To coincide with the launch of Garmento's third issue, Insiders speaks to the zine's editor and publisher Jeremy Lewis about his inspirations and motivations and whether postmodernism a license to borrow from the past without irony...

In the debut issue of Garmento, the semi-annual fashion zine out of New York, editor and publisher Jeremy Lewis poses a provocative question: “Is fashion having an American moment?” In the ensuing pages, he cogently and calmly presents his argument through profiles on American iconoclasts like Bonnie Cashin, Miguel Adrover and Matthew Ames. Extraordinarily researched and thoughtfully considered, Garmento is a refreshing antidote to the slick sameness and diminishing search for the new of much of fashion publishing, instead concentrating on making connections between the present and the not too-distant past, none so apparent as when he posted a side-by-side comparison of a coat from Phoebe Philo’s A/W13 Céline collection alongside an archive Geoffrey Beene piece which had WWD wondering “Is Phoebe Philo channeling Geoffrey Beene?”

And while he curates a beautiful selection of vintage advertising campaigns from Jil Sander, Donna Karan and Prada among others for the website, Lewis recently branched out to an appropriately old-fashioned form of communication with a series of live talks with some of menswear’s strongest hopes like Patrik Ervell and Tim Coppens at the Museum of Arts in Design in New York titled "Conversations in American Menswear." The new issue out this month intriguingly explores “outlying anomalies in fashion” featuring profiles on Hood by Air’s Shayne Oliver and a rare interview with the visionary Andre Walker.

What made you start up Garmento? What references did you have in creating the look and feel of it?

Charles Kleibacker, a curator I worked with in school, had passed away and I was frustrated about that. He had designed his own line in the 70s and retired in Ohio and he taught me how to really look at a garment not just for its craftsmanship or beauty but for the level of thought a designer puts into creating solutions within that garment. I felt like there were too many stories in fashion that weren't being told and that it couldn't be the sole responsibility of museums and academics to tell them. I had been dabbling in fashion writing and fashion editorial and so it made sense to make a zine to tell those stories. From the start, before I even found a name, I knew I wanted it to be on newsprint because I loved the idea of something being really cheap but still very precious and I loved the visual and tactile experience I got from flipping through old yellowed newspapers and magazines.

"I felt like there were too many stories in fashion that weren't being told and that it couldn't be the sole responsibility of museums and academics to tell them"

Garmento takes a considered, literate look at fashion, drawing connections between the past and present which seems at odds with a lot of fashion magazines today which focus on the new. Has making the zine changed the way you perceive and consume fashion?

Definitely. When you factor in all the clothes from the last century, or even the last millennium, and put it into context with what is happening now your perception has to adjust to compensate for that increase in scale and variety. I don’t really view the progression of fashion as a straight line like I used to, it’s more of a flat plane moving in all directions, and maybe there’s more activity in one direction than in others at any given season or period. But now I’m not even sure if fashion is the best way to engage new ideas about dress and clothes, the system is a bit too muddled. Has making the zine changed the way I consume? Probably. I’m a lot more conscious of what I buy because I do make a zine that presents certain attitudes that are vaguely polemical. If my actions contradict that I’d be a hypocrite. The first issue put a strong focus on clothes being made in the U.S. and I do make a conscious effort to buy goods that are American made, but I also shop at Uniqlo and that’s my reality. What I think is essential now is to simply be informed about what you consume and how it's being made and sold.

