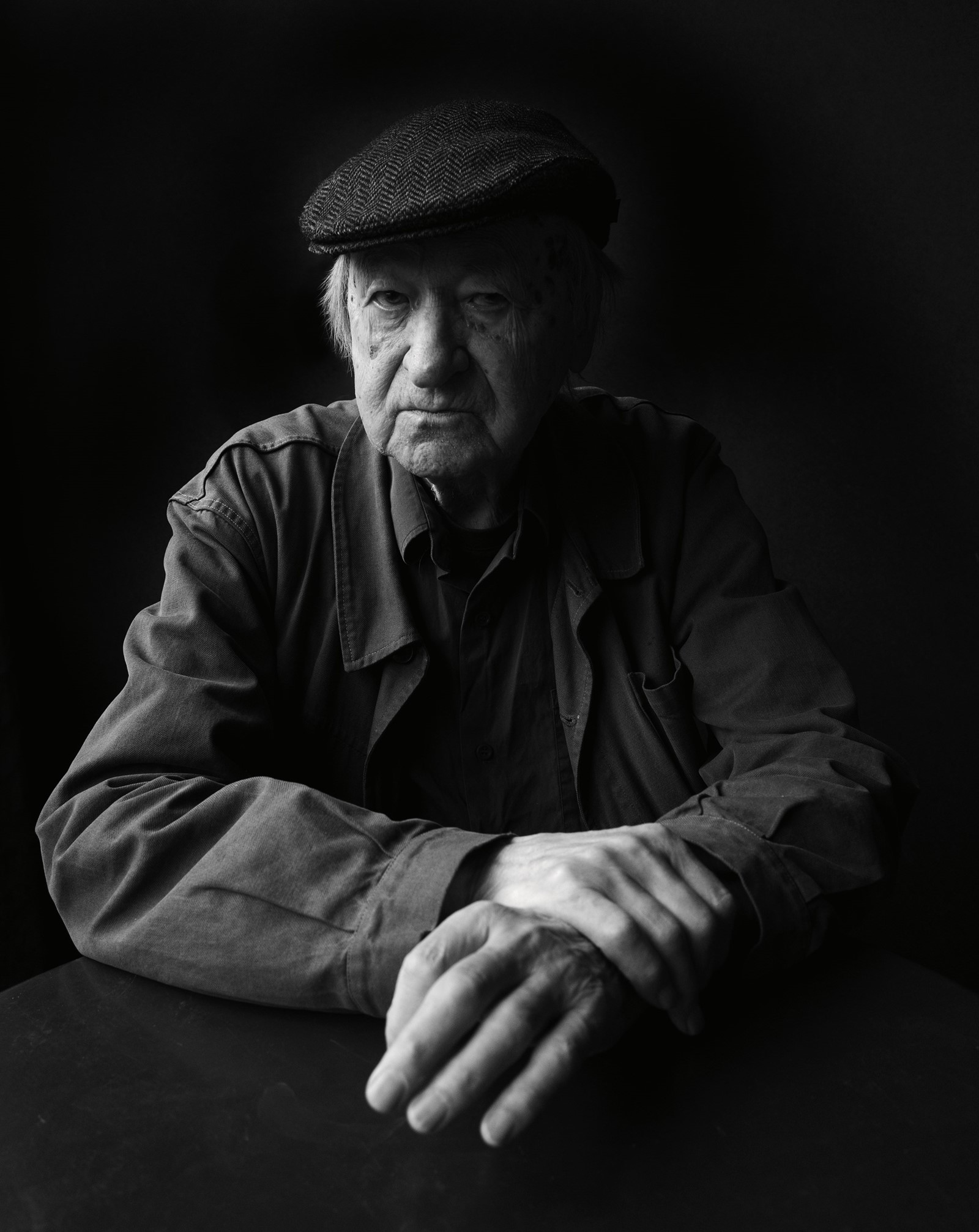

Anthology is about to embark upon an important new expansion project lead by its founding father, the filmmaker Jonas Mekas. Like so much of what Anthology has achieved over the years, it will be a team effort. The international artistic community has come out in force to support the project. Artists such as Chuck Close, Ai Weiwei, Julian Schnabel, Matthew Barney, Michael Stipe, Jim Jarmusch and Patti Smith have all pledged their support for the planned fundraising events. They need to raise $7 Million to secure the future of Anthology along with the films they preserve for generations to come.

