The V&A celebrates its links to the legendary designer with the Alexander McQueen Research Library – a resource collating the books that played a powerful role in his work

Alexander McQueen’s mind was full of preoccupations – one only need look at the scope of his collections for evidence – and fed by a voracious appetite for discovery. He was a hoarder of references – in his studio, pattern books from the 16th century would sit next to piles of National Geographic magazines; photographs of death masks, coral, globes and clock faces might be pinned to the walls, and a well-thumbed copy of McDowell’s Directory of 20th-Century Fashion was frequently called upon (according to current creative director Sarah Burton, it was his favourite book). In McQueen’s collections, these idiosyncratic artefacts would be woven together like a vast web of firing neurons.

It is little wonder, then, that McQueen found solace in the cavernous halls of the V&A museum – “It’s the sort of place I’d like to be shut in overnight,” he said of the central Cass Court – and would spend hours discovering the treasures within. His relationship with the museum would prove fruitful, too – the designer participated in Fashion in Motion twice; in 2001 his work was featured in the era-shaping Radical Fashion exhibition and in 2003 he created the museum’s annual Christmas tree, a hovering crystal chandelier which hung conspicuously in the Great Hall.

Sitting within the museum is the National Art Library, a reading room that constitutes the UK’s most comprehensive resource on the decorative arts (further parts of the collection can be found at Blythe House, Olympia). Now, almost a decade since McQueen’s death and in the aftermath of the record-breaking Savage Beauty exhibition held at the museum in 2015, the NAL felt the time was correct to celebrate his legacy once again. So, “Alexander McQueen’s Research Library” was born – a resource which collates the books which informed the designer’s work, and which it holds in its collection.

“We matched books from McQueen’s personal library with the NAL’s catalogue and displayed these next to his original sketches, patterns from Plato’s Atlantis and show invitations,” Louise Rytter, the assistant curator of Savage Beauty, who collaborated with NAL librarian Sally Williams on the project, tells AnOther. “[McQueen’s] research boards are a testament to his passion for research and storytelling, a gateway into understanding his defiant vision, the technical artistry of his designs and the dramatic intensity of his fashion shows.” Here, five of those books – and the ways they defined McQueen’s work.

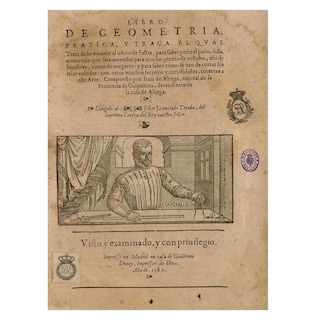

1. Libro de Geometria, Pratica y Traça by Juan de Alcega (1589)

After working on Savile Row in the mid-1980s, McQueen undertook a brief stint at Berman’s & Nathan’s, a theatrical costumers in London. Though his time there was short, it would leave an imprint on the young McQueen – if simply for the introduction it gave him to Juan de Alcega’s Libro de Geometria, Pratica y Traça, a 16th-century facsimile of patterns from the Spanish tailor, published in 1589 on the permission of the king of Spain. It solidified, if not began, a lifelong preoccupation with the trappings of historical dress, which would continue to underpin his work until the end. The traces of the facsimile, of which the NAL owns a rare copy, were felt in his A/W96 Dante collection, where the cut of articulated jackets seemed a direct reference to Alcega, though examples can be found throughout his career. He would go on to collect historical pattern books obsessively – another favourite was Nora Waugh’s The Cut of Men’s Clothes 1600 –1900.

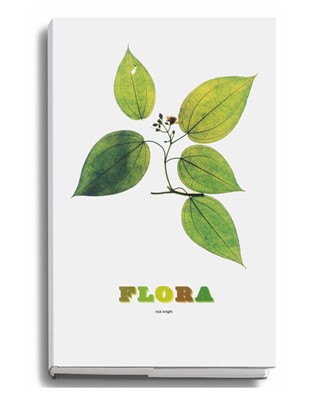

2. Flora by Nick Knight (1997)

McQueen and photographer Nick Knight shared a impactful creative relationship – collaborating on a series of boundary-pushing photoshoots for Dazed, Visionaire and Numéro, among others, Knight helped define McQueen’s visual landscape, rebuking what the pair saw as the era’s “dull visions of women”. They worked fruitfully up until McQueen’s death – Knight’s SHOWstudio provided the livestream for his final show, Plato’s Atlantis, long before such a democratisation of the fashion show became the norm.