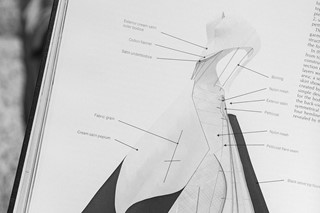

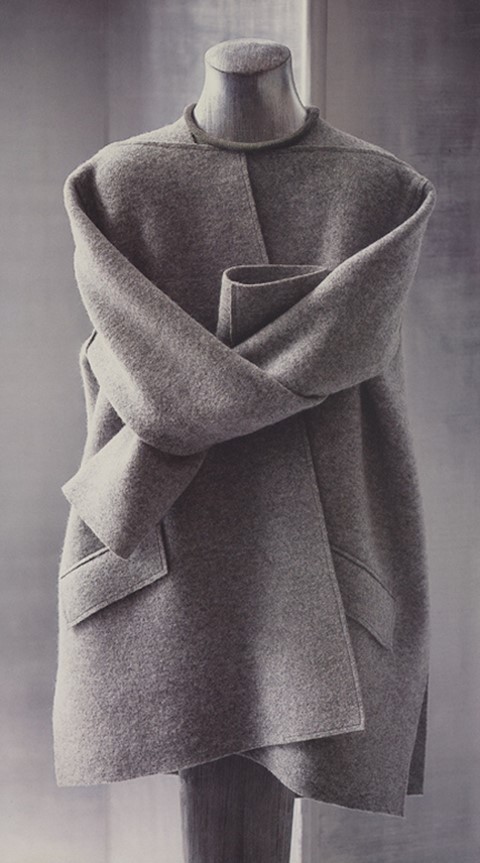

On your blog, you highlighted the similarities between a coat designed by Geoffrey Beene with a cape from Phoebe Philo’s AW13 collection for Céline – what is your take on this? Is postmodernism a license to borrow from the past without irony?

I loved it. When I was clicking through the Céline show on style.com and got to that look my heart stopped. It was a fashion moment for me. Beene was a true master and it was like a dream to see his work get some attention and love on that scale. But I was actually surprised there was no mention of it in the reviews because it’s a pretty well-known image and you can find it in almost every book on him. Now there’s this debate online and people are aggressively accusing the house of copying. Appropriating another designer’s work is, to me, a part of the evolution of design, and it’s not really new. You don’t think Chanel looked to Jean Patou? Or that Patou looked to Chanel? Or that Dior didn’t get his idea for the New Look from Charles James? It's like how a scientist wouldn't go about devising a new theory without investigating and understanding the theories and truths prior.

"Appropriating another designer’s work is, to me, a part of the evolution of design – you don’t think Chanel looked to Jean Patou? Or that Patou looked to Chanel?"

To me looking to other designers only becomes a problem when the idea that is being considered remains static. It cannot just be a copy, that’s just a waste and certainly when you are making a huge production on a catwalk that is broadcasted to thousands of people and you show a copy it really defeats the purpose. I think the excitement happens when that idea is advanced and the discussion is moved forward, and that’s exactly what Céline did. And honestly she didn’t really reference the coat per se, it was really the photo and the photo, with the arms tied, was more like a trompe-l’oeil effect on the runway than an actual facsimile of the object. And she took the seaming, the shape, the fabric, its ease, and turned it into a dress, and then another coat, and then back into another dress. And you know, there were other Beene-ism’s in the collection, like those Chinatown bag plaids, that juxtaposition of high and low fabrics, the cheap and the luxurious, the humor and wit of that is more Beene than the coat! There’s a lot of good stuff to explore in that collection than just that one look. What I really hope is that now people will go back and look at Beene’s work and give the man the praise he’s due. And maybe more designers in America will feel empowered to go back through their history and learn from it.

Who would you love to interview for the zine?

This is so hard to answer. There are a lot and I don’t want to give away any scoops. I would maybe need a time machine or a psychic medium to talk to the people I really want to. I’d love to talk to Halston circa 1978. I’d love to talk to Perry Ellis or Willi Smith circa 1985. To me they were all integral to fashion even though their contribution has been almost totally obliterated. It’s strange because there are people who knew them intimately and talked to them every day when they were alive but to me they are these untouchable legends and I think this distance is part of the problem with bringing their ideas and contributions to the fore. But it’s hard to remove that distance when they’re no longer here to speak for themselves. As far as living designers go, I’d love to talk to Stefano Pilati. I think he’s one of the most intriguing and complex designers to have come a long in a while.

Text by Kin Woo