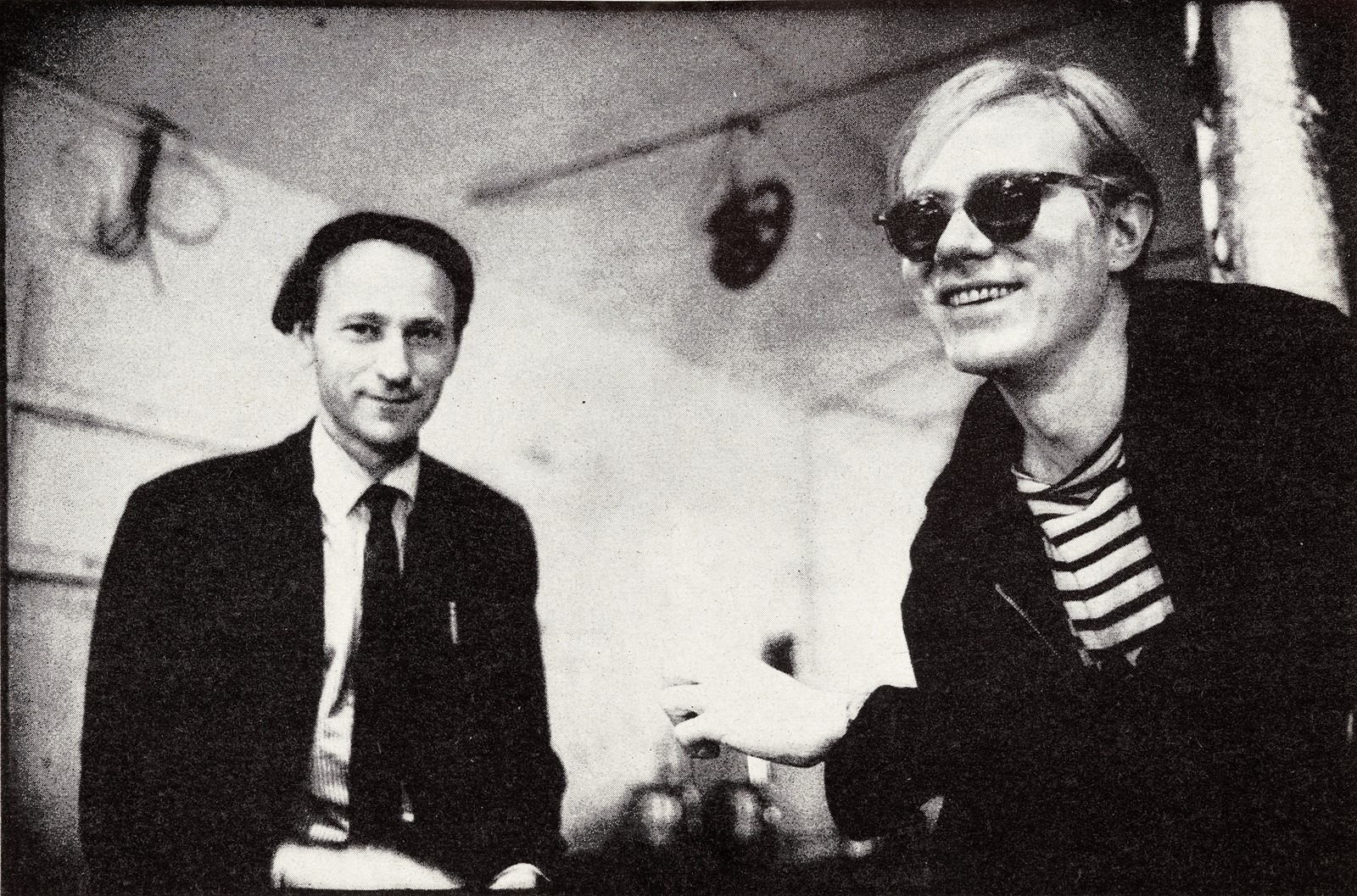

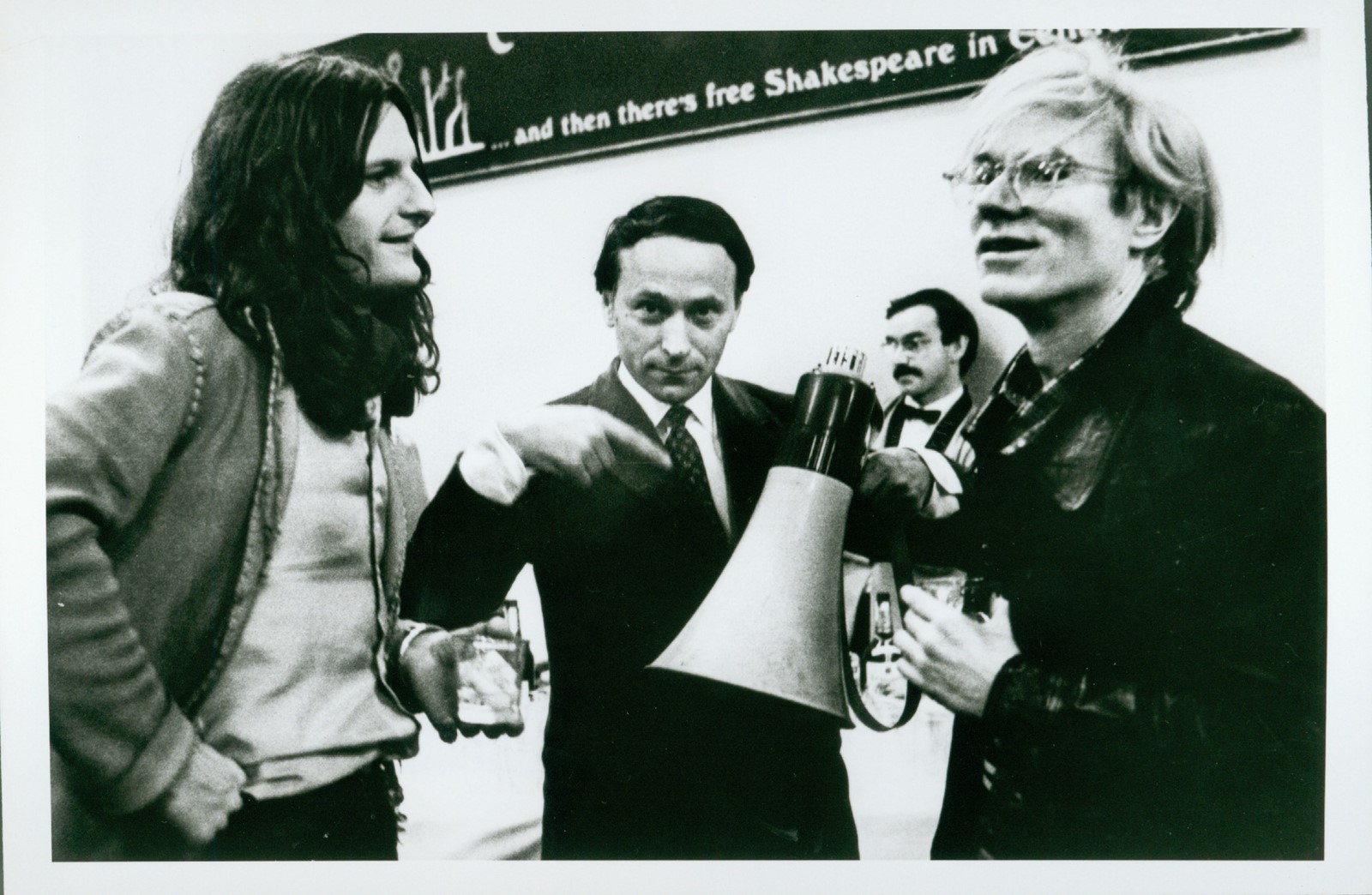

Mekas and Jim Jarmusch first met in the late 70s, both part of an energised downtown film scene still infused by the cultural revolution that swept through New York over a decade before. It was a decade when a fierce independent voice had put cinema in the hands of its makers, changing it forever.

