As Julie Dash’s 1991 masterpiece Daughters of the Dust is re-released, we remember some of the women whose daring work forced change in a male-dominated medium

Last month saw Julie Dash’s seminal film Daughters of the Dust return to cinemas, in a gloriously restored version, 26 years after its official release and a year after it was brought to the attention of a younger audience as a key inspiration for Beyoncé’s Lemonade video. Centred on a frequently forgotten chapter of African-American history – the last bastions of Gullah culture (the Gullah were descendants of West African slaves) off the coast of South Carolina – Dash’s poetically rendered story traversed bold new territory in the cinematic representation of black women. It also broke new ground as the first full-length feature by an African-American woman to obtain general theatrical release in the United States. Here, as the film arrives on DVD and Blu-Ray, we spotlight eight female filmmakers (Dash included), whose pioneering contributions to the medium helped change the shape of cinema forever.

1. Alice Guy-Blaché

French filmmaker Alice Guy-Blaché was a contemporary of the famed Lumière brothers, and was in many ways just as influential in the invention of cinema, yet 49 years after her death, she remains widely unknown. Guy-Blaché first encountered the new medium as the secretary of Léon Gaumont, founder of the Gaumont film studio. She apparently expressed boredom with the nonfictional “demonstration films” being produced by the studio and asked permission to make her own work, with a fictional storyline. The resulting work, La Fée aux Choux (The Cabbage Fairy), made in 1896, tells the whimsical tale of a woman who grows children in a cabbage patch and is widely considered the first ever narrative film. Guy-Blaché went on to make over 1000 films during her lifetime, driven by what she dubbed “fertile imagination”, and is thought to have coined the idea of filming on location as well as shooting one of the first close-ups.

2. Dorothy Arzner

Dorothy Arzner began her career typing scripts in a male-dominated Hollywood, but within six months had climbed the ranks to editor, later turning her hand to scriptwriting. In 1927, she was offered the chance to direct her own feature for Paramount, while other women were being confined to the roles of costume and set designers or make-up artists in the steadily burgeoning industry. Arzner produced four popular silent films for the studio before being asked to direct their first talkie, The Wild Party, starring Clara Bow – she supposedly invented the boom mic during the shoot to help the actress overcome her fear of speaking on camera. Arzner spent 15 years in the director’s chair, working with some of Hollywood’s most iconic stars, from Katharine Hepburn to Lucille Ball and Joan Crawford, and becoming the first woman to join the Directors Guild of America. To this day she remains the most prolific female studio filmmaker in the history of American cinema.

3. Germaine Dulac

Feminist writer and journalist Germaine Dulac first turned her hand to film in the late 1910s, founding her own Paris-based film company D.H. Films. She gained initial recognition directing serial melodrama Âmes de fous (1919), but soon took interest in the newly emerging French Impressionist movement in film, going on to become one of its most important pioneers. Her most famous work, La Souriante Madame Beudet (1922) – the story of a woman trapped in a passionless marriage, with dreams of escaping – is often hailed as the first feminist film, while many consider her fantastical 1929 film La Coquille et le Clergyman a precursor to the Surrealist work of Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí. Dulac went on to make many other influential works centred on the idea of “pure cinema”, which championed film as a medium entirely separate from the influences of painting and literature. Unfortunately her career did not survive the transition into sound cinema and she spent her later years producing newsreels for Pathé and Gaumont.

