A new Florence exhibition traces Salvatore Ferragamo’s inimitable impact on Italian culture

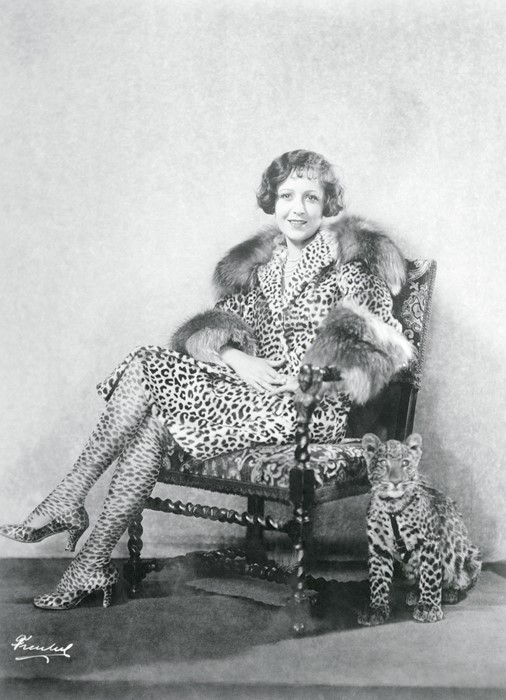

Last week at Azzedine Alaïa’s triumphant return to the couture calendar in Paris, models walked the runway with leopard-print legs. It was neither a surreal hosiery trick nor make-up that was responsible, but rather cleverly crafted thigh-high boots, first created more than 90 years ago by innovative shoe designer Salvatore Ferragamo. The 1925 Indiana is “one of those creations that have written shoe history,” in the words of Stefania Ricci, the director of the Museo Salvatore Ferragamo, and just one piece of evidence in the mounting case that Ferragamo was constantly ahead of his time.

First worn by the Hollywood star Lola Todd, who dressed from head-to-toe in the vivid print and accesorised with a matching pet leopard, these shoes are in many ways emblematic of Ferragamo’s inventive and restless spirit. Now, 90 years since his return to Italy in 1927, the Museo Ferragamo presents an overview of his legacy. It was “a time full of very important social changes,” Ricci notes. In many ways the 1920s were “a forge of open-minded ideas and experimentation, free of ideological constraints and prejudices” that would shape the years to come. In Italy, especially, this was a period of incredible productivity, and Ferragamo’s return was symptomatic of that revitalising change.

The roaring 20s in Italy saw a vibrant return to tradition and order in the arts. “From 1923 onwards, the Monza Biennial exhibitions dedicated to the decorative arts were presented not just in Italy but to the whole world,” Ricci observes. It was at this time that an Italian taste took shape, along with the notion of national pride that proved crucial for the development of Ferragamo’s empire.

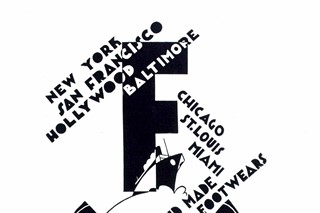

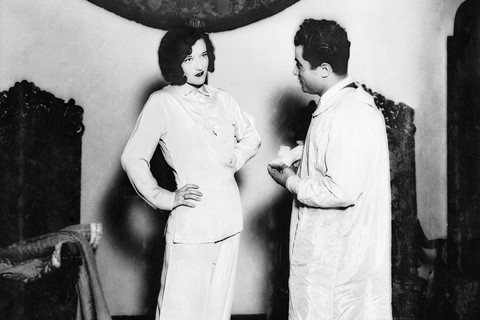

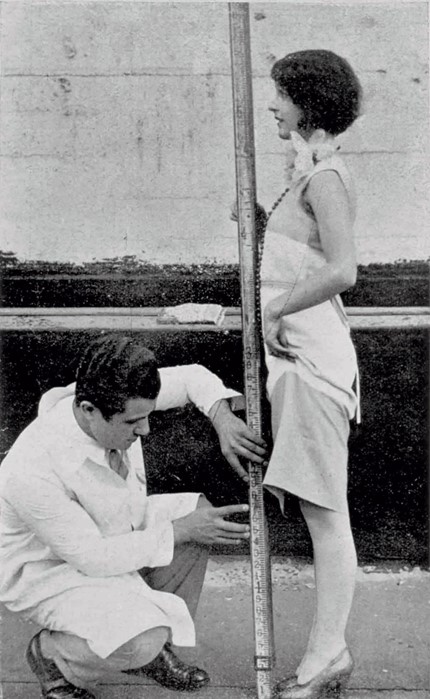

Back in 1915, at the tender age of 17, Ferragamo had left the small Italian village of Bonito where he was born, and boarded an ocean-liner from Naples to the United States. In a time when America’s doors remained open to immigrants, the determined Ferragamo saw the new world as a true land of opportunity. On arriving in California he attended university to study the anatomy of the foot, and his meticulous attention to measurements ensured his shoes soon garnered a reputation for comfort as well as style; before long he was dubbed “shoemaker to the stars”. Ricci is adamant that Ferragamo’s ties with the entertainment industry changed his life by allowing him to create custom-made designs for the leading ladies of the day, each with their own personality: crocheted multicoloured raffia uppers and brass heels for Joan Crawford; low shell-shaped slip-ons for Audrey Hepburn; crocodile skin pumps for Marilyn Monroe. For the young designer in the Golden Age of Hollywood, nothing was out of reach.