The following conversation took place one rainy day in December. I met Jonas and Jim in the lobby of Anthology Film Archives and we decided to head over to a small bar across the street, on the corner of 2nd avenue. The two began to talk as we walked through the rain…

Jonas Mekas: Where is poetry in your life?

Jim Jarmusch: It’s important to me. I read a lot of poetry. I studied with Kenneth Koch and David Shapiro at the New York School, and I’ve been guided by poets all my life. When I was a teenager in Akron I first discovered the 19th century French poets in translation – Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Verlaine. Parts of my life William Blake has been my guide. I wish someday when I’m gone, someone will consider me a descendant of the New York School of poets, they’ve been my guides because of the sense of humour, the kind of exuberance, you know, of Frank O’Hara –

JM: Yes, Frank O’Hara and Kenneth Koch. They have a humour but there’s also something very real and down to earth. Koch still has to be recognised properly.

JJ: Joe Brainard I love also very much, and Ron Padgett. Ron Padgett wrote the poems for our new film. The character is a poet.

Benn Northover: The character’s named Paterson, right?

JJ: I called the character Paterson, in the film, because of the poem Paterson by William Carlos Williams. He makes a metaphor in the poem of a landscape above the waterfalls there as being like a man. And then I just kept this metaphor; “I’ll make a film about a man named ‘Paterson’ who lives in Paterson, who writes poetry,” you know.

JM: When I first read Paterson I thought that I should meet William Carlos Williams and maybe make a film based on his poems. I knew LeRoi Jones, Amiri Baraka – so we went and visited Carlos. We discussed the project, he had no patients that day. We agreed I would make some notes and then he would make some notes, and then we would meet again. But I do not remember what happened next. Those were the first years of Film Culture magazine, and I became very busy, and I never pursued the project. But I’m curious if some of the Carlos Williams notes would be in his archives. To me he was very important.

JJ: I heard a funny story that Allen Ginsberg, when very young, because he lived in Paterson, gave some of his poems to William Carlos Williams. William Carlos Williams responded but said: “these poems are terrible. You must find your own voice. These poems are rhymed, they’re just not good. But if you desire to be a poet you must continue to work at it. Find your voice.”

BN: Thank God he kept writing. I’ve always loved Emily Dickinson.

JM: I don’t know if you saw, a new book just came out. They’ve published a selection of her envelopes and tiny pieces of paper, where she scribbled little poems or thoughts. It was in today’s New Yorker. She’s my favourite English-speaking poet.

JJ: Ah, one of my favourites, certainly, American poets.

JM: Amazing, what she did with the language.

JJ: So modern and beautiful, amazing. And you read in German and French and English and Lithuanian, of course.

JM: And I can get to Italian and, with a dictionary, Spanish and Russian.

JJ: Kenneth Koch once gave me a poem of Rilke’s, in German, and said “Jim, come back in two days and translate this poem”. And I said “but, Kenneth, I don’t read any German at all”. And he said “precisely”. He wanted me to take anything I wanted. The number of lines, anything, and make a new poem.

JM: What Zukofsky did from the Latin poets – he translated by sound. And of course Robert Kelly did that together with Schuldt. They took Hölderlin’s poem and by sound translated into English, then read the English and by sound from the English – which was already second water from Hölderlin – re-translated it into German.

JJ: Oh wow. Fantastic.

JM: They published the project.

JJ: That’s fantastic. It’s so playful.

JM: We all have those memories: when you don’t know the language and you listen, and you seem to understand, but you get completely something else. Yet the amazing thing is, like with Zukofsky’s translations and the same with what Robert Kelly and Schuldt did with Hölderlin – you get some of the same spirit, there is something that remains.