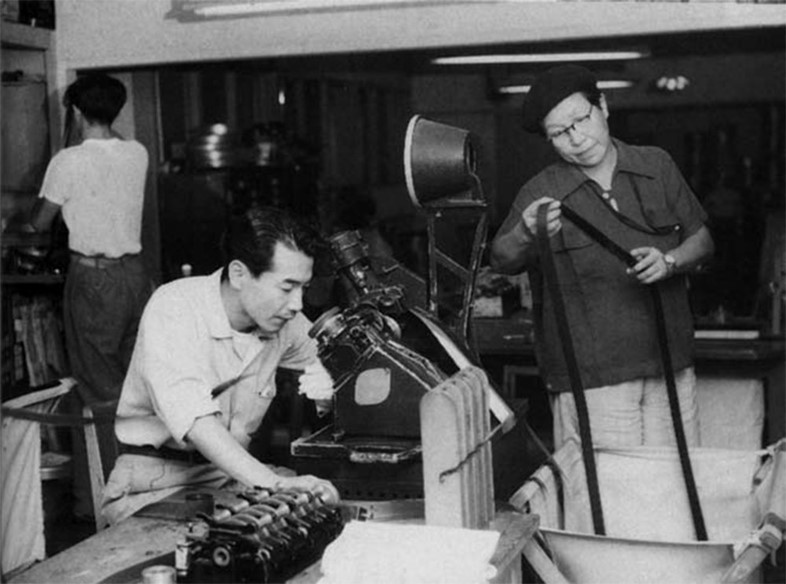

4. Tazuko Sakane

Tazuko Sakane was Japan’s first female director and one of the world’s first documentary filmmakers. Born in 1904, Sakane developed her love of cinema from her film fanatic father, who later introduced her to feted director Kenji Mizoguchi. Mizoguchi hired her as a script girl, before spotting her creative potential and promoting her to editor and assistant director. Despite this early endorsement, Sakane faced severe harassment from the rest of her male colleagues – so much so that she cut her hair short and wore men’s clothing in an attempt to fit in. In 1936, aged 32, she directed her first feature film Hatsu Sugata, only fragments of which still exist. During the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, the filmmaker travelled to the Chinese region to make pioneering documentaries about the ill effects of war. Once the conflict ended, however, it was decreed that all Japanese filmmakers must possess a university degree, and Sakane was forced to return to her role as editor and script writer, until her retirement aged 46.

5. Maya Deren

Ukrainian-American director Maya Deren was one of American cinema’s most brilliant experimental filmmakers. A woman of many talents – she was also a dancer, choreographer, poet, writer and photographer – she translated her love of dance, Haitian Vodou and subjective psychology into a number of surreal, black and white shorts. Deren was a tireless innovator, employing various camera techniques, such as multiple exposures, superimposition, jump cutting and slow-motion, to conjure an idiosyncratic stream of consciousness on film. She was a vocal critic of the Hollywood film industry throughout the 40s and 50s, describing it as “a major obstacle to the definition and development of motion pictures as a creative fine art form”. She instead based herself in New York, where she rubbed shoulders with fellow avant-garde visionaries Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, André Breton and Anaïs Nin, the former two going on to feature in her work. She died at the young age of 44 from a brain haemorrhage, but her legacy lives on as one of the key founders of the New American Cinema.

6. Barbara Loden

Barbara Loden first rose to fame as an actress and pin-up girl in 1950s New York, commanding attention with her striking, coquettish looks and considerable theatrical prowess on Broadway. She was discovered for films by famous producer/director Elia Kazan, who cast her alongside Warren Beatty in 1961’s Splendor in the Grass. She continued to secure roles in a number of big productions over the next few years, but after marrying Kazan, and following the commercial flop of her 1968 film Fade-In, went into semi-retirement. Loden returned to the spotlight two years later with independent film Wanda, which she wrote, directed and starred in – the first woman to take on all three roles in conjunction. An extraordinary portrait of female alienation, the movie was wildly hailed as an art house masterpiece, winning the Venice Film Festival’s International Critics Prize. Its popularity placed Loden among the few female directors whose work was theatrically released during the period, but sadly she never followed up on its success, supposedly discouraged from doing so by her possessive husband. She died from cancer in 1978.

7. Monika Treut

German filmmaker Monika Treut is a vital trailblazer within the realms of queer cinema, as well as a feted documentarian. Treut began experimenting in video in the 1970s, but it wasn’t until she had finished her studies in philosophy in 1984, that she pursued film full time, co-founding her own production company, Hyena Filmproduktion, with Elfi Mikesch the same year. She and Mikesch made their feature debut the following year with cult classic Seduction: The Cruel Woman, a fictional investigation into sadomasochistic sex through the eyes of dominatrix, Wanda. Treut released her first solo venture, coming-out story Virgin Machine, in 1988 and has continued to make waves with her transgressive output ever since; as Sight and Sound’s Julia Knight noted, “her misbehaving women [continue to serve as] a vital form of resistance” in the arena of sexual politics. Treut’s documentaries cover a broader scope, taking on subjects as varied as the culinary arts of Taiwan and the plight of street children of Rio de Janeiro, alongside queer themes. Nevertheless, they are all linked by the distinctly candid, personal approach that so sets Treut’s fictional films apart.

8. Julie Dash

Last but not least, there’s Julie Dash, whose aforementioned movie Daughters of the Dust tells the story of three generations of Gullah women as they battle with the decision of whether or not to leave their home, on an island off South Carolina, in favour of mainland life. The film sees Dash present a uniquely feminist perspective that employs image, sound and African storytelling traditions as a means of championing the strength and beauty of black women. The director’s early films were non-fictional – think: her acclaimed dance film Four Women (1977), based on the song by Nina Simone – but as time went on, inspired by the writing of black American authors, she began to dream of telling fictional stories. “I stopped making documentaries after discovering Toni Morrison, Toni Cade Bambara, and Alice Walker,” she once told The Village Voice. “I wondered, why can't we see movies like this? I realised I needed to learn how to make narrative movies.” Dash has since made a number of acclaimed TV series, including The Rosa Parks Story, as well as various music videos, and is currently working on a documentary titled Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl to be released later this year.

The newly restored version of Daughters of the Dust is available on Blu-Ray and DVD from today.