On the Saturday evening of London Fashion Week, in the sombre, baroque space of Central Hall Westminster, Simone Rocha presented her Autumn/Winter 2023 collection. The Irish designer is lauded for her sense of theatricality and spectacle – guests at her shows dress opulently for the occasion, often head-to-toe in Simone Rocha – and this season was no different, with guests seated across two levels of the red-carpeted hall underneath a large dome; a sea of waxen pearls, shimmering sequins, delicate lace, bouncy tulle and chintzy florals. The venue, a Methodist church and conference centre previously host to suffragette meetings in 1914, was instead utilised by Rocha for its musical qualities; guests were treated to a haunting performance by Irish folk group Lankum, complete with a live set on the towering silver organ flanking the wall behind the band.

Drawing primarily on the traditions and rituals of Lughnasadh, the festival of harvest in Ireland, Rocha spoke backstage of an “earthiness” running through the collection. Alongside her signature, more glitzy approach to fashion – this season included crinkly gold ensembles, detachable sailor collars made of gems and beads, and baggy lace shirt and trouser combos – Rocha had stuffed dried raffia (which gave the illusion of straw) into the crevices of dresses, implying an overflowing and a simultaneous connection with the land. One of Rocha’s central references this season was Perry Ogden’s Pony Kids, the cult 1999 photo series capturing Dublin’s Traveller and Settled children with their ponies – now a rare classic in outsider documentary photography.

Ogden modelled in the show, appearing in a white shirt and a sparkling black top coat (a world away from the informality and grit of the characterful photo series that made his name). Elsewhere, models held macramé bags under arm like hay bales, while two knotted raffia dresses in pale yellow and black recalled the hooped raffia skirts of Simone Leigh’s powerful sculptures (Leigh was the first Black woman artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2022, and was dressed by Rocha for the opening). “I was thinking of the west of Ireland and being on the water. It’s really dry [there],” Rocha said of the show’s inspiration, in reference to the mix of sailor and farmyard motifs on display.

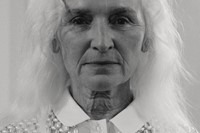

Rocha put actors on her runway this season, most of them Irish – like her – although they were difficult to differentiate between run-of-the-mill models. Rocha is a connoisseur of art and culture, having curated an exhibition of women artists in Scotland last year that mixed bigger names like Cindy Sherman and Louise Bourgeois with rising stars, and the same can be said of the designer’s taste in film. This season, the actors in the show were of cult fame; there was Samantha Morton of Synecdoche, New York (and her daughter Esmé Creed-Miles), Patrick Gibson of The OA, Aisling Franciosi of The Nightingale, Olwen Fouéré of The Northman and more (alongside big-name models like Karen Elson and Lily Cole).

“Simone narrates her life through her work, her relationship with Ireland and her roots, motherhood, family, and her take on the feminine and the masculine,” says Celestine Cooney, a stylist and a friend of Rocha’s, who attended the show in a strong khaki bomber-and-trouser men’s look from last season. “Wearing her clothes makes me feel like I could command an army on horseback and then attend La Bohème at the Royal Opera House in the same outfit that evening.” Francesca Hayward, principal dancer with the Royal Ballet – who attended the show in an all-white outfit and has previously collaborated with Rocha on a short film – says that when she wears the brand, she feels “powerfully feminine, wholly unique. I feel delicate and romantic but also very strong and fierce and like everyone should be scared of me.” Zola director Janicza Bravo explains that, while wearing Simone Rocha, she feels like a John Singer Sargent painting, or “like dessert before dinner”.

Last season, Rocha dabbled in menswear for the first time, with critics praising her soft, delicate approach to masculinity; there were bombers cascading with tulle, pearl-encrusted jackets, and bejewelled trench coats, with one male model’s face smeared in glitter and obscured by pale pink swathes of fabric. James Massiah, a south London poet and musician, believes Rocha is carving out new terrain with her menswear. “Simone does a great job of subverting norms, [with] the skirts, the frills, the long flowing coats,” he says. “I take great pleasure in challenging expectations in this regard, and she does too.”