JJ: I think it was E.E. Cummings who said, “You can understand a poem without knowing what it means”.

JM: The same with music and films in a language you don’t understand. Somehow you know what the characters are feeling and saying.

JJ: When I went to Japan in the 80s I was obsessed with Ozu and Naruse and Mizoguchi. I couldn’t get their films here, so I bought so many on VHS but they were, of course, not translated. I would watch them endlessly without any knowledge really of the dialogue at all, but I still would understand so many beautiful things and I learned a lot about acting and people’s eyes and camera positions, and just the tiny ways you make a film.

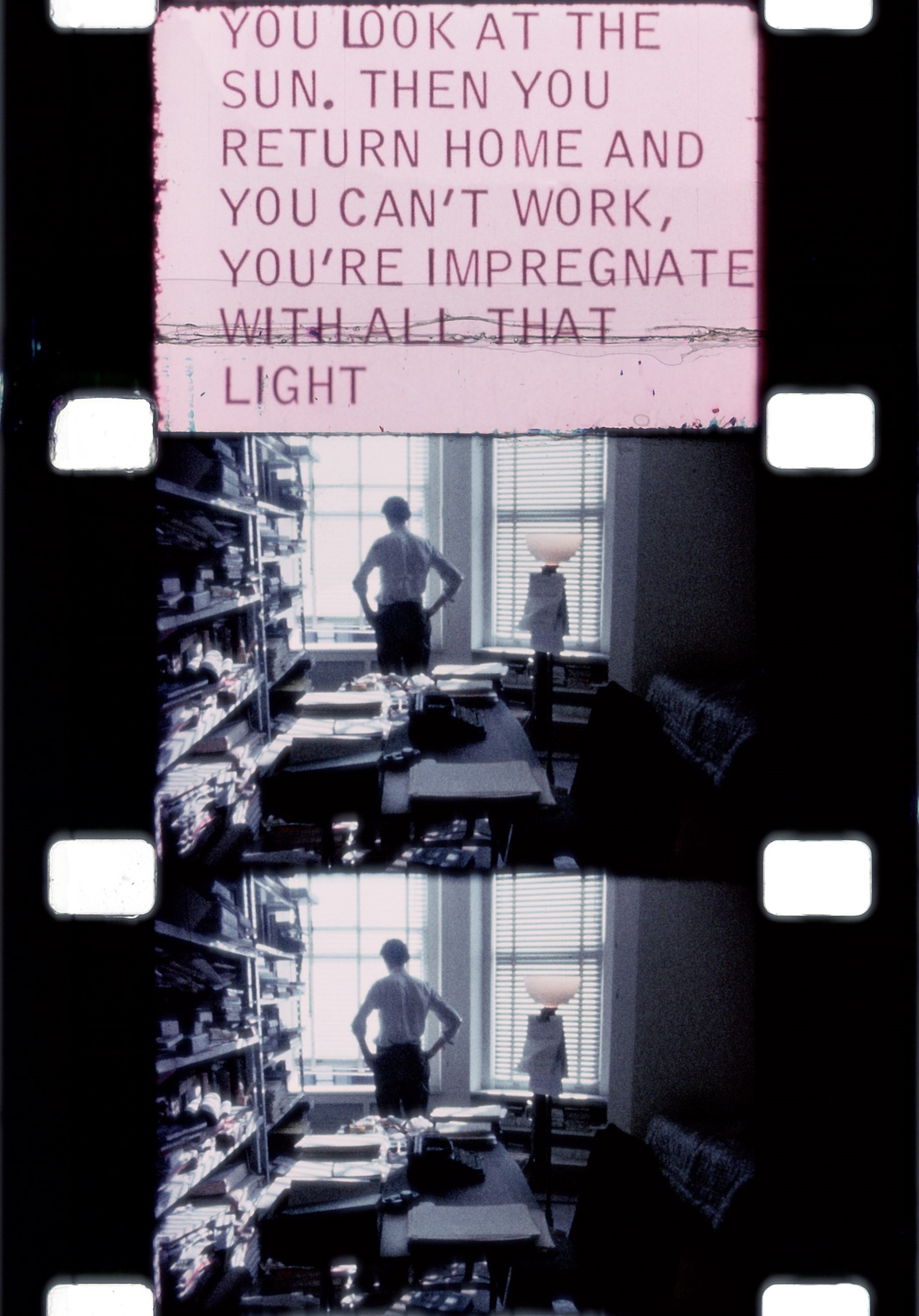

JM: People say you should not watch video copies of the films. But sometimes that is the only way for somebody in a remote part of the world to see those films. It’s the same in art. When I went to primary school in a remote village in Lithuania, there was a shelf full of books, and there was one book on Renaissance art. It was on black and white, miserable paper and already old. I was so impressed with those miserable black and white reproductions; I always wanted to see the originals. Somehow in those miserable reproductions, the essential came through. So I’m not against films made available for information and on digital materials, as long as there are places like Anthology Film Archives where they can still be seen and projected film as film, or video as video.

JJ: I was just looking through a small amount of different artists – film artists – that you have preserved or celebrated. This is only a small amount of people that have really moved me: Peter Hutton, Hollis Frampton, Nam June Paik, Bruce Conner, Hans Richter, Taylor Mead, Danny Lyon, Rudy Burckhardt, Shirley Clarke…

JM: And we have not only their finished films, but unfinished materials. Outtakes of Hans Richter, Maya Deren, Hollis Frampton and even Tarkovsky.

JJ: … Man Ray, Joseph Cornell, Robert Frank, Harry Smith, Jack Smith, George and Mike Kuchar, Kenneth Anger, Lizzie Borden, Stan Brakhage, Bruce Baillie, Ron Rice, Michael Snow, Andy Warhol, Ken Jacobs, Maya Deren… on and on.

JM: Anthology is the bastion of poetry and cinema and we are here to stay. This is the building where the poets of cinema live. It is a metaphor, this building.

JJ: I love that. It’s a very strong metaphor: we’re not going away, you know, we are here. I always thought, visually that it is a badass piece of architecture. I wanted to ask you about the name, because I’ve always loved ‘Anthology Film Archives’, because ‘Anthology’ is sort of anti-hierarchical in a way.