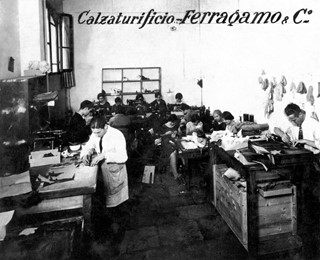

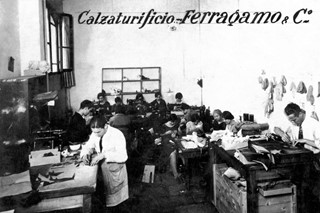

Ferragamo chose Florence for his return. This move reflected not merely the city’s historical importance as the birthplace of the Renaissance, but acknowledged its newfound centrality in the geography of Italian taste and style. The city became the epicentre of Ferragamo’s vision for the future; he quickly became the head of a company producing over 350 shoes a day and employing around 750 shoemakers – a far cry from the skilled 11-year-old with a team of six serving a village in Irpina in the remote Neapolitan countryside.

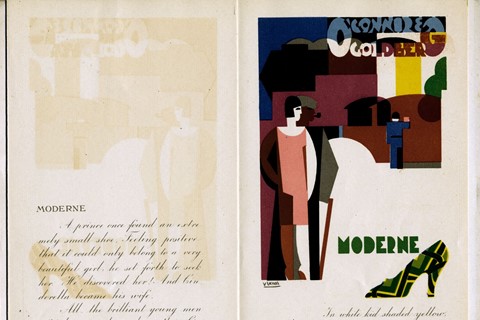

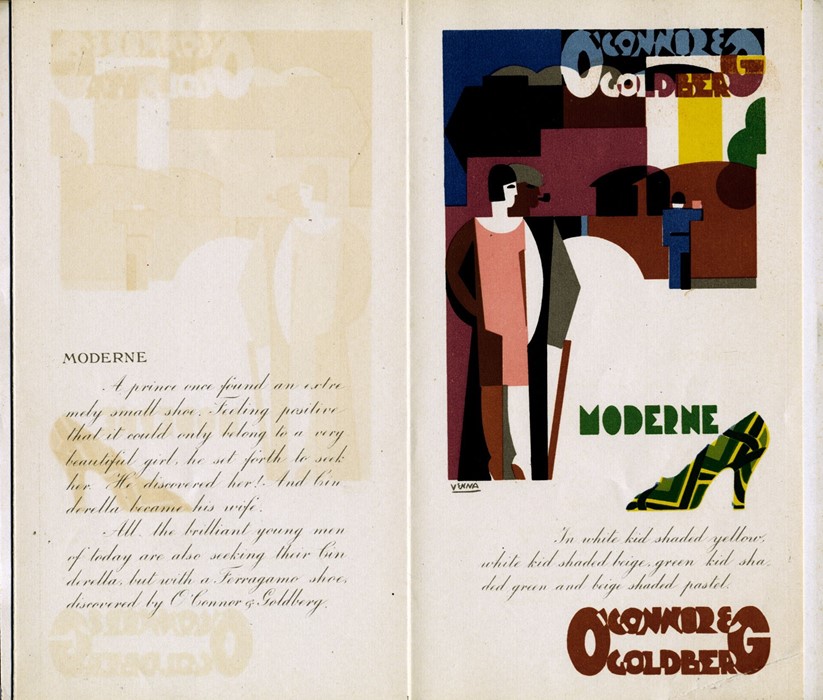

When Ferragamo made his move back to Italy, he did so with an acute awareness that the identity of la donna was transforming in the post-war period, with shorter boyish haircuts and loosely cut drop-waists coming to define women’s dress, as the exhibition reveals. Combined with the rising vogue for energetic dances, styles like the foxtrot and charleston presented a liberating freedom, with vigorous swinging of limbs which in turn required shoes that could take the pressure and keep people dancing all night long. In many ways Ferragamo was designing shoes for the 1920s all along. These were shoes that didn’t just look the part, but ones that could take people places.

Despite its broad themes, every piece in the exhibition is fundamental in Ricci’s eyes, with Ferragamo’s designs seated comfortably between works by the likes of Gio Ponti and Mini Maccari. “The final result is given by the synergy,” she explains. It’s certainly an immersive experience; it takes the metaphor of Ferragamo’s ocean voyage and transforms the exhibition space into a journey all of its own. Rows of shoes are hung delicately on white ship-style ladders against white-washed walls, hand-painted heels set against colourful canvases, and moody black and white images of favoured customers hung aloft in porthole portraits.

Ferragamo left Italy as a third-class passenger, but he returned in first, a world away from his original journey into the unknown. Yet despite his new fame, Ferragamo’s opulence remained firmly rooted in his rustic heritage. He opted for experimentation in his designs, utilising traditionally poor materials; his inventive eye led him to recast fishskin, straw, and cork for shoes that soon had the elite hooked. Italy offered the kind of craftsmanship that the young designer could not find in America. While searching for security he rediscovered his heritage and the Italian art, materials, craftsmanship and tradition that would foster his own values for, in Ricci’s words, “creativity, beauty and wellness”.

1927 The Return to Italy: Ferragamo and 20th-Century Visual Culture runs until May 2, 2018 at the Museo Ferragamo, Florence.