Outside of their collaboration behind the camera, Knight’s influence can also be seen on the clothes themselves – for McQueen’s Givenchy Spring/Summer 2000 haute couture collection, a white silk, bias-cut gown was decorated with a pink floral print from Knight’s series Flora, a collection of photographs of dried flowers from the Natural History Museum’s herbarium. That photograph in question was of red algae, found 250 metres under the ocean – a plant which gets its unique pink colour from its photosynthetic absorption of blue and green light, speaking directly to McQueen’s fascination with the nature, and its strange oddities.

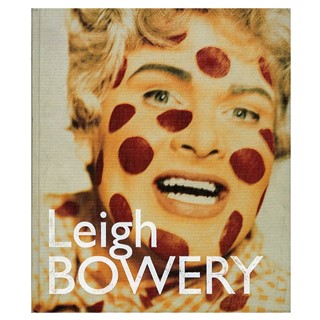

3. Leigh Bowery by Robert Violette (1998)

McQueen was endlessly fascinated with the Australian performer Leigh Bowery, an indomitable figure who reigned over London nightlife in the 1980s and early 1990s. In his early years, Bowery ushered in a new era of flamboyance that took seed alongside the New Romantic movement; later, he would become an art industry darling, posing for Lucian Freud alongside friend Sue Tilley. McQueen was by all accounts enamoured: one reminiscence by photographer A.M. Hanson of Bowery’s final performance at Freedom nightclub in 1994 – which involved a naked Bowery, singing about in Comme des Garçons, vomiting into the mouth of his wife Nicola Bateman – remembers the designer speechless, “agog”.

It is not difficult to see how their paths crossed; for Bowery, the body was a canvas for transgression, much like the clothing which McQueen would subsequently produce. And, though Bowery’s influence could be felt throughout McQueen’s career – not least in the will to shock – his most explicit ode to Bowery came in his A/W09 Horn of Plenty collection. There, models sported Bowery-esque blown-up red lips and wore clothing – in fabrics evocative of bin bags, or cling film – that posited the delights of turning trash to treasure, which Bowery did best.

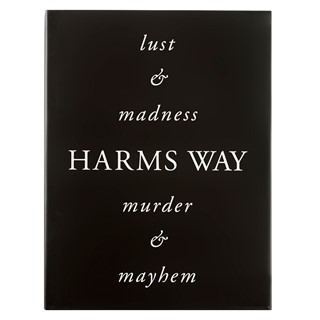

4. Harm’s Way: Lust & Madness, Murder & Mayhem by Joel Peter-Witkin (1994)

Such was McQueen’s knack for performance that his shows remain seared in the memory whether or not you personally attended. Still, few provoke such a visceral reaction as the finale of Voss (S/S01). The culmination of a show which explored the idea of confinement, set among the trappings of a mental asylum, fetish writer Michelle Ollie was revealed nude, reclining and covered in moths, hooked up to a breathing tube in a recreation of Joel Peter-Witkins’ photograph Sanatorium.

“There is for me in this situation a strange, terrible sense of being forced to view the events in rooms of asylums or places of torture,” Peter-Witkins said of the original photograph. “But most importantly, it is a depiction of an egoless being, a shaman in existence here and beyond.” The above book, Harms Way: Lust & Madness, Murder & Mayhem, was published by Witkin in 1994 and collects photographs of Victorian crime scenes and asylums sourced from the Burns Archive and the Kinsey Institute for Sex Research. “I think there is beauty in everything. What ‘normal’ people would perceive as ugly, I can usually see something of beauty in it,” McQueen would say of his fascination with the macabre.

5. The Birds of America; from original drawings by John James Audubon (1827–38)

“Birds in flight fascinate me... I’m inspired by a feather but also its colour, its graphics, its weightlessness and its engineering. It’s so elaborate. In fact I try and transpose the beauty of a bird to women,” McQueen once said. His fascination with birds began in his youth – he was a member of the Young Ornithologist Club. Isabella Blow, longtime friend, would say his clothing moved like the wings of a bird, and this animal and its plumage appeared again and again in his collections. For his Sarabande collection, S/S07, he looked at the illustrations of John James Audubon’s The Birds of America, which were then handpainted onto the collection. The paintings in the book itself – in its original incarnation, life-size – capture all known bird species in North America at the time, and toe the line between biological survey and artistic endeavour. McQueen knew this dichotomy well.

With thanks to the National Art Library. The full Alexander McQueen Research library can be found here.