JM: Myself, Stan Brakhage and P. Adams Sitney, we all came from a background of poetry. The first idea was to establish an essential list of films that have contributed something to what is known as the ‘art of cinema’, to establish an anthology of the films we love and are willing to defend with our bodies and our minds and all our passions. Researchers often come from Europe because they cannot find the materials we have anywhere else. Not only the film materials but also the extensive paper material collections in our library. This includes publications, periodicals, scripts, correspondences, filmmakers’ working materials. We have for instance, the original shooting script of Citizen Kane, with Orson Welles’ notes, cross outs. Things like that. We have Joseph Cornell’s working materials: magazines, books from which he cut out angels and stuff that he used in his collage work. But we also have hundreds of boxes of materials that are not available to researchers, as we simply do not have the space. This is why right now we’re trying to raise money to expand the Anthology building. We have all these materials and nobody can see them, it’s very important we build our library.

JJ: And the library will be on top?

JM: Yes, one new floor on top of the current building.

JJ: Fantastic.

JM: We will also improve film and video archival facilities and will have a gallery space so we can protect, preserve and display all these incredible materials properly. As well as improving the two film theatres we have now.

JJ: It’s incredible.

BN: It seriously is. It has to happen.

JJ: It has to happen.

JM: All of this is now a seven million dollar project. That’s why right now I am in the process of organising an art auction, trying to raise those seven million... I really hope that between the auction and donations we can raise the budget needed to compete the project. So for the past months it’s been my main job to get artists and collectors involved. I’m working hard and I’m sometimes not sleeping nights.

JJ: Well it’s got to happen. I remember when you were struggling years ago, when you were just starting to renovate – we shot the first Coffee and Cigarettes there. I didn’t realise until I was just reading up more about Anthology Film Archives, this gangland murder that took place in 1923, right outside the front doors of what is the Anthology building. Where a guy, a young gangster named Kid Dropper was assassinated by Louis Cohen – a notorious gang member – and he killed him right outside of the doors there.