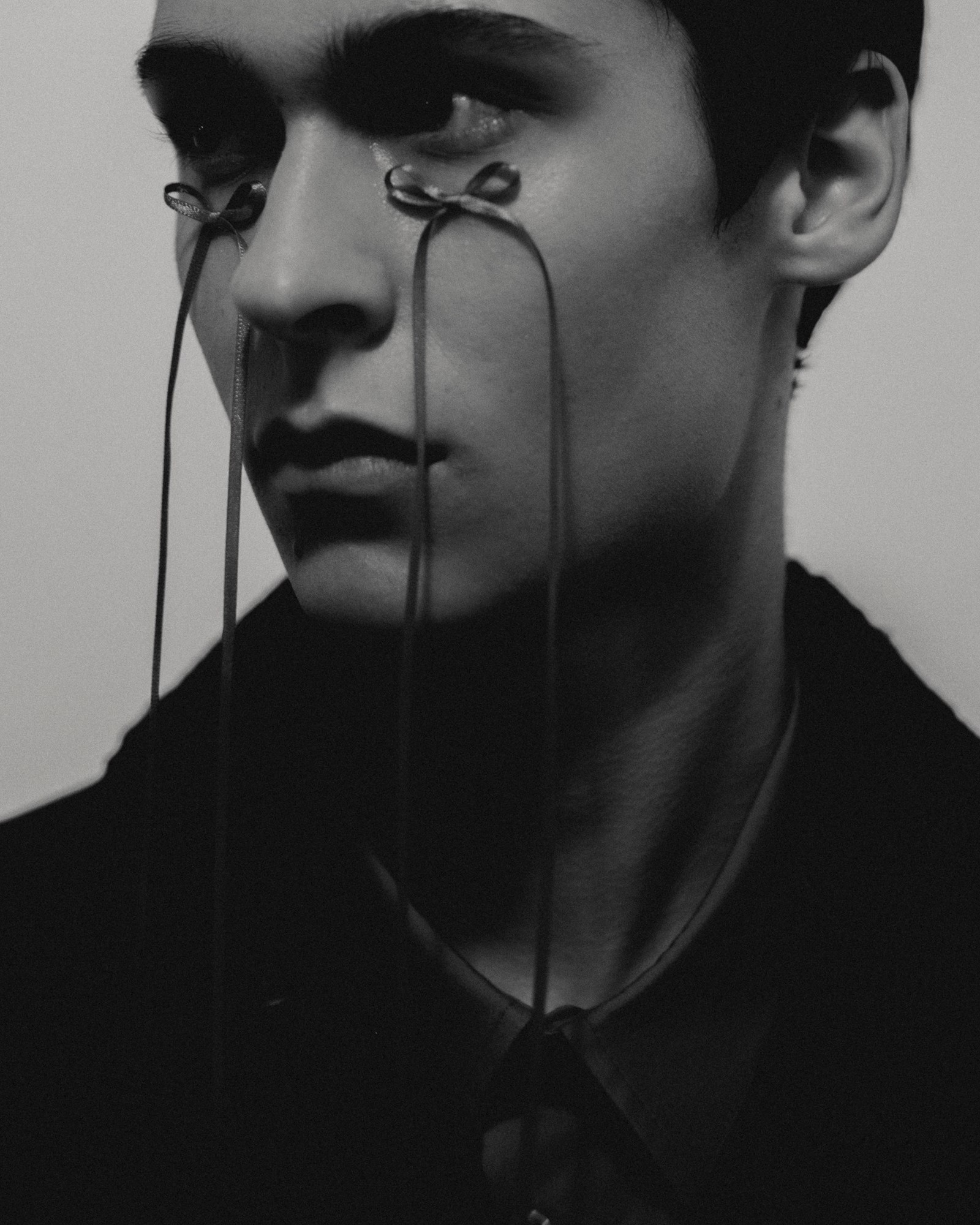

This season, Rocha’s men and women walked through Central Hall Westminster and into the light with tiny red and white ribbons tied in bows in red glued beneath their eyes, giving the illusion of tears and bloodshed. And with the ominous, primal sounds of Lankum’s concertina and uilleann pipes reverberating through the hall, it was difficult not to feel emotional. As in her previous shows, Rocha proved that fashion is about much more than just clothes; in weaving together the disparate threads of art, Irish tradition, music, and people – and lightly pushing against gendered codes of dressing – this was fashion as pure feeling.