BN: Of course, it was a courthouse.

JM: The building was built in 1914 and the original plans were for a 12-storey building. But the war started, so the building remained on two and a half floors. The structure as it stands now is very strong and could carry another ten floors.

JJ: Wow, fantastic.

JM: So next to the library, we are going to build a café, which my dream is, should become like a tribute to Café Voltaire and Café de Flore.

JJ: Oh man.

JM: We want to make it very very special.

JJ: I want a new hang out, and I need a new hang out.

JM: Yes. Yes. There is no place right now in New York where, you know, poets, filmmakers can go – like in the 60s there were several. Now there’s no place. Can you name one?

BN: No.

JJ: In Williamsburg?

JM: But we need one in Manhattan. We need one in downtown Manhattan. It will be just wine, good simple food – not a restaurant. It will be a café like some French bistros.

BN: And with good coffee!

JJ: Well that would be fantastic.

JM: The ‘cathedral of cinema’ will be completed. The cinema is like a big tree with many different branches, and although Anthology’s mission is to serve primarily the independents and the avant-garde, the cinema of poetry – we are equally devoted to all of the branches of the tree called cinema. Of all styles, forms, periods, genres, countries.

JJ: We mentioned the people whose work has been preserved, but we also have to mention how incredible a living place it is, with an incredible catalogue of programming and amazing people coming through and speaking, appearing, presenting. So there’s this preservation that’s so important for these kinds of films, but there is also the living thing – that’s why I love the café idea. There’s value to all of these things. It’s like molecules of so many things there. And history too. Can I ask you, how do you feel about the present? When you think about all these people that you’ve known and worked with, do you still feel optimistic about the present and artists?

JM: I’m always optimistic because the future is always full of possibilities. It can go bad or it can go well. But then you see I was very involved during the past 60 years, very involved in whatever was happening. I’m less involved now in what’s going on. But I must say that I don’t feel that much passion and craziness in the contemporary art-making generation of today. You see, my feeling is that we are still in a period, which I describe from Joseph Conrad, as after ‘the shadow line’. Before the shadow line you don’t care what you do, you just do it. No matter who says what, you just do it. “Fuck you I’m doing what I do.” But after the shadow line it becomes reverberation, it’s like so much is being done after the black square and after abstract expressionism and after Warhol, that is just reverberations. I feel we are still in this transitional period when we have so much respect for all that, that we are re-hashing the same. There is no new explosion. We need like a new booster. But I think that the computer – there is something to that, there in this computer generation, I think there is something new beginning that is there.

JJ: We’re waiting for the explosion.

JM: Yeah, I think we are before the explosion.

JJ: And are you worried, as cycles of history, are you worried about repression of speech and ideas?

JM: I don’t think it will happen. I think that people will protest. I don’t think Trump can do what he wants to do; I don’t think he’ll be able to. We have to see what he does, and that’s when the people will revolt. If he does something against immigrants or women – they will really fight him. When people rise up with passion, anything is possible.

BN: Very true.

JM: I will show you what I’m reading now. I don’t know if you know Paul Celan’s poetry, he is one of the great German language poets. I found one of the best recent descriptions of what poetry is in this book. You can read the whole passage silently for yourself. But he ends with this; “The search for ground lights is not enough. There is the axis to be followed and ‘—dot dot dot—’ forgotten. You must above all find lightness, buoyancy, the permanent defiance of gravity.”

JJ: That’s fantastic. The permanent defiance of gravity.

Jonas Mekas and Anthology Film Archives will present a landmark gala and art auction, featuring a performance by Patti Smith, in New York on March 2, 2017 at Capitale in support of the Anthology Film Archives Heaven and Earth Library & Café Expansion Project. Visit the website for tickets and more information.

With very special thanks to Nancy Waters, Arielle de Saint Phalle and Carter Logan.

This interview is an extension of one which originally featured in AnOther Magazine S/S17, out now.